- North American release in April 2000

- Japanese release in April 2000

- European release in May 2000

- Brazilian release in 2000

- Developed by TOSE

Portable Espionage Action

I’ve spent my whole formative years watching the disappointing sequels to ’80s movies without having seen the first one.

- I’ve seen Ghostbusters 2 before the first one.

- Alien 3 was my first Alien movie.

- Same thing for Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, although that’s the best one.

- Robocop 2 was my introduction to the best cop in Detroit.

- My first Superman was Superman IV.

- City Slickers II: The Legend of Curly’s Gold was my first Billy Crystal movie.

- I only ever saw Coccoon: The Return, never the original.

- I managed to see Disney’s nightmarish Return to Oz before I saw the classic Judy Garland movie.

- Bill and Ted 2 was the only one of the two I’d seen until I saw the first one much later.

- I loved the craziness and meta references of Gremlins 2 without the need to see the original.

- Finally, like most of my friends I saw Spaceballs before I saw any Star Wars movie. I have to admit that the transformation of Spaceball One into Mega Maid was more impressive to me than any special effects in the first three Star Wars.

Which brings us to Metal Gear: Ghost Babel. I played the Game Boy Color game before I ever touched the PlayStation classic. Once again I enjoyed the follow-up first.

Before we move on, we need to clarify nomenclature. Upon its release outside Japan, the Game Boy Color title discussed here was called Metal Gear Solid. That being also the name of the 1998 PlayStation game, it would be unwieldy to constantly have to explain which of the two games I’m talking about. For this reason, I will refer to the Game Boy Color title by its original Japanese name instead: Metal Gear: Ghost Babel. It’s a nice name and a reference to the Game Boy. MG: GB. Get it?

Excitement

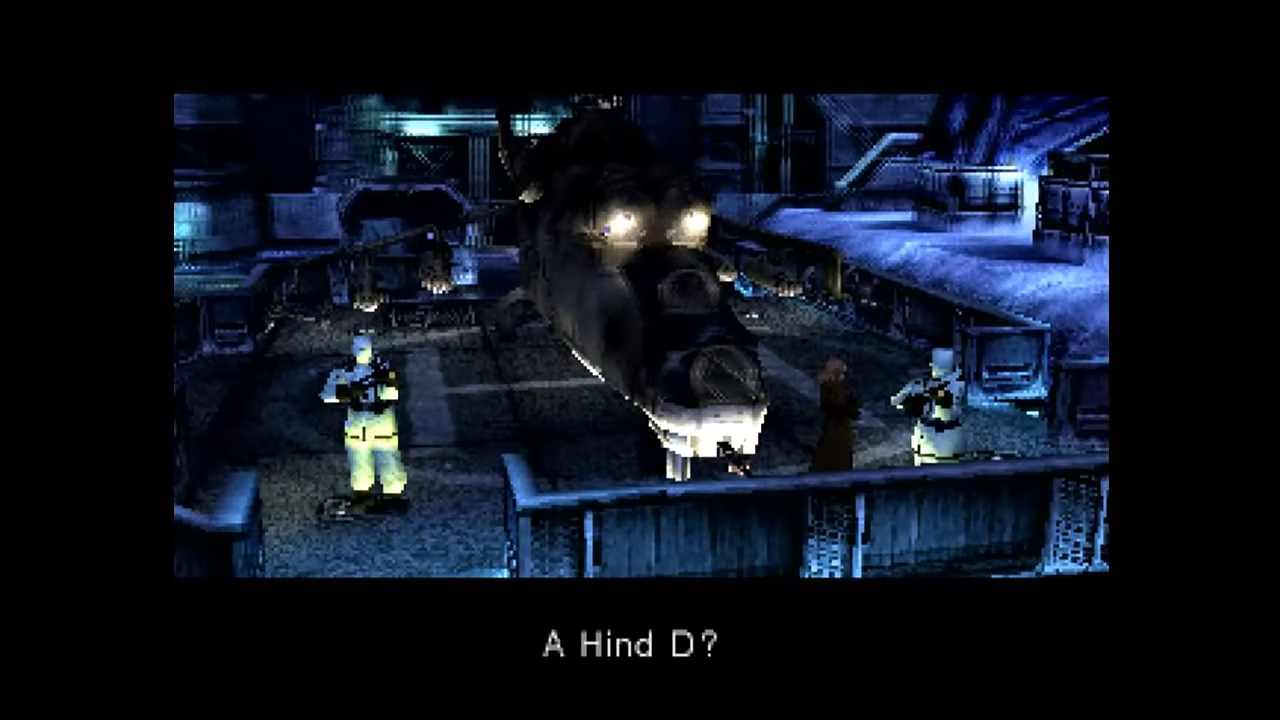

Back in the late ’90s I did not have a PlayStation but still wanted to play Metal Gear Solid. I was supremely interested; there was this video game that was supposedly as good as a movie! Of course, I had no idea back then that this was all marketing. Metal Gear Solid pretends to be a movie but is nothing like the serious films it tries to replicate. Hideo Kojima desperately wanted to make a game structured like a serious spy thriller, but he made soapy anime. Metal Gear Solid and the rest of Kojima’s games are beloved in large part because of this dual identity. Back then I only knew Metal Gear Solid was cool and I wanted to play it. A Hind D?

A Hind D?

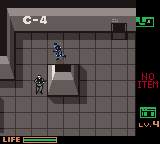

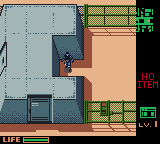

When Konami announced they were making a Metal Gear game for Game Boy Color, I was immediately interested. Initial images were very promising:

The people at Konami were not proposing strange gameplay mechanics that had very little to do with Metal Gear Solid. Many franchises coming to Game Boy would severely change their gameplay to fit the confines of the small console. Ultima, Turok, Resident Evil, Perfect Dark. Those are all franchises that drastically changed the gameplay for which they were known when they came to Game Boy. But here they were making a legitimate Metal Gear title. It even featured the radar system in the top right corner of the screen. That thing is really small, but you do use it all the time!

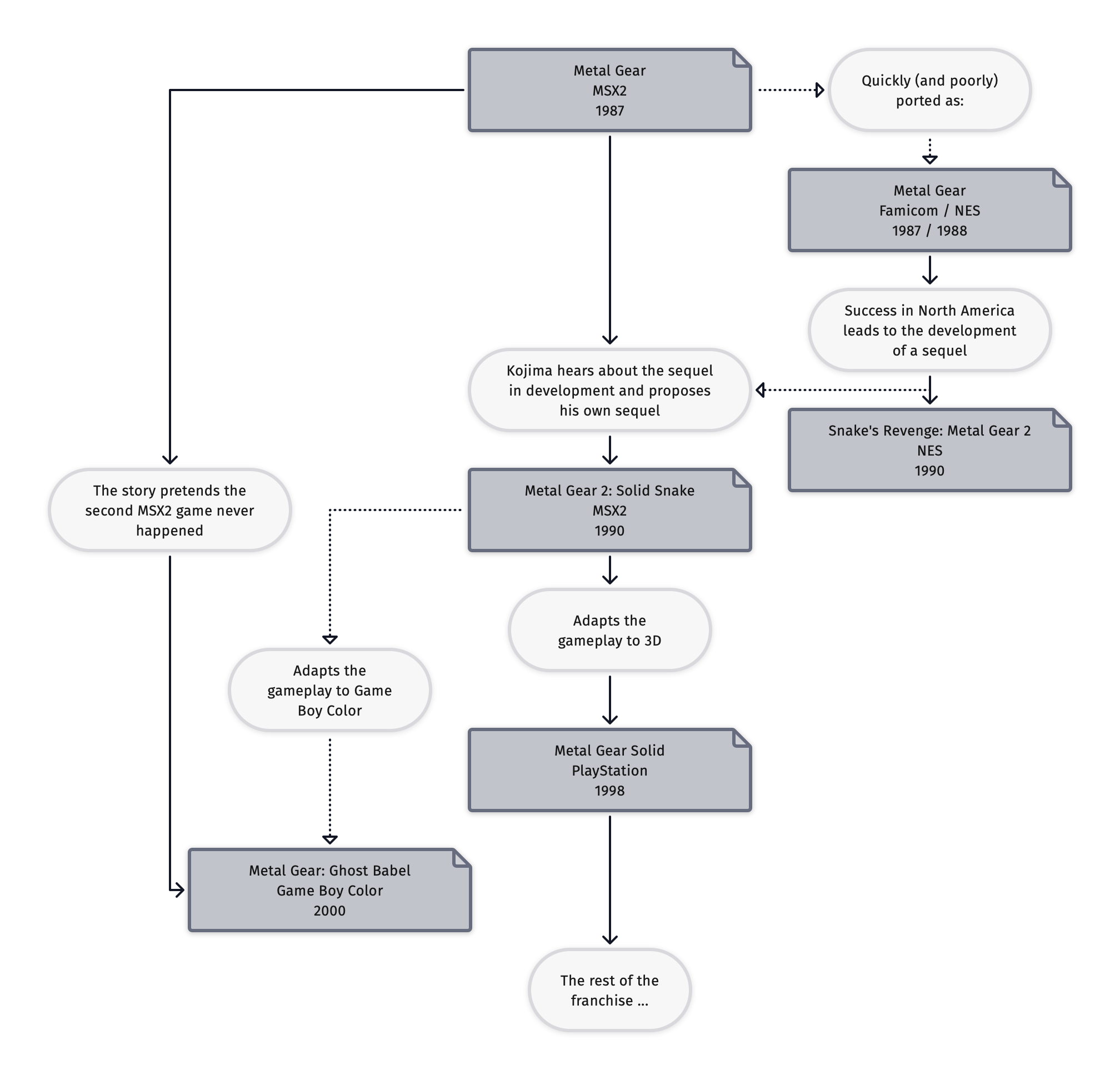

It also told its story through cutscenes, and to help you understand the convoluted way Metal Gear: Ghost Babel fits with the other games, I made a chart that covers the games’ story and development relationships.

When the game came out in March 2000, I have to remind you I pirated the game. In 2000, GBC emulators were good enough to play new releases as soon as someone dumped the ROM online. There were some games that did not work properly back then, which I talked about in my Toy Story Racer article. I even already told the story of my experience with Metal Gear: Ghost Babel. Let me tell it again. The first elevator of the game, encountered on the fourth mission, failed to move me to the next section of the facility. The second I pressed the elevator’s button, I was stuck in that elevator forever. In technical terms, I was softlocked. I could still move Solid Snake within the elevator, but I could never leave. I do not know if it was a bug or a voluntary anti-piracy measure. It would appear that the game indeed has code to lock up emulators on the title screen and I wouldn’t put it past the developers at TOSE to include piracy counter-measures later in the game. I’m not competent enough to test my theory, but keep in mind that modern emulators are now indistinguishable from real hardware. No anti-piracy code can get triggered anymore.

It was very frustrating to hit a wall like that, especially since I played through the game three times to verify I was really stuck; twice on the same emulator, and a third time with another emulator that also softlocked. Even though I was getting tired of repeating the early parts of the story, I caved and bought the game. I had to, I was hooked. I had played the equivalent of a demo and was now convinced to buy it.

The Development Structure

We cannot talk about Metal Gear without talking about Hideo Kojima at some point. The dude is synonymous with those games because he’s the main creator of the first game, he’s the most important voice in their development, but he’s far from the only one. Case in point, the director of Metal Gear: Ghost Babel is Shinta Nojiri. Hideo Kojima was only a supervisor. Shinta Nojiri in a bathtub for some reason.

Shinta Nojiri in a bathtub for some reason.

Shinta Nojiri was fairly new within Konami, having only worked on the PlayStation port of Policenauts. After that game, there’s a very conspicuous gap in his resume before he worked on Metal Gear: Ghost Babel. I think he might have worked uncredited on Metal Gear Solid as a sort of fixer. Someone who comes in to help complete a project, usually accompanied with ungodly amounts of crunch. It’s conjecture on my part, but it would help explain why this very young inexperienced developer was then chosen to direct Ghost Babel.

Shinta did not make the game alone. The game was developed with the help of TOSE. Just to jog your memory, they are a shadowy Japanese company that works as a secret contractor, often even as a subcontractor. They’re a large company, responsible for the development of many games and neither the company nor their employees receive credit for their work. The stories we hear about their development structure is that you send them as much design elements as possible and they finish the game on time and on budget, without an iota of effort above that. They are not a studio that goes beyond what is requested.

With the development of Metal Gear: Ghost Babel, a different approach was taken. Shinta Nojiri actually moved from Tokyo to Kyoto and was physically embedded within the offices of TOSE. It’s the first time I hear of a developer physically moving to work with TOSE. It obviously helped to bring the game to fruition, but Nojiri was the only Konami developer working directly with TOSE. I think the game’s flaws exist because he was the only person from Konami supervising the work. There was only so much he could do to bring the tender love and care a game of this scope needs. Case in point, the level design.

Level Design Makes or Breaks a Classic

I used to hold Metal Gear: Ghost Babel in very high regard. I had played it young, and loved it immensely, as my first stealth action experience. Replaying it for this article, I have to tamper my reverence due to its level design, which left me cold upon this replay. The level design in MG:GB is messy.

It starts with the big picture. The game is divided in chapters. You cannot go back to previous sections of Fortress Galuade unless that’s what happens in the chapter. A game divided that way is not a design problem, but the game only saves at a couple of discrete points within each chapter. Usually, that’s after a story event. So if you save in the second-to-last room before a boss and reload the game later, you’ll be put back at the last story point instead. That might be halfway through the level, forcing you to replay a large section of the game. I wouldn’t even consider this a problem on PlayStation, but on a portable system it’s not fun to lose a ton of progress whenever you save and quit. I presume that game is divided that way to simplify the development structure, with the problem of lost progress due to a limited save system seen as a necessary compromise.

Now we can go into the design of each level itself. Every room, taken in isolation, is okay. Some rooms only exist to enhance gameplay, but I can forgive those rooms. It’s how each and every room connects with one another that makes no sense. If you enter a building and explore different floors of that structure, the size is different from floor to floor. Elevators are placed where it makes gameplay sense, not architectural sense. Security rooms, full of traps and hazards, are placed between two corridors, protecting the entrance of nothing of value. You might think this has no impact on gameplay, but with a game focused on exploring bases to stealthily accomplish nebulous objectives, it’s important to understand the layout of your environment. It’s the game’s greatest flaw, and I think the level design problems are due to TOSE staff designing the levels themselves. It looks like something that was made quickly with the tiles they had, without a lot of attention paid to the players’ sense of space. Here’s a great example: the power plant mission.

You have to find four structural pillars inside a power plant, and put C4 on them. You do that because you intend to collapse the whole building to cut the power to Metal Gear. It’s an inventive objective, made frustrating by the nonsensical floor plan of the power plant. The layout does not make sense, so finding the pillars turns into exploring every room from corner to corner to make sure you haven’t missed one. You cannot simply go to the four corners of the map to logically find the pillars. The dreaded box factory is another potent example. It could be made more fun if the relationships between the conveyor belt exits and the lower floors made more sense. Instead, you’re dealing with a building without logic. That makes the game’s worst level even more frustrating.

The whole game is strewn with those little paper cuts. You’ll often find dead ends with no usage whatsoever in a level. That’s commendable since it could add realism (dead ends without a clear purpose exist in real life after all) but in this case it doesn’t work. Some of the connections between areas are visually confusing. In the second level, you have to find a side outcropping of a building to reach a back entrance. It does not look like there’s an access hatch there. The outcropping in question. You need to walk down to enter that building!

The outcropping in question. You need to walk down to enter that building!

I think there are issues with readability because of the colour limits of the Game Boy Color. They can’t always use a different shade to indicate a different element. When you get in the sewer, there are puddles of water on the ground. So far so good. Some puddles look awesome. Sue me, I love little details like that. Other puddles are far more difficult to visually understand. This puddle looks like a hole in the ground you should fall through.

This puddle looks like a hole in the ground you should fall through.

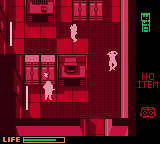

Often, you can’t make sense of the areas you’re looking at. I think they knew about the problem, since they always introduce a new area without enemies or challenge so you can figure out your environment without stress. On the other hand, the game features thermal goggles that work during the whole game. For a 3D game with an engine that allows post-processing, it’s trivial to implement. But we’re talking about sprites and tiles here. This meant that every single tile in the game had to be drawn twice, just so you can use the goggles anywhere you want. It’s incredible attention to detail that I’m surprised to find in this game. Most of the game can be played this way.

Most of the game can be played this way.

Damn Boxes

I could not talk about this game without talking about one despicable level: the box factory. Just like in The Simpsons, the box factory is boring as shit.

Just like in The Simpsons, the box factory is boring as shit.

In the middle of the game, you’re sent to this building with conveyor belts that move boxes according to their colour. You have to hide inside Solid Snake’s famous box disguise and slowly wait on the conveyor belts to fetch other coloured boxes. Those boxes then allow you to go through different directions in the conveyor belts to find more boxes and ultimately the exit. Keep in mind that you can change your boxes’ colour when on the conveyor belt, meaning you have to discover paths by constantly switching between three coloured boxes.

When I say it like that, it doesn’t sound too bad. The problem is the execution. The colour sorting machines are too far apart, meaning you often have to go through two screens before you come to another colour change. The conveyor belt layout is confusing, centred around a circle around the start without a visible destination. There is no logical connection between the conveyor belts and the segments on foot. You exit the belts in places that make no sense at all compared to your belt position. And finally, it’s slow. You move slowly, with a repetitive music to boot, so everything in that damn factory takes forever. It takes so long, and makes so little sense, you get bored and just want it over. I presume many players abandon the game at this point. I very nearly did myself. If not for the fact that I played this game in the 2000s, when I had little income and needed to justify the money I spent, I would have stopped this game right there.

So look up the solution online. Do not hesitate. The box factory does not deserve your attention. Look up a walkthrough and just get it over with. It’s a black mark on an otherwise very fun game. If you want to find beautiful level design that showcases the capabilities of the game, you have to play the VR Training.

VR

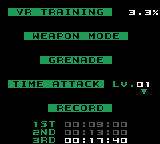

The VR challenges redeem the level design for me. Yeah, the story levels aren’t as good as they should, but those VR missions are so much fun. The portable nature of Game Boy even allows you to knock out a couple of them anytime you want, without having to suffer the slow loading speed of a PlayStation’s CD drive. Truly a great part of the game that I wished was even longer.

The VR challenges made me appreciate stealth gameplay, and I ended up wanting more. This ultimately led me to Thief II: The Metal Age on PC, the most accomplished game I ever played in my life. But you’re not here to talk about the VR challenges or Thief II, you’re playing Metal Gear for the story, right?

The Goddamn Story

By the end of Metal Gear Solid, Solid Snake has rescued the girl (or the boy?), killed his clone brother, resolved his painful relationship with the robot ninja, and solved the mystery of people mysteriously dying around him during his mission. I guess he also saved the world. It’s a convoluted ending, but it fits together nicely. Then the second game on PlayStation 2 happens, and I feel like the whole story fell off the tracks. There’s supposedly an AI colonel, incest, I think actually two cases of incest, ten Metal Gear vehicles who look like noodles, there’s a vampire in there somewhere, another AI who runs the world, and the main villain of our story is the arm of Liquid Snake attached to Revolver Ocelot thus controlling him. Oh and you don’t play as Solid Snake, you play as a new character that’s really hard to love. It’s the worst of Japanese excess. Metal Gear Solid 2 goes up its own butt, comes out of the mouth, and goes back up its own butt a second time for good measure.

I’m happy to report that the story of Metal Gear: Ghost Babel is very simple, like the early MSX 2 titles. It’s got a proper, if barebones, Metal Gear story. There’s the same difficult relationship with war and conflict, the same questions raised at our sheltered way of life. It’s just on Game Boy, so it’s very limited in scope. Their efforts are commendable, but sometimes you can’t help but laugh. After every boss battle, you’re treated to the exact same thing. The defeated boss lies on the ground explaining their whole terrible life to Solid Snake. Think about how ridiculous that is for a second. On top of that, they all have horrible circumstances imposed on them, making them into perfect victims not deserving of death. The same thing happened in Metal Gear Solid with the same lesson: in war, everyone is a victim. It’s commendable but by the fourth time it happens you start to giggle at the pattern repetition. It feels like someone writing a copy of Metal Gear Solid, and I mean that in the best possible sense. Hideo Kojima would make his games ever more convoluted, and I think their story lost the simple charm of the first three Metal Gear games he made. Metal Gear: Ghost Babel, because it was developed before the release of Metal Gear Solid 2 can only ape those three simpler titles, and the game is better for it.

I guess I have to talk about the canon status of the game. There are discussions that the game is the final VR training of Raiden or that the game isn’t canon. It leaves an aura of uselessness around the game, putting the game in a state of limbo, telling prospective players that it does not matter. That’s a thing I do not like. Too often these days, canon status equates to existence. If a piece of art isn’t canon, it no longer exists. Regarding these matters, I instead take an author-centric approach. The game was made with limited input from Hideo Kojima, the main driving force behind the story of the franchise. Kojima never revisited its events, so that’s where it stands. No need to attach a strict label when the game’s production history easily describes its position. Is it canon? It doesn’t really matter.

If we need to talk about one label, it’s that it was designed from the get-go as a gaiden title. Japanese gaidens (literally side story) are stories that stand to the side of the main narrative thrust. They tend to focus less on respecting the exact details of a timeline, and to instead provide further stories surrounding the characters. Those stories are not meant to propel the narrative forward, but to be a way to spend more time with the characters of an already existing narrative. In our specific case, Metal Gear: Ghost Babel seems to disregard the events of Metal Gear 2, and seems to happen instead of Metal Gear Solid. Maybe I don’t pay enough attention to tiny details, but to me this makes no sense. Ghost Babel could totally happen between the second MSX game and Metal Gear Solid.

A Working AI

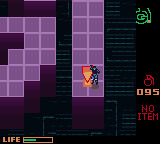

I’ve talked time and time again that the Game Boy can’t do convincing artificial intelligence with enemy characters. Its processor is simply not fast enough to reserve large chunks of computing time to calculate complex decision trees with enemy states. Instead, enemies resort to simple clauses. If the player character is close to you, run towards him. That sort of thing. Then how can the Game Boy Color manage to have stealth gameplay with somewhat realistic enemy soldiers?

The old Metal Gear titles ran on the same family of processor as the Game Boy Color but at half the speed, and they managed to have somewhat convincing soldiers with only half the processing power. They managed it by designing around the problem. A clever example is the simple enemy detection phases. When playing the game, you are either undetected in the green phase, actively hunted while under a red alarm, or restoring from an alarm in the yellow caution phase.

With those three states, you simplify a vital element of stealth gameplay: who knows where you are? All the soldiers all know the same thing at the same time. Punching enemies in the back or killing them with your silenced pistol changes nothing. Soldiers have no sense of the absence of other soldiers. They are bothered by Snake standing in front of them or making noise close to them. That’s it. There’s an exception for soldiers silently dying in front of them, but that’s it.

These simple states also include all the other enemy types. Cameras? Soldiers on rails. Dogs? Melee range supercharged soldiers. No enemy in the game deviates from the core principles. Even bosses either act like soldiers or like normal video game enemies that always know where you are. There’s nothing complicated about their AI.

If we compare to something like Thief II: The Metal Age, which features no centralized alarm system, guards become personally aware of your presence and make noise to warn other guards within earshot. It’s incredibly complicated to implement with each soldier having independent awareness of the player. Let’s look at how the simple system of Metal Gear: Ghost Babel is implemented.

Green

Each state allows soldiers to act differently. When you are undetected in the green infiltration phase, soldiers have a predefined path that they follow. Maybe there’s a chance they fall asleep, maybe they randomly turn around but they’re on a predetermined set of simple coded clauses. In other words, that’s the phase where the developers have hard-coded all the interesting events. This is also a phase where making noise can attract the enemy soldiers. You can run in water or specific flooring to make noise that attracts nearby soldiers. Knocking on walls also attracts enemies to the spot where you made the noise. They don’t see you, so they don’t trigger an alert but noise will pop a question mark above their head and send soldiers towards the noise. It’s different from visual detection, but it’s not more complicated to code. It’s just a different event.

Red

You become visually detected by standing in front of soldiers. They have somewhat of a vision cone on Game Boy, but it’s pretty much a straight line up to a certain distance. When that happens, you move to the alert phase. Here, soldiers are relentless, but their coded actions are fairly minimal. Enemies remember the last position where you were spotted and head there. Enemies have no knowledge of where Snake is during an alarm, only the last position where he was spotted. Of course, if there are enemies constantly looking at you then they always know your position since you’re always under a vision cone. If they get close enough to you when they spot you, they shoot you or hit you. Killing enemies during this phase immediately respawns another enemy that enters the screen from one of its doors. That’s how you can discover that the game can only manage three soldiers per room. Kill as many as you want, you will only ever see three enemies at the same time. Under this phase your job is to make sure none of the three enemies see you until the timer drops to zero. You then move on to evasion.

Yellow

Under the yellow phase, enemies no longer roam around your last known position. They randomly search in the screen you’re in. Noises attract them with a question mark once again, and once the timer for this phase hits zero, you’re back in the green infiltration phase. Enemies quickly go back to the screen’s border to disappear, or return to their designated route once you finish the phase.

What AI Means

After all that detailed analysis of enemy patterns, if you have one thing to remember is that those early Metal Gear games aren’t much more complex than Pac-Man. There are more things that can change the state of the game, but nothing exceeds the complexity of a game of Pac-Man, down to the limited enemies on the screen at the same time. Reading about how the four ghosts act in Pac-Man, it’s shocking how similar it is to Metal Gear. Of course Pac-Man is much simpler, but the underlying logic is in the same realm of complexity, just expanded and used to achieve more complicated gameplay. Which explains why you can have complex enemy interactions on Game Boy: it’s not as complicated as you think, it’s the way everything is arranged in phases that makes it appear complicated.

When you take a step back and look at the whole game, they also break up the game into smaller events to vary the gameplay, so you never get bored. There is water in the sewers, sections filled with security cameras, rooms of invisible lasers, two nonsensical door puzzles, darkness that requires thermal goggles, poisonous gas, and very dangerous dogs. Since they break up the gameplay so often, you don’t really have time to stop and consider the shallowness of the AI. It’s a well-made game in terms of pacing, except for the boxes level.

Music

Metal Gear: Ghost Babel has music by Norihiko Hibino and Kazuki Muraoka. A lot of the music compositions in the game, and sound effects for that matter, are adapted from previous MSX 2 titles and brought to Game Boy Color. So you get Game Boy versions of classic songs from the old games. Since those tunes were originally composed for the MSX 2, it works perfectly fine here. From chiptune on MSX 2 to chiptune on GBC, there are no issues here. It’s incredibly good music. I feel like they tried to bring the vibes of the Metal Gear Solid soundtrack when adapting those songs, since the music has a lot more echo than on MSX, and a much harsher sound. It’s Game Boy, so they couldn’t use more bass but they tried to imply a sound with more bass. They walked on the edge of the sword to great success here: You have the classic melodies from the older games with the muted ambiance of the PlayStation game. On PlayStation the music, while still featuring complex melodies, is more focused on ambiance than composition.

Conclusion

Once I was done with Metal Gear:Ghost Babel back in the early 2000s, I did the only sensible thing a kid without a PlayStation could do: I bought the PC version of Metal Gear Solid. This version of the game is still playable today, courtesy of GOG.com. It’s a solid port. I don’t remember having any issues with the game back then. They’ve adapted the Psycho Mantis fight, and you lose some graphical effects, but the game runs better and at a much, much higher resolution. Also, it doesn’t have the jiggling textures typical of 3D PlayStation games.

I liked it a lot back then. I afterwards tried to play Metal Gear Solid 3 twice. Once on PS2 and a second time on 3DS of all places. I could not care enough to play it. I recently gave a shot to Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain, and while I was utterly impressed by the depth of its gameplay systems, the game felt too repetitive for me. I also felt that the secret twist of the game was ruined by refusing to have David Hayther voice the original Big Boss. I guess Metal Gear never really impressed me outside of the revival on PlayStation and the Game Boy Color experiment. I’ve greatly appreciated the replay I did for this article, and recommend it, even though it’s far from perfect. It’s wonderful that it exists, and it’s the sort of game no one expected to see on Game Boy Color.

This article was first published on the .

This article was last modified on the .