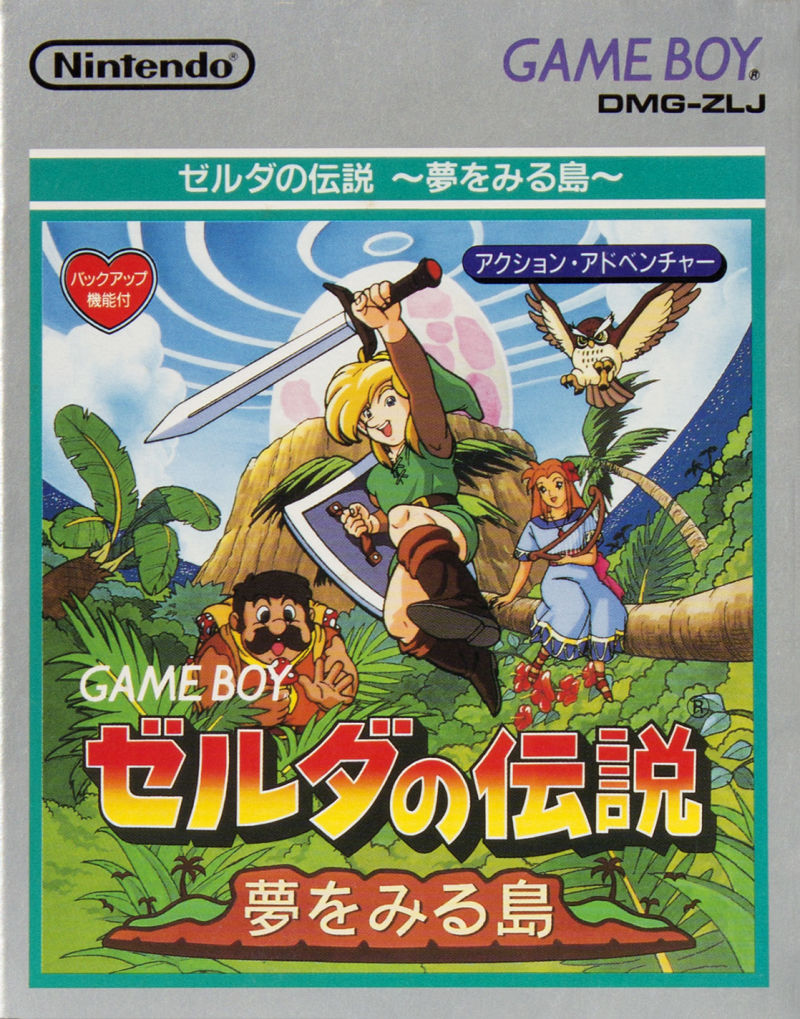

The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening

- Japanese release in June 1993

- North American release in August 1993

- Published by Nintendo

- Developed by Nintendo EAD

The Secret Best Zelda Game

When I was a young kid, I would devour the promotional pamphlets that came with every new game I got. I still remember getting a pamphlet from Ocean promoting The Untouchables on NES. I swear that a month doesn’t go by where I don’t reflect on how I thought The Untouchables on NES seemed so evocative to my nine year-old self.

Through one of those evocative promotional pamphlets and word-of-mouth, I learned of the existence of a Game Boy Zelda game. My young mind tried to imagine what kind of portable adventures Link would embark upon. This must have been in 1994, one year after the game came out. I wanted to have that game so much but I couldn’t find it at my local store. I’m from a northern region where it didn’t feel like we were outside of civilization but we only had one store selling games, Zellers. So if Zellers didn’t have it, it might as well have not existed at all. I then made it my mission in life to find the game. I mustered the courage to call the Nintendo hotline (my mom actually talked on the phone). They told us that if the game was gone from stores, I was out of luck. My friends all knew I was looking for the game and one day I was told of this older kid who had the game and wanted to sell it for twenty dollars. I was so happy but twenty dollars was a fortune! I didn’t have that kind of money. I was eight in 1994, no kid I knew had twenty dollars lying around. If I wanted that kind of money, a very serious discussion with my parents needed to happen at the dinner table. I was in third grade and I think I had never bought anything by myself before. My mom, always the cool parent, agreed to give me twenty dollars. I was given clear instructions on how to handle money in the schoolyard (keep it in your pocket, only give it to the kid who’s selling the game, etc.) and given a twenty dollar bill. I nervously met the older fifth grader, who promptly told me the game was for babies and he wanted to use the money to help pay for a Genesis. I don’t think there has ever been a more stereotypical Genesis kid in the history of the world. For the first time in my life, I paid for something by myself. I was so nervous for the rest of the day, looking at the game box and it’s beautiful simple cover: The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening. Was it fun? Was it good? When I first played it that evening at home, I realized it was essential.

The Special Relationship

My friends played Zelda games, but Link’s Awakening was my thing. A lot of friends had Zelda on NES, a lucky few had Zelda II with its sublime side-scrolling mechanics and everyone seemed to have A Link to the Past on Super Nintendo but nobody else I knew owned The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening. Only I knew of Koholint Island and the secret of its giant egg. Only I knew how to get past the bloody boss key puzzle of the second dungeon. To this day, Link’s Awakening feels like my Zelda game. Let me walk you through the beginning of my Zelda adventure.

The Best Introduction Ever Put on Game Boy

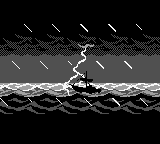

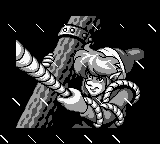

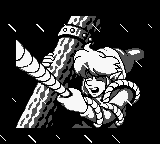

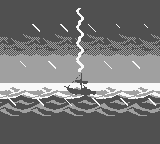

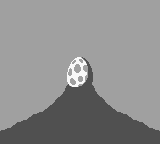

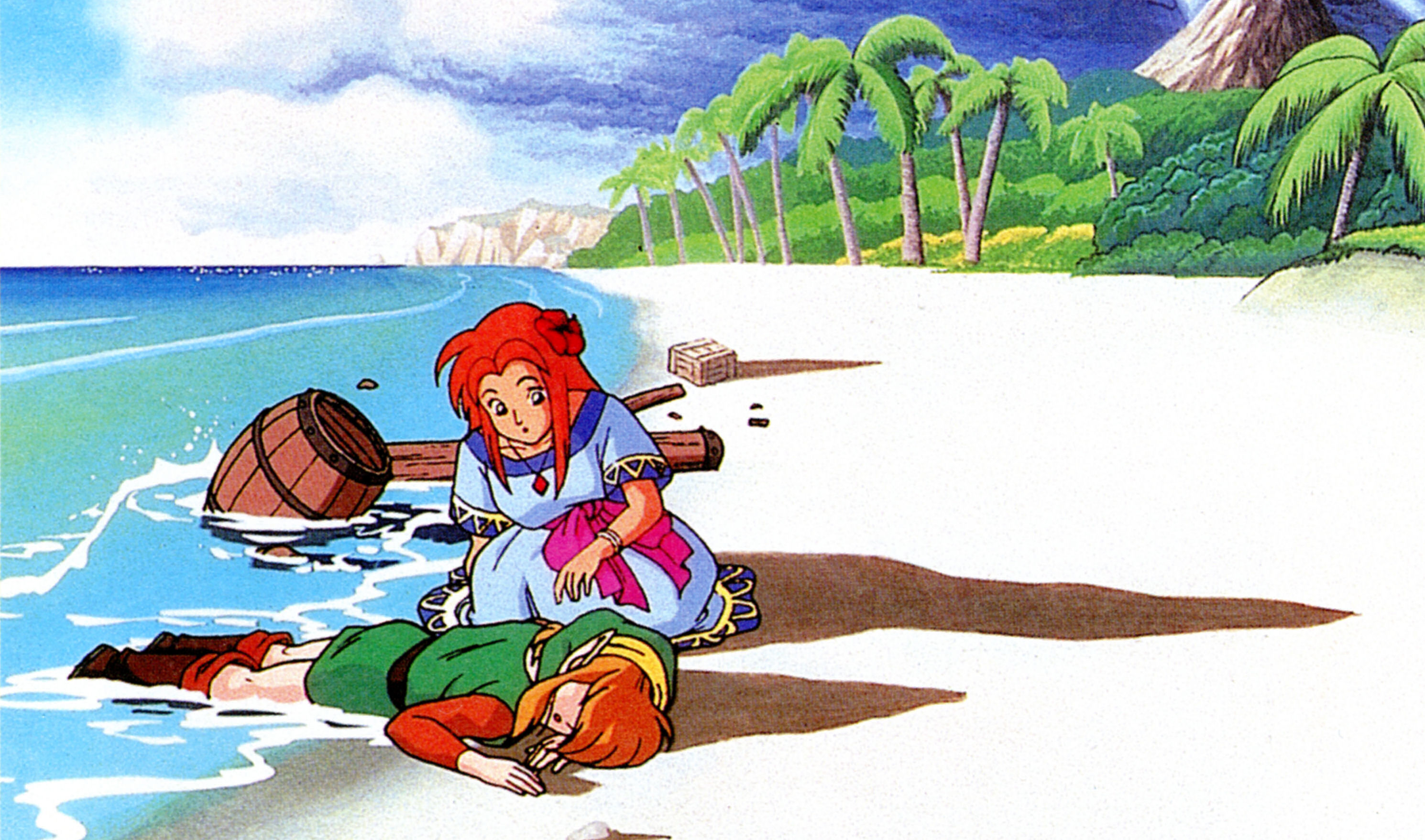

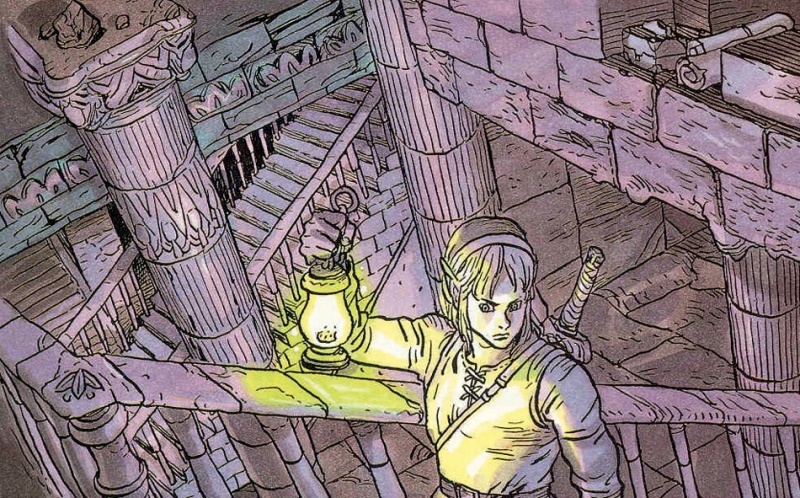

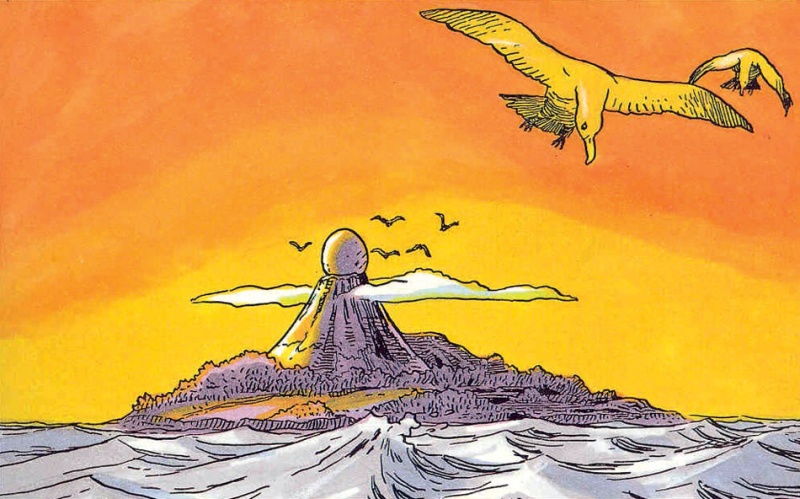

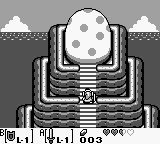

When you first turn it on, you’re immediately thrown into a storm, without any logos beforehand. Except for the mandatory descending Nintendo logo the console itself boots with. Fun fact, that logo is actually a copyright mechanism intended to prevent unlicensed games from playing on the console. After that small slice of software obscurantism hiding as a copyright claim, you’re immediately thrown into music that could not be clearer about the danger our hero is in. Link is riding on this frankly minuscule boat. Through a limited amount of scrolling elements, an alternating rain effect and only two screens, you get a clear picture of the severity of the storm and what is happening. Link is in trouble. The boat gets hit by lightning. Fade to white. The sound of waves hitting a beach. A girl looking like Zelda walks on the beach and finds Link washed ashore, clearly unconscious. Pan up to one of the craziest things you could ever imagine: an enormous egg sitting on top of a mountain. Cue logo and Zelda’s theme.

In exactly one minute, you are given a wonderful introduction to a story that will unfold in front of your eyes through hours of play. This is a masterclass in portable storytelling. No words, no undue length, full of emotion and mystery. Yoshiaki Koizumi, who was responsible for making the introductory sequence, knew exactly what he was doing.

The Shield

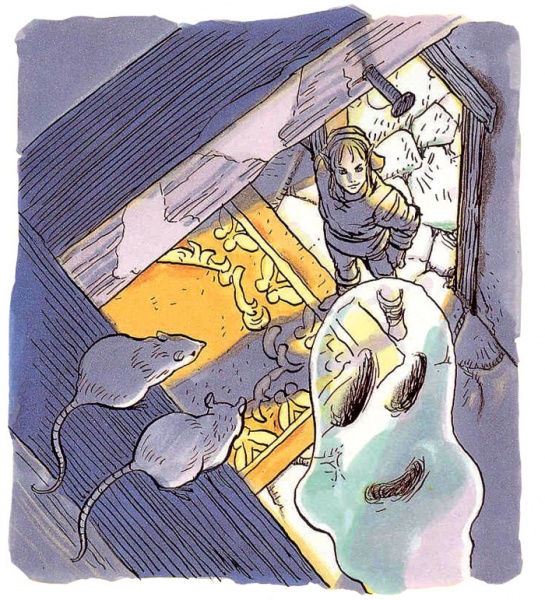

Link wakes up on Koholint island the night after a storm destroyed his little boat. He’s rescued by a family with a father conspicuously similar to Mario and a daughter similar to Princess Zelda. Link is given his shield and forced to go to the beach to see if more of his stuff didn’t wash up on the shore. You search and quickly see your sword but you can’t reach it! It’s blocked by spiky creatures. They don’t move. You would use your sword to dispose of them but getting your sword is exactly what you’re trying to do. You search for hours in the hope of finding another option. Then a stroke of luck. You realize you need to push a button to raise your shield and you can push the spiky enemies with your shield. It’s a completely different way to use the shield; the shield worked automatically in all the previous games. You finally get the sword and move on to the next puzzle after hearing about some mysterious stuff from an owl. You’re clearly in for a ride. There are multiple puzzles like the initial sword puzzle but I want to talk next about the most obtuse one in the whole game: obtaining the second dungeon boss key.

The Second Dungeon Boss Key Puzzle & Its Friends

When I got Link’s Awakening, I was around nine years old. I could read no English but had voraciously played both the first Zelda game on NES and A Link to the Past on Super Nintendo. I had seen and shortly played Zelda II: Adventure of Link at a friend’s house but really only played it when NESticle came out around 1998–2000. The only way my best friend and I got through our Zelda games was out of sheer will. You get to truly appreciate the value of visual cues when you cannot read any of the text. A great example is A Link to the Past’s map. While characters tell you where to go next, you can also see helpful numbers telling you what dungeon is next. So you can figure out where you should go next without reading anything. Now you only need to figure out how to open the door to the dungeon. How simple: the only thing you have to do is try every conceivable item in every spot to open the way! Here’s a very good example of how maddening the whole thing was.

To open the second dungeon of A Link to The Past you need to read the book of Mudora in front of the stone tablet in front of the entrance to the dungeon. It’s already hard enough to figure out for kids, imagine kids who can’t speak the language of the game. You have to figure out you can talk to an old man after finishing the first dungeon who will give you the Pegasus boots to run. You then need to dash with the Pegasus boots towards a bookshelf in a house in Kakariko village to make a book fall from the top of that bookshelf so you can pick it up and then use that otherwise useless book on the other side of the map on the stone tablet to decipher its text. That means Link starts praying and that somehow moves the statue that’s in your way. That took us maybe ten hours to figure out.

Without the benefit of a friend to bounce ideas with, there were even more situations where I was stuck in Link’s Awakening, like the second dungeon boss key I mentioned previously. I was stuck trying to get that key for months. Keep in mind, I had to use batteries to play the game and those weren’t exactly cheap. I had a ration of AAs and when I ran out, I had to persuade my parents to buy more. So every time I opened my Game Boy to play Zelda, I had to be very deliberate with my research. I vividly remember trying to play the game in my mind to figure out the puzzle because I had run through my quota of batteries.

With the help of the compass item which showed where treasures were on the map of the dungeons, I knew exactly which room this boss key was in. There was nothing else I could do to help me figure it out. I distinctly remember starting a new game twice to make sure I hadn’t forgotten something on the way to the second dungeon. Remember, replaying the game from scratch cost me AA batteries I had to ask my mother to buy. I had no luck with my restarts, I was stuck trying to figure out what the deal was with that bloody room. If you’re an anglophone, you can pick up the stone slab from a chest somewhere else in the dungeon which allows you to read the only clue on a goddamn stone tablet. To make matters worse, the stone tablet about this room’s puzzle is on the other side of the dungeon. I mean come on. It’s as if Nintendo’s EAD team made stone tablets on purpose to fuck up people who couldn’t read the language of their Zelda games. The clue in question?

First, defeat the imprisoned Pols Voice, Last, Stalfos. . .

Looking at forums online, it seems a lot of people who could read English had problems figuring it out as well especially since the clue mentions the enemies by their completely nonsensical but otherwise canonical names. What’s a Pols Voice and Stalfos anyway? That clue is germane with its weird sentence structure. If they had thought about it, there would have been the standard little jingle telling you what you’ve done is wrong after you killed all three enemies. Instead, you just get nothing. The first time, I got through the puzzle by sheer luck. It was only years later I realized there was a specific way to solve it; you have to kill the three enemies in a specific order, starting with the rabbit inside the blocks. Naturally, you push the blocks and kill the rabbit only after taking care of the other two enemies, meaning you always fail. Now that I’ve gotten this pain off my chest and I can go back to gushing over the game.

The Map

After getting the treasure from the second dungeon (the Power Bracelet which allows you to lift rocks), the overworld of the game opens up considerably. A Zelda title is only as good as its map, and here we have the smallest Zelda map ever. It’s small yes but it doesn’t feel cramped. Not every screen is essential to the game, there are little dead ends, weird nooks and crannies and unnecessary detours and shortcuts and a lot of it is set aside for the water rapids mini game and Richard’s castle. It feels much bigger than it is in reality. The one mixed bag is the mountain range. It’s only two screens tall, and the mountain is as wide as the whole map. You can only enter the mountain range from the middle and decide whether to go left or right; you thus end up on a very linear track to get to either dungeon 7 or 8. It’s the complete opposite of the labyrinthine Death Mountain of the previous games.

To help you navigate that map, you have a warp system. The Legend of Zelda and A Link to the Past both featured warp systems, but here you have simpler versions of both. You can use a specific song on the ocarina to warp at anytime like on SNES but this warp is a one-way trip to a single central destination. The other warp system is a bunch of glowing holes that transports you between all the portals you’ve previously used by shooting you in the air like a cannonball! Much cooler than the caverns of the first game. I used to just jump and jump and jump between the destinations, just for fun.

Focus on Dungeons or Overworld? Why Not Both!

I try to look at games in context, looking at when they were released, how popular they were initially, what their legacy is. With Link’s Awakening, I can’t escape comparison with Oracle of Ages & Oracle of Seasons, the 2001 sibling Game Boy Color games developed by Capcom of all people. Those Oracle games have truly great dungeons. The dungeons are very complex, with complicated but mechanically sound puzzles which are really rewarding to figure out. You’re having a blast in those dungeons. The multiple overworlds of the sibling games are not as successful. They have no useless side roads, no sense of exploration. You’re always feeling like you’re only going from point A to B. They’re filled with things to do, sure, but everything you do is very strictly regimented, everything is straight and narrow; they lack love and the sprinkling of little inconsequential details. You never just stumble into your next challenge by exploring.

Link’s Awakening strikes a perfect balance between the dungeons and the overworld with both being in perfect harmony with one another. The dungeons are true puzzles, the overworld is an exploration masterpiece. It’s a sight to behold, successfully pulled off because they let themselves experiment more; the tiny group of developers did not have Shigeru Miyamoto breathing down their neck. We’ll talk about this more in a bit.

We’ve discussed the beauty of the game’s world map, now let’s talk a bit about the dungeons. A Link to the Past, this game’s predecessor, did not feature many puzzles where the dungeon’s item was required to get through. They do exist but because you need the boss key to open the chest containing the item, the developers were limited in what they could do. Link’s Awakening got rid of the need to have the boss key to get the dungeon’s item. Now, dungeons are basically separated in two parts by puzzles you solve to get to the item and then by backtracking to areas you could not solve without the dungeons’ item. With that small change of the dungeons’ rules, they managed to radically transform how dungeons operate, making them much more complex and fun. It’s a transformation that’s still the basis of Zelda’s dungeon design to this day. If you want to know more about the genius of Link’s Awakening’s dungeons, Game Maker’s Toolkit has an awesome video series about it. Look it up.

With their great map design and their refinement of dungeon design, Nintendo EAD pulled a masterful subterfuge. In Link’s Awakening you’re always led along a path; it just doesn’t feel that way because you’re always given enough freedom to find that path on your own. You have to figure out what the path is and what little disparate branches you need to connect together. For example, at one point you’re leading a ghost back to his home and you’re not told exactly what to do next. When you have multiple rooms you can explore in a dungeon, you’re never told in what order to tackle them. With all future Zelda titles, the path would get narrower and narrower, the directives more and more direct until we got Skyward Sword which was decried for its absurd lack of freedom. It all started with Link’s Awakening where it was just right.

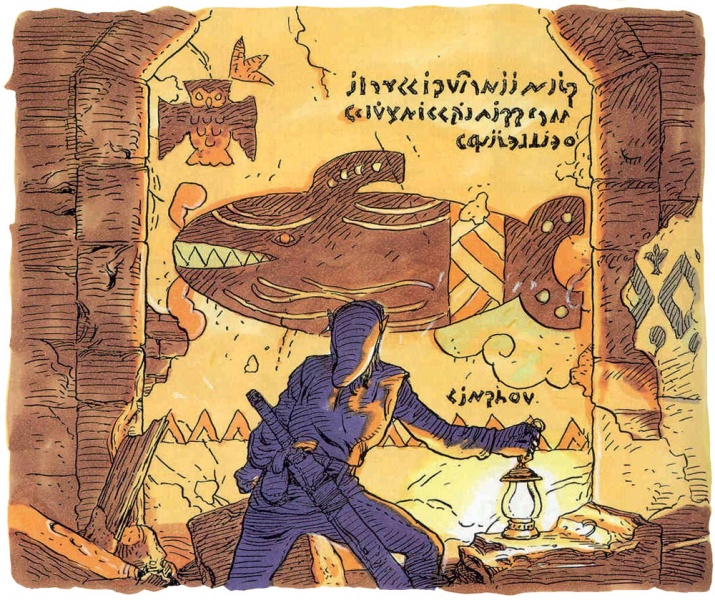

Influences Are the Fuel of Mystery

Through multiple interviews, Takashi Tezuka, the director of the game, has talked about what happened to make The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening. The game was made as a side project, worked on late in the evening when Miyamoto and the other bosses had gone home. Even though the trio of Tezuka Takashi, Nakago Toshihiko and Shigeru Miyamoto were seen as a power team within Nintendo, the junior members of that alliance appreciated not having the demanding Miyamoto around. See for yourself this excerpt of an Iwata Asks:

Iwata: Tezuka-san and Nakago-san, you two, along with Miyamoto-san were known as the “Golden Triangle,” or the “Kansai Manzai (comedy) Trio.” And with Miyamoto-san as the central creator, you developed the original The Legend of Zelda game while you were working on the first Super Mario Bros. But his involvement with The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening, the first handheld Zelda game, wasn’t that extensive, was it?

Tezuka: No.

That no is as much comment as we can expect from a Nintendo employee regarding Miyamoto’s management style. It and the rest of the interview are very clear, however: Miyamoto’s great at making your work better but he’s a hard ass. If you can work on a project without his constant involvement, you’ll have an easier time. Which they seem to have had: Link’s Awakening oozes fun and a laid-back attitude. Tezuka also wanted a Twin Peaks vibe from the world of the game. I know it sounds crazy, those two things couldn’t be more different. What he meant was a small town with few characters but all of those characters are somehow really off-key and strange. He certainly achieved that! A great example is Tarin, the father of the girl who first sees Link on the beach. He is a clear Mario analogue with his big round nose and cheeky attitude. He gives you your shield and next time you see him, he’s been turned into an aggravating raccoon that stops your progression until you transform him back because he ate a weird mushroom. A weird reflexion on the madness of Mario games. I guess it’s like Twin Peaks all right. I could go on about weirder situations, but there’s just too many. Helping Richard with his leaf problem, making sense of the owl’s weird proclamations, meeting the fish that dances for money.

Console Quality

At this point I’ve talked about two elements related to the start of the game in detail: The shield’s use to get the sword and the second dungeon boss key. The rest of the game I want to cover in terms of how it is so often described: as a console-quality game on a portable system.

It would be easy to say Link’s Awakening is a console-quality game on a portable console and to leave it at that. There’s just one problem. There is no such thing as console quality. For the sake of argument, let’s say the console we intend when we say console quality is the NES. Seems reasonable. What is console quality? Super Mario Bros. 3? Zombie Nation? Utsurun Desu?

My point is that a console is not a monolithic block. If it were, this website would not exist. Games are made by developers of different talents and even more important, under different constraints. Some developers might have a very limited amount of time to make a game, while others are afforded a lot of time to research and refine ideas. On Game Boy, this trend is painfully clear: a lot of games clearly had short deadlines and uninterested developers.

To circle back to Zelda, it is clear as day that the team at Nintendo EAD spent as much effort to make Link’s Awakening shine as they did A Link to the Past. The game is smaller, it has fewer dungeons. They obviously spent less time on the game because of that. But the refinements are there, the passion is there from start to finish. For Link’s Awakening, the developers clearly wanted to make a game as complex as anything available. Contrast with Super Mario Land, which is clearly taking inspiration from Super Mario Bros. when Super Mario Bros. 3 was being developed internally at Nintendo. They went back to a simpler, older game instead of trying to emulate the new hotness. For Link’s Awakening, they instead introduced newer concepts, building on the design work in A Link to the Past on Super Nintendo in lieu of perhaps trying to put the first NES game on Game Boy. The Roc’s Feather, which allows you to jump, is the best example. There is no such a thing as a jump button in A Link to the Past. They implemented the jumping ability cleverly, making it a clear evolution of what was seen on Super Nintendo. For Link’s Awakening they wisely moved forward, not back. Music-wise, gameplay-wise, story-wise.

Colour? We Don’t Talk About Colour!

In 1998 Nintendo rereleased the game as The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening DX. It’s a black cart which means it can still be played on an original Game Boy but has specific colour palettes if played on a Game Boy Color. It also changes a lot of little details. I’ve chosen to talk about it later. It deserves its own article.

Conclusion

These days, I can’t separate the intent of the developers from The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening. But when I was a kid, all I saw was an island in front of me ripe for exploration and filled with quirky off-key people. I sometimes long for that feeling of exploration and discovery coming from a 2½ inch screen.

If you’ve never played Link’s Awakening, I envy you. When you do play it, you’ll have a wonderful time. It’s essential.