Game & Watch Gallery

- Japanese release in February 1997

- North American release in May 1997

- European release in August 1997

- Australian release in 1997

- Japanese release in March 2000

- Developed by Nintendo

Re-Revisited

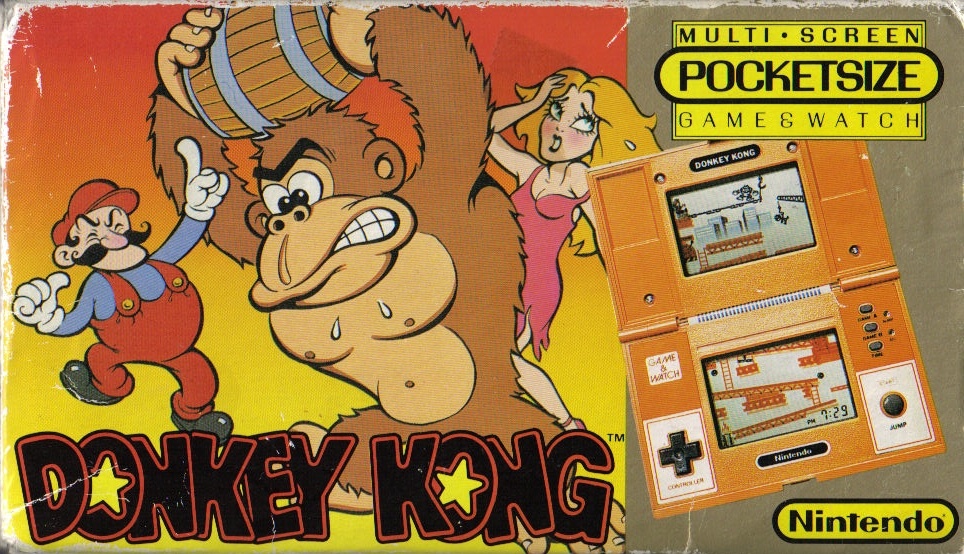

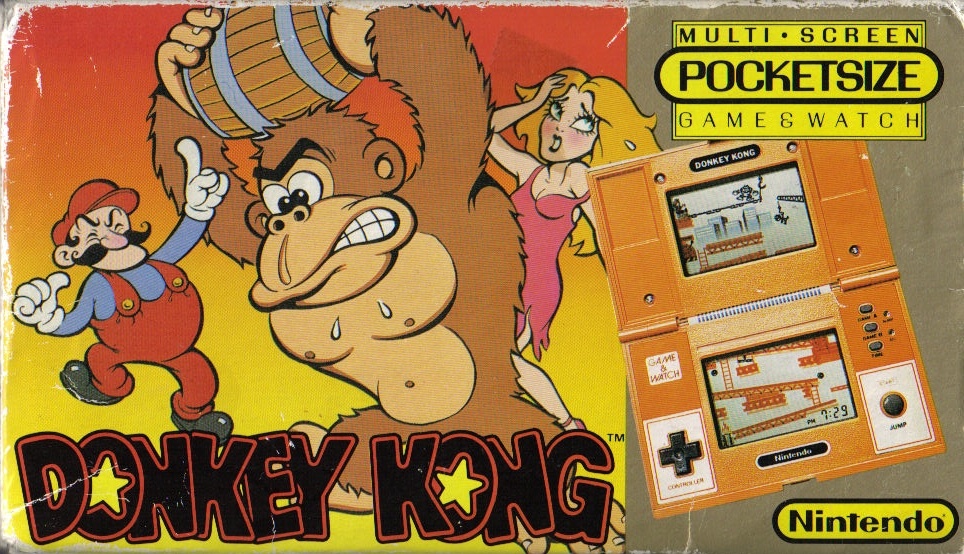

For years, my local game store had, behind its glass case, a Donkey Kong Game & Watch unit for sale for around forty-five dollars. Compared to prices you find online, this felt reasonable. I would look at it every time from behind the glass case, just admiring it. One day, I got bold and asked the employee if I could hold it. That was a mistake; once I had held the Game & Watch in my hands, I was hooked. Even though it had no batteries so I could not play it, just holding it in my hands really shook me; this was not what I was envisioning. I expected a device completely divorced from other Nintendo portables. Quite the contrary. It felt like I was holding a smaller, flimsier DS Lite. Peering over it, I saw defects that explained its low price. The metal top had lots of scratch marks and was starting to peel off. When open, it was missing both its decorated bottom panels. One of the metal inserts for the hinge was missing. The plastic clip to keep it closed was broken. All of those problems were minor. The store employee promised me it worked, and they’ve always been trustworthy.

I discovered many surprising things while holding it. The console is very small but sturdy. It does not feel cheap in your hands. Like I said, it even has a metal sheet on the top cover with the logos. The Game Boy never used metal for the exterior casing! It does not feel cheap, but instead feels made using economical engineering. The best example is the hinge of the device. You have the bottom and top kept together by a round metal piece inside two simple plastic hinges. But that simple hinge does not allow an electric connection between the top and bottom parts, which is needed for the second display on the top. So how did they get the signal through? They simply passed the display’s flex cable through thin slits, exposing it to the elements. The cable is somewhat protected between the two bulkier hinges, and unless you jab at the flex cable you’re not going to break it. This is incredible due to its simplicity. Another cost-saving measure is the battery housing. It’s very simple, with no spring to hold the batteries in place, or a screw to keep it closed. If you slide the plastic cover, the batteries come flying out, and you lose your set alarm and top score. Nintendo included small stickers in the boxes to put on the cover and prevent a curious kid from opening it. It’s not strong childproofing, but it has the benefit of being cheaper than a screw.

I could not put the little machine back in the display case after holding it; the Game & Watch had seduced me. I happily paid for it and put it where it felt the most appropriate; in my coat’s breast pocket. I then stopped at a big chain store to buy its frankly esoteric button cells (two LR44 batteries, if you must know) and went home. My Donkey Kong Game & Watch.

My Donkey Kong Game & Watch.

I put the tiniest tie wrap I could find to hold the two pieces of the plastic hinge. The front panels, which looked like they were initially glued on the front plastic, don’t affect the experience. I know what they looked like, and the unit is fully functional without them.

I have to say, I initially thought the electronics were broken. The batteries were so foreign to me that I put them in backwards. By the way, those small watch batteries can kill you if you swallow them. They leak their acid in your stomach and intestine. Keep them out of reach of children! I finally figured out the batteries, and the system came to life.

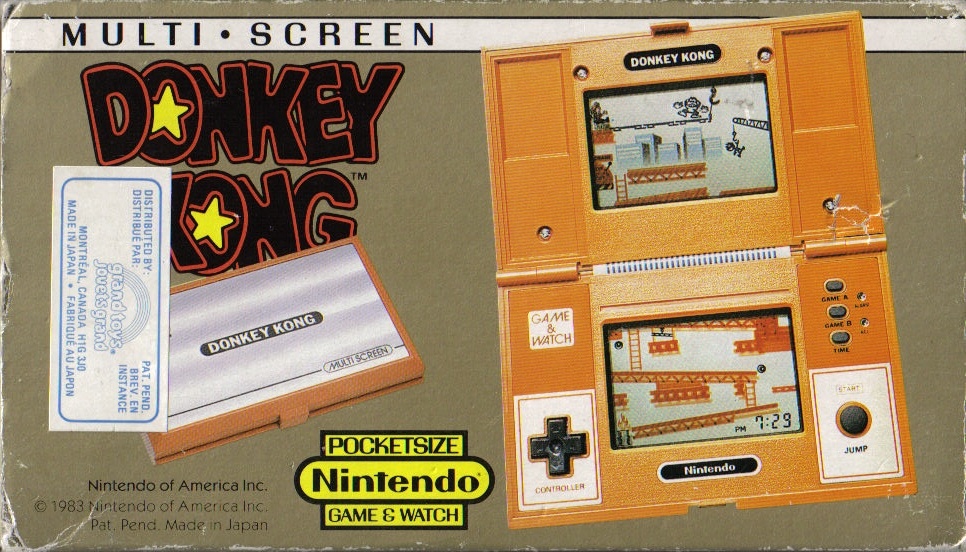

The initial box for the American release.

The initial box for the American release. The back of the box, with the label of a Montréal toy store!

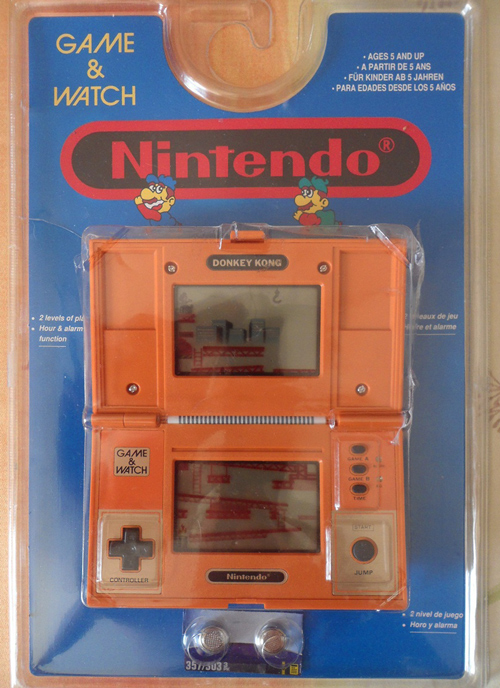

The back of the box, with the label of a Montréal toy store! Nintendo later sold Game & Watch devices through third parties. Nintendo would never design such a terrible blister pack.

Nintendo later sold Game & Watch devices through third parties. Nintendo would never design such a terrible blister pack. Or that one.

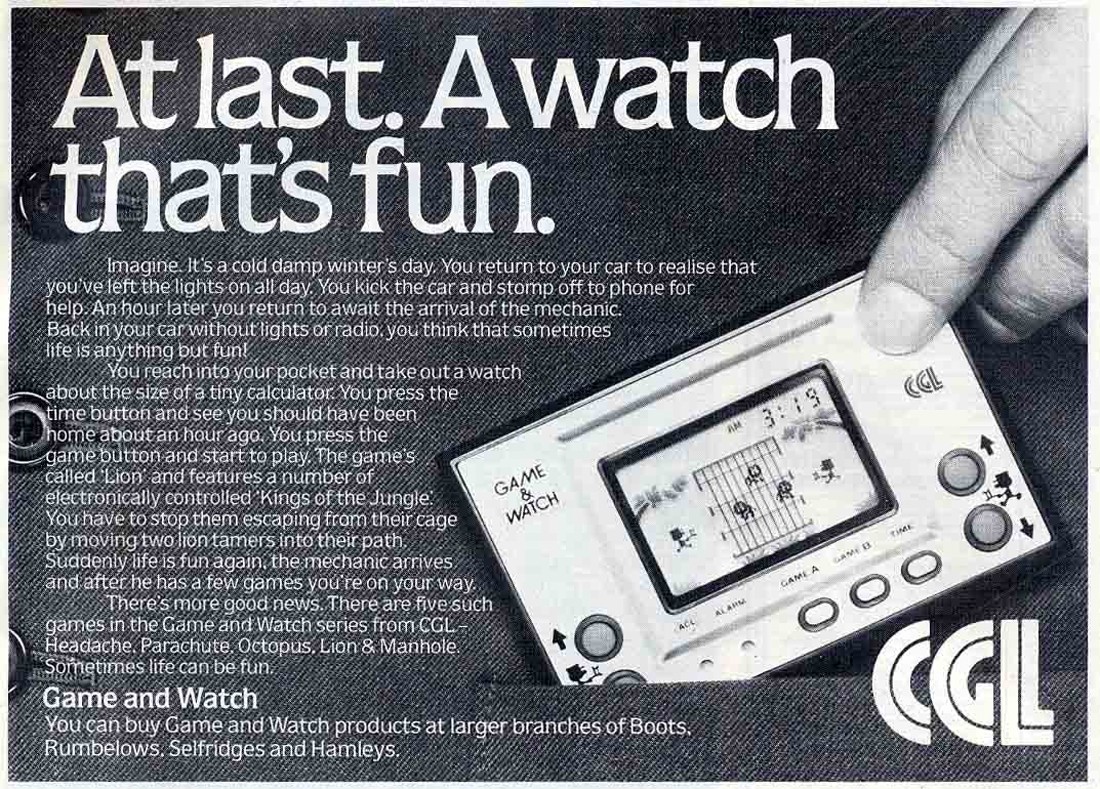

Or that one. In the UK, Nintendo even sold their Game & Watch games through CGL, which rebadged LCD games from multiple companies.

In the UK, Nintendo even sold their Game & Watch games through CGL, which rebadged LCD games from multiple companies.To get some context, start by watching the Japanese TV ad for Oil Panic and Donkey Kong. It’s interesting to see how they were marketed, and that they each cost the equivalent of 25 US dollars in 1982, around 50 USD today. The first thing that captures my attention is Nintendo’s steadfast commitment to making all Game & Watch systems a functioning clock. Turning it on for the first time presents you with a blinking 12:00, imploring you to set its time. It is literally in the name (Game & Watch), and I guess you can use the system as an alarm clock on your bedside, but it is somewhat surprising. Equally surprising is the lack of any volume control. No mute, no nothing. Considering this device was meant to be played during a busy commute, I’m puzzled as to the absence of those controls. I’m sure many Game & Watch devices had their speaker wires cut by savvy parents wanting a moment of silence.

The gameplay is sublime because it’s designed in lockstep with the limited display. That is the strongest point of praise you can give a Game & Watch. I have talked at length in previous articles about the limited nature of the Game Boy’s screen. The Game & Watch’s liquid crystal display is even more primitive. It is the same limited technology that you will find in a pocket calculator.

Since a calculator display has no discrete pixels, only segmented elements to turn on or off, you need to design your game around the constraint that no two elements can ever overlap. Imagine it in the context of the Game & Watch I own, Donkey Kong. In the arcade, Donkey Kong throws barrels that roll down the girders; the very same girders that Mario walks on. When you get hit by a barrel, it’s because Mario physically touched a barrel. No such thing can happen on the Game & Watch version. Your character stands on the girders in fifteen discrete positions, but you can’t have the barrels intersect your character. The decision made here was to put them very close to the side of the player character. And here comes the Nintendo R&D1 touch: there is a delay between the barrel appearing right next to your character and the barrel hitting you in that position. They implemented a slight delay before you get hit to account for the barrel’s rolling! They are working with your imagination of the barrel’s movement, which gives you the ability to jump above the barrel just like the arcade game.

On the bottom screen, you are dealing with barrels, but since the technology cannot properly render the frenetic barrel action of the arcade Donkey Kong, the developers added one more challenge than just the barrels. You also have girders on cranes above your head that can kill you if you jump. Once you clear those challenges, you have a ladder to ascend to reach the top screen. Girders can hit you on the way up, and barrels can hit you at the top of the ladder. Once you reach the very top, you are right underneath Donkey Kong, who has been throwing all the barrels you have been encountering. He moves from left to right, and throws barrels straight down. His arms are different segments from the rest of his body so he moves, picks up a barrel, and then throws it, and all those actions are separate and clearly telegraphed. On the top screen, you have to push a switch, and then jump right to reach a crane, while dodging Donkey’s barrels. You have to jump to hit the crane, which swings left and right. This means you can miss it and lose a life. Each time you reach the crane, you get to remove a bolt from Donkey’s platform. Remove all four bolts and Donkey falls headfirst on the ground. You then repeat from the start.

The controls to achieve all these actions are wonderful. Other dedicated consoles of the time were not known for their great controls, but Nintendo always stood above the rest. There are some issues; the Jump button is made of soft rubber instead of the expected plastic, and the reset buttons are very small and recessed inside the case. They’re meant more for your nail than your finger. However, the star of the show is the directional controller, the Plus Button.

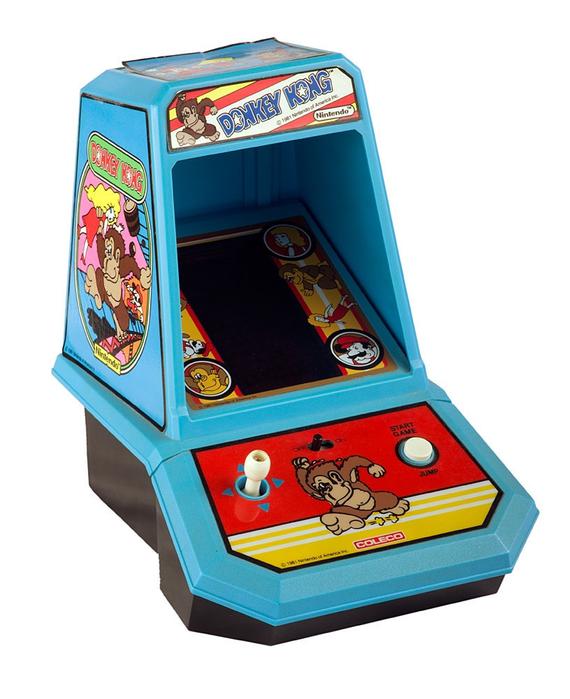

Now known as the D-Pad, the Donkey Kong Game & Watch is literally what it was invented for. The people at R&D1 needed a way to bring the joystick of the arcade to a portable machine; their solution was so natural we could not imagine video games without it anymore. All previous Game & Watch games required at most four buttons to play, which back then they simply made into separate buttons on both sides of the display. You then covered all the buttons with your thumbs and pressed with your fingertip for the top button and your joint for the bottom one. But to adequately convey the action of the arcade Donkey Kong, you need the four cardinal directions and jump. Since no one has three thumbs, they needed a new control system for the game. Could they have simply put a small arcade stick on the system? That’s what Coleco did. A Coleco tabletop game.

A Coleco tabletop game.

But Coleco’s licensed game was a tabletop; you did not fold it nor hold it while playing, you merely set it down on a table. This meant it was possible to grasp the stick with the two required fingers with the system safely stable on a table. Nintendo could not do the same as Coleco. It was not reasonable to have you hold a Game & Watch while you manipulate a mini arcade stick. It’s far from ideal. So only something flat for your thumb would do, since the rest of your palm is used to hold the Game & Watch. Their solution was to flatten the arcade stick. They put a plus sign on a small ball above the four buttons. Press on the pad in one direction, and the D-Pad will push the button you want with the contact pad underneath the button creating the contact. What this means in practice is that your thumb is not managing four separate buttons but just one. Your thumb rests in the middle of the pad and moves in the direction you want to press. The Plus button is, to put it simply, genius. Nintendo patented the shit out of it, which meant everybody had to invent an inferior method to implement their own D-Pads.

I do ultimately feel a bit stupid explaining a D-Pad, since it’s so ubiquitous but sometimes we need to explain easy stuff because we take it for granted. I ultimately feel privileged to own a Donkey Kong Game & Watch, since I own the first D-Pad ever made. It’s smaller than an NES D-Pad, but unless you know it’s the first one ever made, you would never suspect it. The wizards at R&D1 got it right the first time. Strangely, they would not use a D-Pad for every future Game & Watch units. Only lids that closed and could protect it got one. This later Super Mario Bros. game got a terrible controller that looks like a Switch’s dreaded D-Pad.

Strangely, they would not use a D-Pad for every future Game & Watch units. Only lids that closed and could protect it got one. This later Super Mario Bros. game got a terrible controller that looks like a Switch’s dreaded D-Pad.

A Slow Start

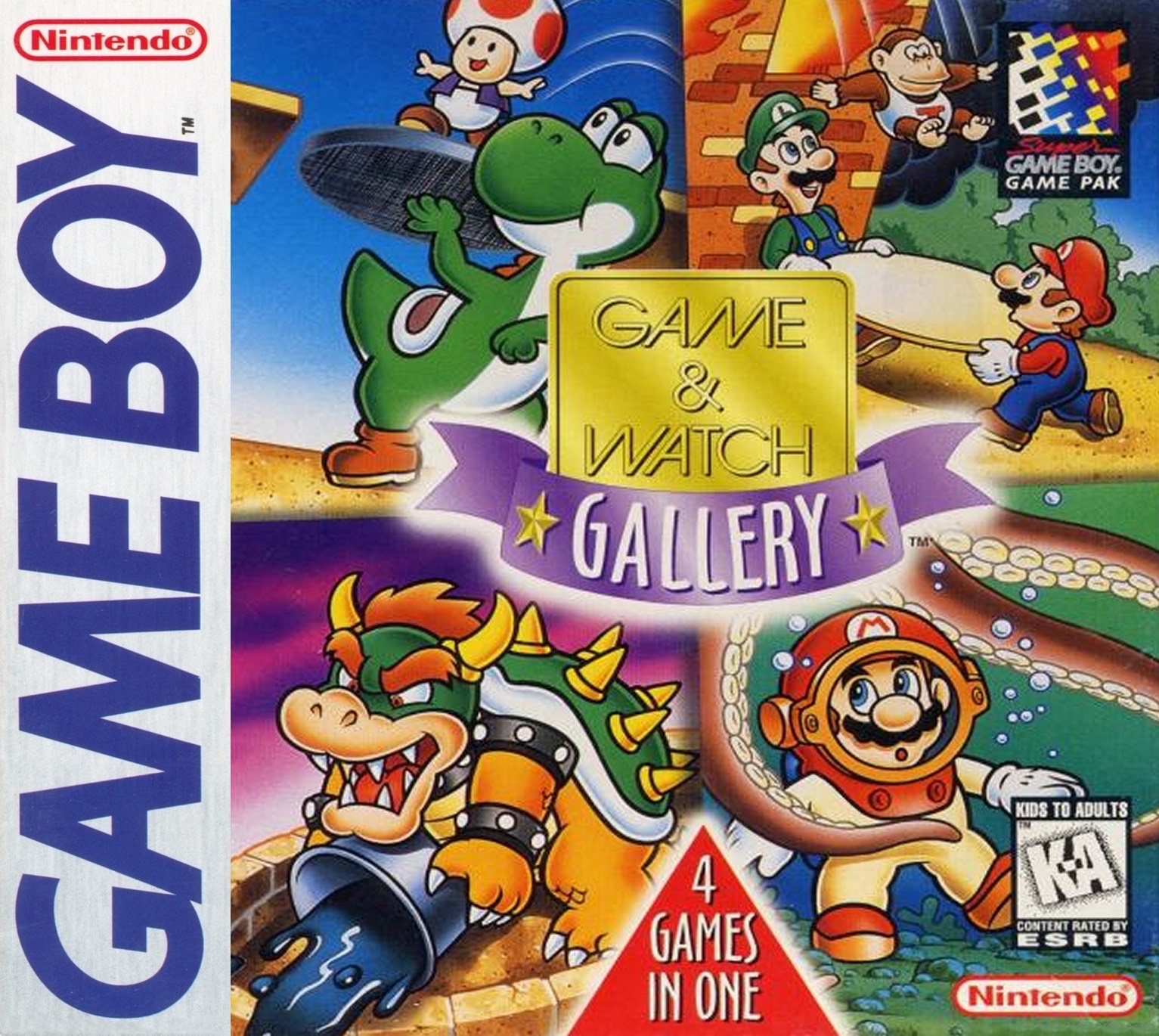

Moving on to recreations of Game & Watch portables, right when you first start Game & Watch Gallery, you can feel the energy that went into making this game. A big Mario sprite comes in to chill out on the front screen. An animated sprite this big means real efforts were spent on this game. They broke from the staid look of Game Boy Gallery. When Nintendo puts Mario in a game, it’s meant as a mark of quality.

And some of Nintendo’s best talent were working on this game. Two managers at Nintendo, Yamagami Hitoshi and Izushi Takehiro worked as director and producer respectively. You even have Tezuka Takashi, the genius designer behind Shigeru Miyamoto’s greatest games, helping out as an advisor. It seems most of the lower level staff were TOSE employees. Direct oversight of those contractors by three Nintendo employees meant that their collective efforts would be spent making the game good; they succeeded at making the general concept of the game much better than Nintendo’s last Game & Watch collection, Game Boy Gallery.

Classic and Modern

The secret to Nintendo’s improvement: the Modern and Classic dichotomy. Game Boy Gallery offered new graphics but the same gameplay as the original game. Here, we instead have two distinct modes. First, a faithful recreation of the original game called the Classic Mode. Second, a reinvention of the game with new sound, gameplay, and graphics using characters related to the Mario franchise called the Modern Mode.

Classic Manhole

Classic Manhole Modern Manhole

Modern Manhole Classic Fire

Classic Fire Modern Fire

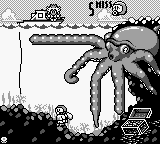

Modern Fire Classic Octopus

Classic Octopus Modern Octopus

Modern Octopus Classic Oil Panic

Classic Oil Panic Modern Oil Panic

Modern Oil PanicThe modern versions all have new bells and whistles. For example, the modern version of Octopus slows downs Mario if he has collected more treasure. This introduces an element of gambling; should I keep plundering, knowing that I will be slowed down significantly when going back to the surface? This variable walking speed is possible because Mario visibly walks between the discrete points of the ocean floor. He simply walks slower between them when carrying a heavier load. This detailed mechanic was impossible with the LCD screen of a Game & Watch.

Stars and Unlocking

Another improvement that the game has over Game Boy Gallery are unlockable rewards. You receive a star every 200 points you accumulate in all the game modes, for a maximum of five stars per mode. With each game having four modes (Classic A and B, Modern Easy and Hard), you have a ton of star gathering to get through.

As a reward for accruing stars, you can unlock viewable versions of Game & Watch games with a short paragraph about the game. Emphasis on viewable. The games are not playable, contrary to what you will read online. This confusion is widespread, and baffling.

How You’ll Play

The game flow for me is somewhat frustrating. Since you want to get stars, you need to play all the easy modes, but they are so easy they’re boring. I end up not paying enough attention because I’m bored, and I start making mistakes. Since the games reset their speed when you lose one of your three lives, I get even more bored after a mistake because it becomes even easier. The harder modes are a bit better but they’re still repetitive games. You still risk losing your focus and making mistakes. To alleviate that, I tend to play in shorter sessions. It’s what I recommend; Game & Watch Gallery is better played in fifteen to twenty-minute increments.

Interrupt Save

You’ll want to play in such short bursts, and the developers have thought about it too. They designed a wonderful feature to save your progress; the game offers what it calls interrupt saves. If you pause a game, turn off your Game Boy, and turn it back on again, the game will allow you to continue where you left off. It achieves this magic trick by saving your game every time you press Start. To the modern player, this might feel like save states. However these cannot be used for save scumming since the save disappears the moment you resume your game. You have no ability to preserve a previous save. I had no idea that this functionality existed when I was a kid, since I could not read the English explanation. It took me a long time to figure out how sometimes when I turned on the console it allowed me to start a game in progress.

Had I been able to read English, I would have gotten an explanation through the game’s hint system. Periodically, the game will give you hints about different aspects of the game.

Quality

I have to admit, as I wrap up, that I am a bit underwhelmed by the games on display here. I have played Game & Watch Gallery 2 a lot when I was a kid, and my experience of this first title is inevitably tainted by the sequel. The four games on offer here are fine, but their modern versions are all too close to the classic versions. They are all additive versions and not reinventions. Game & Watch Gallery 2 offers a more eclectic selection. Games like Vermin will change the perspective and the fail state of the classic version; only the player action will remain the same. This variety will make the sequel a much better game.

Conclusion

Playing a Game & Watch explains so clearly how Nintendo approached the Game Boy. Their main competitor, Sega, produced a portable version of their somewhat successful 8-bit Master System console. NEC did the same thing by making a portable PC Engine. R.J. Mical and Dave Needle designed what would become the Atari Lynx based on their experience designing the powerful Amiga computers. All those portable consoles featured colour screens, large plastic housings, high prices and abysmal battery life. Nintendo, ever the outlier, instead looked to expand from its diminutive Game & Watch line. It chose to use a shockingly limited screen, coupled with a CPU architecture known for its low-power qualities, to achieve an impressive fifteen to twenty hours of battery life with a competitive price. Where the competition tried to cram TV experiences into your palm with battery-guzzling failures, Nintendo R&D1 simply evolved their best-in-class Game & Watch experiences for battery-sipping success.

No wonder they were so reverential to their Game & Watch games, trying twice to update them for the Game Boy. Those games were the true ancestors of Nintendo’s Game Boy. Their second attempt at redefining those games was clearly a success and with their next collection they would reach surprising heights. The Australian cover. If you remember my article about Game Boy Gallery, you’ll remember why this game is a sequel in Australia.

The Australian cover. If you remember my article about Game Boy Gallery, you’ll remember why this game is a sequel in Australia.

This article was first published on the .

This article was last modified on the .