The Final Fantasy Legend

- Japanese release in December 1989

- North American release in September 1990

- North American release in 1998

- Reprint

- Never released in Europe

- Developed by SquareSoft

A Tale of Two Printings

The Final Fantasy Legend came out so early in the Game Boy’s life as to be unbelievable. It is surprising that Akitoshi Kawazu managed to produce a game that understood so well what the Game Boy was capable of not as just a piece of silicon but as a physical object, a portable console used by people every day. The other games that came out in 1989 in Japan from third-party developers look woefully maladjusted in comparison. But I didn’t play The Final Fantasy Legend as a 4 year-old kid in 1990 when it came out in North America. I played it in 1998, as an 8 year-old when it was reprinted by SunSoft following the Final Fantasy VII craze that swept the world.

I’ve got to say that I’ve already told the tale of my first encounter with the Final Fantasy reprints in my Final Fantasy Adventure article but I have to kind of tell that tale again to get you, dear reader, to understand my outlook on The Final Fantasy Legend.

Story retold

In early 1998, Sunsoft picked up the rights to the forgotten Final Fantasy titles that SquareSoft did in the early ’90s. Four games that featured the title of the hottest game in the world in 1998, Final Fantasy VII. There wasn’t a better time to republish those four games. That’s how I came into contact with them. I first saw them in a store and convinced my mother to buy me one of those games. I was just so excited to see Final Fantasy, which I had played on SNES and heard so much about. Now suddenly there were not just one but four Final Fantasy games on Game Boy that seemingly came out of nowhere! Being the completionist that I was, I bought the first game in the series to start from scratch. I still vividly remember the expectations that overcame me as I looked at the box, excited to play it when I got home. I had not brought my Game Boy with me to the store, so I got to reading the manual.

I read the manual cover to cover multiple times in that long car ride back home. Remember that I am not an anglophone and had very limited abilities in English at that time. I could somewhat understand what was written but I didn’t get everything. It didn’t stop me from trying though. It emboldened me! That long car ride back home reading the manual is a big reason why I cannot divorce The Final Fantasy Legend from its manual. Other Game Boy games where I pored over the manual (for example, Dragon Warrior III or Pokémon) have not left me with such a deep impression. The manuals are not bringing you a different outlook on the game and you can reasonably expect someone who never reads the manual to get the same thing out of the game. They’re not essential. The Final Fantasy Legend has a manual so divorced from the rest of the game, so Americanized with its obvious Dungeon & Dragons influences, that it portrays a completely different tableau than the chibi-inspired squat little Japanese characters that inhabit the game. The game tries to tell a simple, straightforward and passionately weird story while the manual tries to sell you on this operatic, Wagnerian opera that The Final Fantasy Legend is not. This clash awoken a feeling of despair as I finally started playing; I felt like the characters of this game were delusional about the world they were actually living in. I imagined these valorous medieval stereotypes stuck in a sanitarium.

Now is as good a time as any to mention that the game is not really a Final Fantasy title. It has been strongly influenced by the series since it was produced by Akitoshi Kawazu, who worked on Final Fantasy I and II but it’s only a Final Fantasy title outside of Japan. It used the title SaGa in Japan. Most of what I know of how Kawazu created the first game of the SaGa series comes from the Retronauts podcast. Kawazu was one of the creators of the original Final Fantasy along with Hironobu Sakaguchi and Nasir Gebelli (the Iranian-American Apple ][ star programmer!). They all made the first Final Fantasy game a success and they teamed up again on the second one, using Kawazu’s new idea for activity-based progression. What is that? Basically, you use a sword, your character gets better at using a sword. You get hit, your defence points increase. It’s straightforward but it led to overtly specialized characters who could not do more than one thing reliably in Final Fantasy II. According to Kawazu himself (who talked about this with Jeremy Parish in an interview), nobody else but him understood his progression system at SquareSoft so he was the only one championing it. He moved on to SaGa on Game Boy and brought his activity-based ideas with him while Final Fantasy went back to the first game’s level-based progression for its third game on NES. So you end up with him and Koichi Ishii, who was mostly responsible for the scenario, being the two important figures of The Final Fantasy Legend. Koichi Ishii would later be the main producer of Final Fantasy Adventure and is thus the Mana series creator.

The World of Continent

Let’s talk about the game in front of us. It was made by a very peculiar developer, but we didn’t know that back then. Back then all we had was brand recognition and the game in front of us. I don’t think this original experience I had with The Final Fantasy Legend can ever be replicated. It was 1998 and walkthroughs were not really a big thing yet. I was stuck trying to figure it out by myself, with my limited knowledge of English. I look back very fondly on this experience.

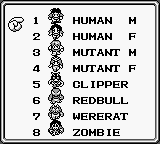

You start the game with a story scroll and move on to choosing a race. The three races of the game are its bread and butter. Let’s look at each. First you have humans, who come in male and female variety which are basically empty vessels. You pour equipment in their eight inventory slots and spend improvement items on them. Let me be extra clear: Humans do not improve unless you spend money giving them consumable items that improve their stats. You have HP, Strength, and Agility items. For humans, money is ultimately their experience points. It’s a maddening system because you have to lose a lot of time just buying and using the same items over and over again to improve your characters. Their whole progression system feels unfinished.

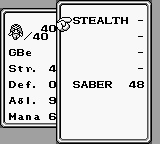

You then have mutants (Espers in the Japanese version), male and female, who work similarly to the activity & progression system from Final Fantasy II on Famicom. The more they get hit, the better their defence. The more they use spells, the better their magic stats. They’re the spell casters, so four of their eight inventory slots are reserved for spells that appear at random. So they tend to have less armour, fewer weapons, relying more on magic. The big thing with the mutants in the first Legend game is that their improvements are way too random. They do indeed improve based on what they do, but it is simply too haphazard to feel like the game is reacting to what you are doing with your characters. Character stats don’t look like they progress in a relatable fashion, but the worst offenders are the four inventory slots reserved for random spells. Spells appear or disappear after battles, seemingly at random. You seem to have an equal chance of seeing a powerful spell you like replaced by a useless spell, or even worse a spell being replaced by a weakness to a certain element. Those four slots give you the impression you have no control over mutants; that they can go from too powerful to useless in the span of one battle. Even with those problems, they end up being the most useful race. This means you need their help to win, and thus need to beg that the randomness of the game doesn’t screw you over.

Finally, you have monsters. They are exactly the same creatures as the one you fight against in battle but on your side. Often the last enemy you will defeat will leave behind their meat. Yes, I know. Anyway, you feed that meat to your monsters and they change into other monsters. They appear to change at random but there’s a method to the madness, it’s just convoluted. Can you spot the resemblance with a certain monster game here? Monsters that evolve, that you have a chance of catching yourself if you’re lucky enough at the end of the battle? It even has a staple of Pokémon: what appears to be random elements not being random at all, like the EVs and IVs of Pokémon. I’ve never seen anyone who worked on Pokémon mention The Final Fantasy Legend as an influence but I would be shocked if it did not have a certain impact.

The Adventure Begins

You start your adventure on the World of Continent, a barebones map with a bunch of castles literally called after the object you’re supposed to get from them. So you go to each castle and do what they ask you to do. Regicide, a love story between a one-eyed monster and a human king, an evil monarch, you know the drill. Actually you don’t, everything is crazy and hard to suss out.

You buy equipment and realize that the game features one of the most maddening concept ever devised: limited-use weapons. That fancy sword you bought has fifty uses and after that it simply disappears. Most of everything in the game is a consumable. You begrudgingly accept the reality of this fate, thank the stars at least armour does not have limited uses and then equip your characters. You then realize that characters don’t have specific slots for specific pieces of armour. You just equip them wherever in one of eight general slots the Humans have and four for the Mutants. This means that you have to choose if you want to have a helmet or an extra potion, especially with mutants who have limited inventory space. With these restrictions, the weird way you do certain things and the menus that cycle tiles when you invoke them you can feel the assembly code behind the game barely holding together.

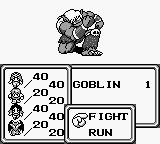

The battle system is always the most important part of an RPG. Here, what you get is a somewhat gimped version of the Dragon Quest II, III, & IV battle system. You don’t see your characters, instead you are presented with a first-person view of the enemies in front of you. Contrary to Dragon Quest, you can only physically attack one enemy of each type, having to kill the first one to get to the second. You also only see one enemy of each type on the screen. To me this always meant that enemies were all facing you in front of one another. It makes sense once you think about it. They’re conga lines of samurai and werewolves! Group attacks such as spells work the same, allowing you to hit all of the conga line in one go. You input all the commands of your characters before the turn unfolds just like Dragon Quest too. No Active-Time Battling to be found here.

Then one of your characters might die while you go through the first dungeon, a cavern with enemies that are surprisingly difficult. You head back to town to heal them at the inn. It doesn’t work. Then you go back to the manual and read about the limited lives of the characters. Each character has three hearts. When you revive them they lose one and if they use all three your characters are permanently dead, forcing you to start new characters from scratch. So if any character dies more than three times you lose all that progress! This game is not screwing around. It’s hard, grindy, and unforgiving. At least you can save anywhere. There are absolutely no save spots on the game, you just save whenever you want from the menu. It’s a small thing, but it papers over so many of the game’s problems. If you’re tired of the game’s general crumminess, just quickly save and come back to it later. It will be waiting for you, exactly where you last left off.

Once you’ve completed the challenge of figuring out what to do in the first world and then you’ve actually done it, you get to go inside the tower. It seems exciting. That tower has been teasing you for the whole game up to this point. You get inside the tower and, of course, it’s not as exciting as you hoped. One interesting thing you visit once inside the tower, outside of the four full-fledged worlds of the game, are the smaller one-room worlds you can optionally visit. They are indeed weird, as is starting to become normal for this game. One floor you encounter a small room full of palm trees and characters saying they live in paradise. On the very next floor you literally go to hell. Fire, brimstone, demons, people saying they are suffering for the Creator. What the hell is happening with this game?

Like I said you have four main worlds to try and clear to continue going up the tower. Good luck, because the game is very ornery about how it informs you of what to do next. There’s no world building, no setup to anything. You talk to someone and they tell you AIRSEED IS HIDDEN ON AN ISLAND. You want to ask them why, you want to ask them what Airseed is used for? Since this is an old RPG everyone only has one line of dialogue. So the only way to get more information is to have multiple characters to talk to. So you talk to another character. DID YOU KNOW THE CHARACTER NEXT TO ME KNOWS WHERE AIRSEED IS? You don’t say! So the only way you can make any progress is by exploring every nook and cranny of each world. While you explore everything, you will get very familiar with the monsters of the game. They all seem to come from the same lineage as the Final Fantasy enemies (Western-style fantasy like Dungeons & Dragons with Asian folklore thrown in for good measure) but their pictures all have something off about them.

The zombies look like they have a beret. The goblins who should thematically look puny because they are the first enemy of the game instead look like the most menacing enemy of the whole bunch. Magicians look like real-life sawing women in half magicians. All the insects have a cronenbergian-je-ne-sais-quoi about them. Thankfully, human-looking enemies don’t drop meat for you to feed your monsters; a smidge of restraint in a game with so little.

In aggregate, battles are not that interesting either. You are usually underpowered on your first time through the game due to the seeming randomness of everything and have a very frustrating time with battles. When you suffer enough of the game’s bullshit you can get familiar with its systems. It is then very easy to get overpowered and thus have nothing to do but press A over and over again without any cause for concern. There’s no middle ground. It’s either too hard or too easy.

You beat the boss of a world, get a sphere to unlock a door and climb the tower again. I don’t really want to go into too much detail. If you have the patience to endure the game’s harsh systems, give it a try. I could only play through the game again in short 15-minute play sessions. The game is infuriating and nonfun to modern sensibilities. You need to put a lot of your expectations aside but if you listen to what the game has to say, you will feel melancholy, sadness, bereavement. It threads on the sad part of the emotional spectrum and you’ll start feeling that those tiny little 8-bit characters have gotten a bum deal in life. Stuck in weird degenerate situations not understanding their whole life is the plaything of an idiot with a top hat.

Another important thing that will have an impact on you is the music by famous Square composer Nobouo Ouematsu. There are moments that are shockingly emotional, where a tertiary character would die or a situation would be resolved and a track full of melancholy would start playing and keep playing until you left that specific world and went back to the tower. It was heartbreaking and it was on Game Boy. It’s truly unique.

The End

You’ve cleared the four main worlds of the game, gathered the orbs and you face Ashura, the final boss. You defeat him, continue on the path up the tower and fall into a hidden pitfall! You fall all the way back to the first world, in the first town near the tower’s first door. All the important characters you encountered during the whole game are somehow all down here, sharing small moments with you. Next to the door of the tower, the man with a top hat you have seen multiple times. He taunts you one last time with the tale of paradise being at the top of the tower. You go back inside and climb the tower again. This time, you seem to take a different path and climb the tower from the exterior instead of from the inside. It’s fortunate; it means you don’t have to go through the exact same rooms twice. You face stronger versions of all four world bosses, again, and reach the top, again. You open the last door and you are presented with your reward: paradise! But there’s something wrong. There’s nothing here. A chair here, a tree there but nothing else. You explore the small white room, and suddenly you find the only character here. It’s the man with the top hat! He’s on the other side of a bridge over a river, and behind him is a door. You talk to him and he is now identified by the game as the creator. He congratulates you for being the first to complete his game. He explains that he created the tower and everything to test people for courage. You characters are appalled that he even made Ashura, this game’s version of the devil. He’s happy to see your display of courage and offers you a reward: one wish. Your band of characters is furious, pretend they did not climb the tower for a crummy reward (they totally did, they wanted to reach paradise!), and basically challenge the creator of their whole universe to a fistfight.

Now if you thought that was crazy, here’s really cooky: the creator can be killed in one attack with the saw. The game has this weird weapon called saw; it was meant to one-shot any enemy under a certain defence value, but due to a mistake by the programmer it kills any enemy above a certain limit. So all the strongest enemies can be one-shot by this weapon, and if you figure it out it can really help you get through the game. I did when I was a kid, which meant that I used the saw on the creator and one-shot him. Anticlimactic.

You are then shown your gang making their way to the strange door behind the creator, but they decide against going through and just leave to go back to the first world. Why would someone not open that door? You just killed god and you decide not to check out his super secret stuff! Some mysteries are best left unresolved according to the game. I beg to differ.

The ending of the game is absurd, it’s inarguable. But if you experience it for yourself, it will leave you with strong feelings. I readily accepted it when I first played the game: there was in my mind no crazier way to end a crazy game.

Conclusion

As I write this article, I’m on a big Goldeneye binge. It has somewhat changed my point of view because I originally intended to say that The Final Fantasy Legend was the only game I had when I got it. Replaying Goldeneye made me realize that Legend was my only Game Boy game I had to play through. I had a N64 when I played it, I had a PC with which I devoured Red Alert and Diablo. The Final Fantasy Legend was thus enshrined within those experiences and came out a sad, unique game making you feel melancholy. Not bad for a 1989 RPG I played in 1998.

Earlier I mentioned that I bought this game to start from the beginning and make my way from there, intending to play Final Fantasy Legend 2 & 3 later. Truth is the first game in the SaGa series did not convince me that I should play the subsequent games. It’s a shame really. I’ve played a bit of the second game, and Final Fantasy Legend 2 plays like the good memories I had of the first one. It’s not as obtuse, not as barebones. It’s more rounded and you’re having an easier time figuring it out. With only the experience of the first title, I don’t fault my eight year-old self from moving on to Final Fantasy Adventure instead.

Finally, I think that the game was essential to the community of Game Boy developers. It showed everybody a game on Game Boy could be as deep as an NES one, only your smaller team and budget forced you to compromise. For that it is essential.