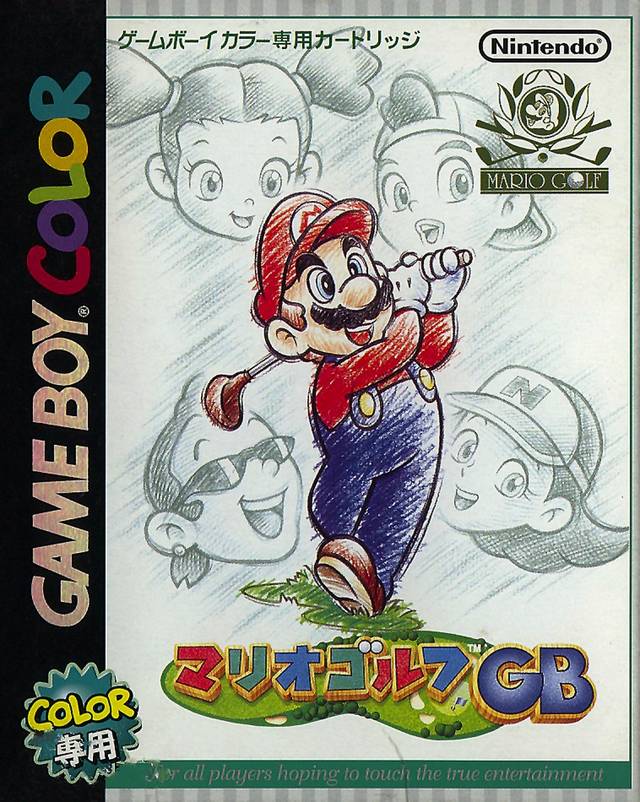

Mario Golf

- Japanese release in August 1999

- European release in October 1999

- North American release in October 1999

- North American release in 1999

- Developed by Camelot Software Planning

Baby Mario Golf

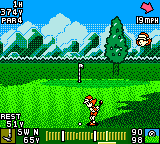

Sometimes, it doesn’t take much to push a genre in an exciting new direction. Case in point: Mario Golf. The game is a competent game of electronic golf, sure, but it succeeds because it sprinkles just the right amount of RPG mechanics to make it feel fresh and exciting. It has a little bit of a story. It has a little bit of a leveling system. It has a little bit of a map to walk around. It’s still mostly a golf game. Add those all up and you equal an essential game.

Modern Concessions

Mario Golf is just a good game of old-fashioned golf with an RPG of sorts added in. I’m well aware that this might sound totally mundane. Today, RPG mechanics are everywhere. Mario Golf eschews this modern way those mechanics are used everywhere and simply wraps its package in the tropes of a classic Japanese RPG, implementing one the same way games in the ’90s did. It directs your experience and gives you incentives to keep playing.

The contrast of what adding RPG mechanics to a game concept meant in 1999 versus what it means in 2018 is galling. They’re so ubiquitous we don’t even call them RPG mechanics anymore. They’re called unlockables, or a progression system or something else. And even if those mechanics don’t always affect the underlying number-crunching of the game, they often change your appearance or unlock stuff and they’re often used to nickel-and-dime players. Modern games will use old-fashioned RPG mechanics, but they’ll limit player progression in nefarious ways. This is meant to frustrate the player enough that it makes sense for them to buy shortcuts to rewards with real money, or turn to straight-up gambling inside those games to receive rewards. Not every game is guilty of it; a game like Luigi’s Mansion: Dark Moon is using the patterns of an RPG just like Mario Golf did. Game developers have used the frustrating parts of an RPG, namely slow progression and frustrating gates with specific requirements to get players to spend money to bypass them. We’re living in a bizarro world where only the bad design in Dragon Quest is copied! This makes me sick to my stomach. Mario Golf is such a nice respite from this insidious coopting of our natural addiction to filling up progress bars that it might as well have come from another planet, a planet where they also have golf and Mario.

Camelot’s Intentions

I think Camelot was trying to keep you more engaged than when playing other golf games. Golf games usually feature a main menu that allows you to select exactly what you want to do. It’s perfectly reasonable as a way to present a golf game, but it divorces the menu from the game. The menu is not a part of the game, it gives you access to the game.

Mario Golf on N64 tries its best to make its menu fun.

Mario Golf on N64 tries its best to make its menu fun. Most golf games instead tried to look serious and ended up drab.

Most golf games instead tried to look serious and ended up drab.Mario Golf, by having you walk around clubhouses and courses like in an RPG instead of focusing on a menu allows you to lose yourself in its golf-obsessed world. Characters will mention golfing methods, talk about why they love golf, etc. Mario Golf wants to make golf interesting for players who might not be interested in golf otherwise. The game even has a dictionary you can read if you don’t understand what people are talking about. I actually learned stuff in there. The Dictionary.

The Dictionary.

This fascination with teaching players the arcana of golf makes the Game Boy Color game much more memorable than its N64 forebear. Even though the N64 game is a much more competent, complex golf game, the Game Boy Color game is the memorable one because it’s so different from the regular experience of playing a golf video game. You might play a special challenge, like hitting a specific mark in one shot. You might want to play a full 18-hole. You might go for a match game. Those are all things you can do in other golf games, but here you get to talk to people and ask them to do that. Characters make fun of your poor golfing abilities, or revere you for your wins. Your trophies are displayed in a room in the Marion clubhouse, your kind of home base. You can go in the change rooms and chat with people there. The champions of the game’s first four courses sit together in an executive lounge and bemoan their loss at your hands after you’ve beaten them. You don’t get that from Lee Carvallo’s Putting Challenge.

You’re doing the same things as all the other golf games, but you’re doing them by walking around. I think the RPG walking around was actually implemented later on during development; you get a menu when you continue a game that gives you access to the same things as going around talking to people. Strangely, access to the menu disappears once you start a game. You have to completely exit your save game to see it again. It’s rare to see a game duplicating functionality. This leads me to think they might not have intended to have an RPG-lite in there until late during development. I’m not so sure, though. The Nintendo 64 Mario Golf game has a big focus on unlocking characters by beating them in match games but it does all of that through menus. I think they wanted some type of game progression and put what they had the time to do on the N64 version. They then refined their ideas further on GBC because they could spend the time with the Game Boy Color game. Ultimately, this unique character progression, just like the unique display technology of Toy Story Racer could only happen on Game Boy Color. The enormous market for Game Boy Color games coupled with easy-ish development on the console meant that experimental new ideas could be iterated on. The developers at Camelot had time to develop new ideas on top of the golf game they were already making.

One such new idea was experience points for your player character. You improve your character for completing tasks which gives you a nice incentive to keep going. Once you gain a level, you can see that the game uses a surprisingly deep statistics system for your characters. You get a point after every level that you can spend on four statistics: Drive, Height, Shot, and Meet Area & Control. You have to juggle your stats, since every level-up will slowly decay the other stats. And since only your hitting range is a stat that can always grow, leveling becomes this balancing act between putting points in drive to hit farther while also not forgetting to put points to keep the quality of your hits manageable. I usually hate those systems, since they mean you can absolutely wreck your character and have to start your game all over again, but I’m OK with this system because the developers at Camelot honoured Nintendo’s attention to detail: the way the system is displayed means you can easily understand what is happening. You cannot fail to understand how it works too late to steer your stats right.

So when you face Mario at the end of the game, his stats are impressive but you’ve spent the whole game building your character for that very moment. You will indeed spend the game thinking about your inevitable golf match of the century with Mario because everybody and their mother reveres Mario as the greatest golfer that ever lived in the world of Mario Golf. Keep in mind, you don’t play as a character from the Mario family. Instead you get to choose one of four very generic characters to play as. But the Mario characters do exist, they’re just the golf gods of this universe, with Mario as a kind of golfing Zeus.

Nine-Hole Version

I’ve slightly addressed its development already, but I have to mention that there’s no escaping this game is the junior version of Mario Golf on N64. It was released a couple of months afterwards, and was obviously in development concurrently with its big brother. Since it features mostly the same developers as the N64 title, I can definitely imagine them working on the N64 game and turning around to plan the Game Boy Color title in-between tasks. The game was mostly developed by Camelot, a company known for the Shining Force series on Sega consoles but who turned 180 degrees with these two projects and became Nintendo’s exclusive Tennis and Golf third-party developer to this day. They also developed the Golden Sun games.

So the game is very much a third-party game, with only four Nintendo employees in the credits of the game. Shigeru Miyamoto, which was very much only a supervisor by 1999, Yusuke Nakano and Yoichi Kotabe, who seemed to have been there to make sure the Mario characters stay on model, and finally Hiroshi Yamauchi, my favourite bespectacled CEO as the inevitable executive producer. The rest of the team is all made up of Camelot employees, with the director of Mario Golf being Yasuhiro Taguchi. He is one of the four supervisors on the N64 Mario Golf title, which seems to have been a more hands-off position for Nintendo overseers. He is the only Camelot employee of the supervisors, which I guess makes sense since both projects shared the same staff which probably required a lot of coordination on his part. Fun fact: the composer of Mario Golf on Game Boy Color ultimately became the Dark Souls I & II composer! Everybody’s gotta start somewhere.

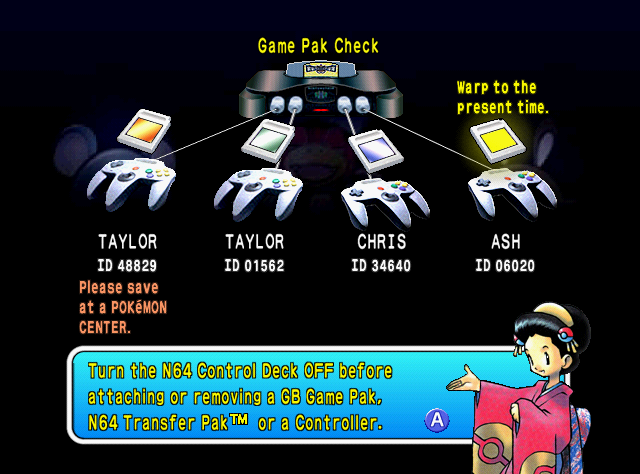

Transfer Pak

Another reason Taguchi was a supervisor on the N64 title might be their connectivity. Both Mario Golf games can connect to one another using the N64 Transfer Pak. The Transfer Pak initially came bundled with Pokémon Stadium and connects to the bottom of an N64 controller. It allows data to be exchanged between a N64 and Game Boy cartridge. Its main appeal was as a way to bring your Pokémon teams over to Pokémon Stadium and battle other players who also connected their Pokémon cartridge with a Transfer Pak on their controller.

Keep in mind that even though the Transfer Pak looks bulky, it does not include any Game Boy hardware; it is merely a passthrough connector. It cannot play Game Boy titles like the Super Game Boy and Game Boy Player can. People get confused (and I was confused when I was a kid) because Pokémon Stadium and Pokémon Stadium 2 can read a save game from a Pokémon cartridge and start an N64 emulator to play Pokémon Red, Blue or Yellow versions (and for Stadium 2, Gold, Silver, and Crystal). It does that by using a custom-built rom housed within the N64 cartridge. It then pushes your save back down to your cartridge connected in the controller when you save.

Mario Golf allows you to bring your character to the N64 version when connected. And I mean exactly that. It does not unlock a playable version of your character, it brings your saved character with their stats and given name. People tend to get confused and not understand why the characters disappear if you reset your N64. That’s because you are intended to bring your character back down to your Game Boy Color cartridge and receive experience points for what you did in the N64 version, and repeat the process the next time you want to play with your character on the N64. It all sounds interesting, but I haven’t tested it myself and have only read about it online. I did watch a sketchy video from 2008 about it on YouTube, though. Deep research.

Mobile Golf

Nobody seems to know about it, but Mario Golf on Game Boy Color has a sequel. I’m not talking about Mario Golf: Advance Tour on Game Boy Advance. I’m talking about Mobile Golf, the 2001 Japan exclusive sequel that was meant to be used with the Mobile Game Boy Adapter. The adapter was released in January 2001 in Japan and allowed a Game Boy Color to connect to certain Japanese cell phones through the link port. It obviously came out very late in the Game Boy Color’s life and was not very popular even though it was compatible with some early GBA titles. Its main appeal was to be used in conjunction with Pokémon: Crystal Version, which allowed players to battle one another over the internet. In 2001!

Mobile Golf’s main appeal is its Mobile Adapter functionality. It uses the same engine and overall structure as Mario Golf. I wouldn’t even mention it, but it has different golf courses from the previous game. Since it was only released in Japan, it is all in Japanese, and features very little in terms of improvement I can’t recommend it as an essential title. It’s an interesting footnote, and I guess I’ll talk more about the Mobile Game Boy Adapter when I tackle Pokémon Crystal. Mobile Golf

Mobile Golf

Kenji Miki Invented Everything

The last thing I want to talk about before I conclude is Kenji Miki. You see, golf video games truly start with Kenji Miki. He’s the designer of the original Golf on NES, the first modern golf game. Before him, golf games are unrecognizable as what we now know as a typical golf game because all subsequent golf games got their inspiration from Miki: his design for Golf invented the power & accuracy bar. Pouchy Torchbearer.

Pouchy Torchbearer.

You know instinctively what I’m talking about if you’ve ever played a golf game. The bar with a pointer that goes to maximum strength and comes back to a small sweet zone that controls accuracy which you both need to hit as precisely as possible. That thing, that’s a Nintendo invention. A Kenji Miki invention to be exact. Nowadays, people call it the three-click system. The story of its invention is a bit more complicated than what I just said though, with three games coming up with the same overall control scheme in 1984. Jeremy Parish goes into more details on those three games with his Golf video of NES Works. But Miki’s Golf is undeniably the most influential of the three because of its popularity. It’s also the most influential because it includes all the little traits we associate with a golf game. The view behind the golfer, the map of the field, the wind indicators, all of what makes a golf game a golf game is there from the get-go on Famicom. I can think of one major golfing concept added after Golf: hitting your ball on a different spot by holding a D-Pad direction during the power bar sequence. Aside from that one thing, Kenji Miki single-handedly created the golf game genre. Go play Golf on NES and you’ll see what I mean. It has no modern accommodations like automatic golf club selection and hit distance markers, but the gameplay is basically the same as the latest and greatest PGA golf game. Those accommodations are very important, don’t get me wrong; they’re the reason a golf game is not a frustrating ordeal like NES Golf. As time went on and golf games became more and more capable, the guesswork needed on your part was constantly diminished. They empowered you to strictly focus on delivering the correct shot, instead of calculating everything in your head. Let’s look at Mario Golf whenever you don’t want to hit at full strength for a good example. You are forced to stop and figure out whether you need to hit at a third the strength or a fourth the strength. You do that by looking at the distance between where you’re going to land at full strength and where you want to go. Golf Story, a 2017 Switch game that’s basically a big homage to Mario Golf, allows you to adjust your distance and will match your marker on the map with a power bar marker to show you when to press during your swing. This little improvement, and many others, made golf games much faster to play, turning them into snappy gameplay sequences.

Miki didn’t rest on his laurels; he did work on making golf games better. He was a supervisor on almost all Nintendo Golf games until he left the company in 2004. All golf games except this one, Mario Golf on Game Boy Color. So he was party to most of the improvements that came to golf games. Except the RPG conceit added by Camelot.

Conclusion

Mario Golf is great because even people who have no interest in golf can find something to enjoy. Nintendo and Camelot did that by building a two-pronged approach to golf. They first gave the game a strong concept that aped one of Nintendo’s strongest success: Mario Kart. A racing game with all the Mario crew became a golf game with the Mario crew. To accompany this proven idea they built a pick-up-and-play golf game for both of Nintendo’s consoles. They also had the wonderful idea to add RPG mechanics to the Game Boy Color version. It’s a great concept, which has now been reinvented with the very involved career modes of sports games like the NBA 2K series. In a sense, Mario Golf is to NBA 2K18 what a cave painting is to Renoir’s Déjeuner des canotiers.

This article was first published on the .

This article was last modified on the .