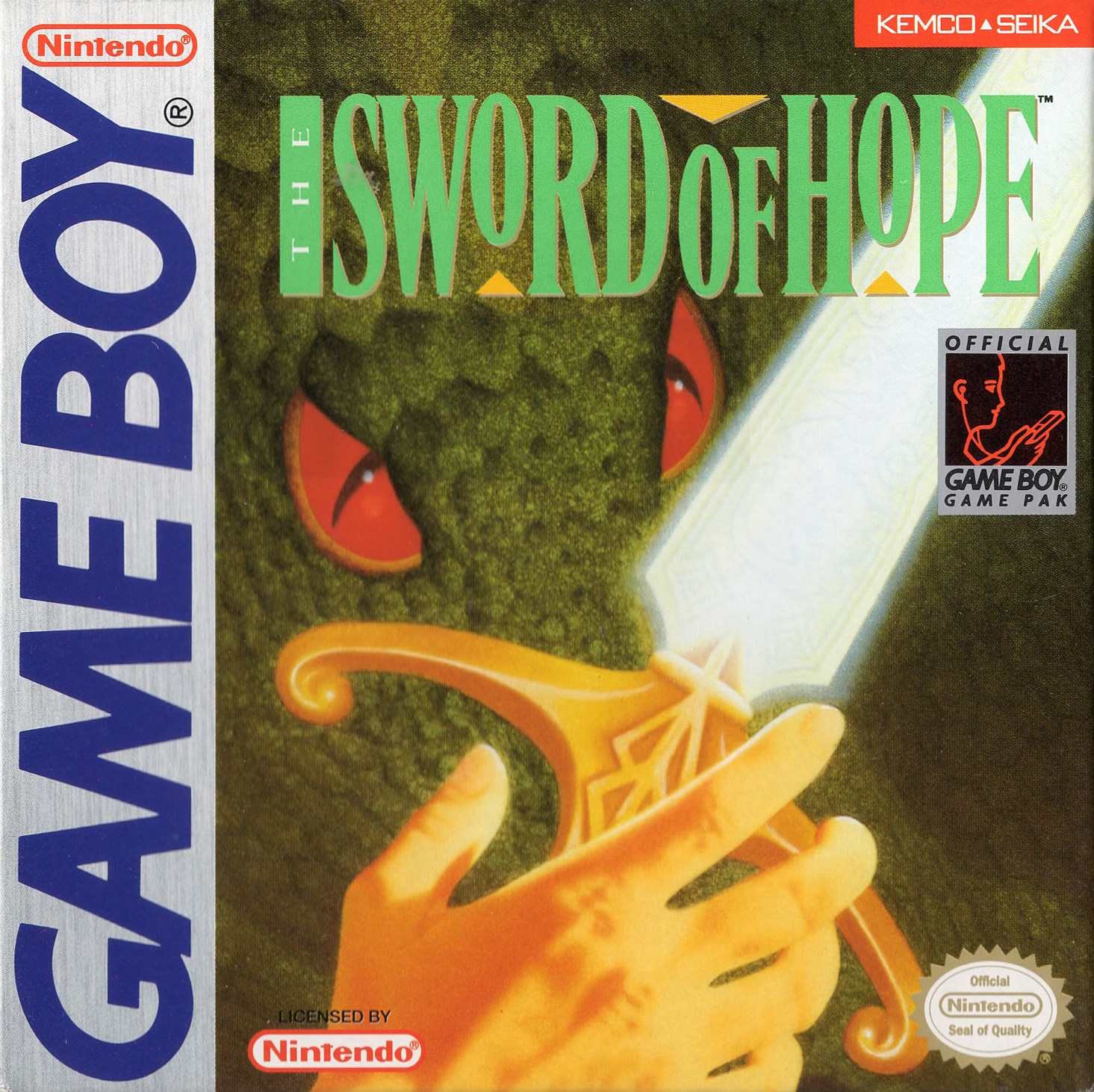

The Sword of Hope

- Japanese release in December 1989

- North American release in June 1991

- European release in 1991

- Developed by Kemco

IAKESOCMEK

I’m happy I experienced The Sword of Hope, even if I could not find the energy to finish it. It’s really unique. It’s a game I knew next-to-nothing about and that I’m now fascinated by. The Sword of Hope was made by Kemco who had just ported the MacVenture games to Famicom and NES. They had obviously intended to make a game in a similar vein but with a battle system lifted straight from Dragon Quest. They did not hit a gold vein: it’s reasonable for an early title on Game Boy to be this experimental but peanut butter and jelly it ain’t. The mix of RPG and adventure game just fundamentally did not work. Looking at a game that tries its best but does not work is still valuable and essential. Like Nuts and Gum.

Like Nuts and Gum.

Adventure Games Primer

Back when The Sword of Hope was released in Japan in 1989, adventure games had evolved into a very specific genre of video games but they were still at the core the evolution of text adventure games. Games like 1980’s Zork I allowed you to wander and interact with a large world through text alone, and as computers became more powerful developers had the brilliant idea of replacing the descriptive text with images. A new genre, called adventure games, was born that used graphics but still allowed the frustrating experience of text input for any interaction:

> pick up sword

I DO NOT KNOW WHAT "up" IS

> pick sword

CANNOT "pick"

> take sword

YOU PICK UP THE SWORD. WHAT DO YOU DO NEXT?

> go to hell !!!

I DO NOT KNOW WHAT "to" IS

>

Available on home computers, an expensive luxury at the time, with the best graphics out of any other game type, adventure games were using the limited PC technology to great effect. They also featured a newfangled thing that few other games had: a story. Compared to what is available today, this was laughable but do not dismiss the appeal of having a king give you your mission as you are playing the game. We take it for granted today but in the early ’80s having the story of the game unfolds as you are playing was a luxury reserved for the most dedicated video game players who could afford an expensive computer. NES players were stuck reading the manual to get a game’s story in the early days of the console.

By 1989, adventure games had moved away from text entry for every action and embraced menu-based interfaces. This was thanks in large part to Enix’s Yuji Horii. In 1984 he made Hokkaidou Rensa Satsujin: Ohotsuku ni Kiyu for the NEC PC-6001, a Japanese 8-bit computer. This was the sequel to his previous game, Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken which we usually know in the West as The Portopia Serial Murder Case. Horii did not like the text parser of adventure games and so replaced it with a menu-based command system. It basically presented you with every verb in the parser from the get go, eliminating the guesswork of what words to use. His team was then tasked to port The Portopia Serial Murder Case to the Famicom Disk System. They replaced the complex text entry of The Portopia Serial Murder Case with the menu system of its computer sequel thus bringing the genre into the console space in very successful fashion. Westerners might dismiss the importance of this; don’t fall into that trap. We might have never gotten Hokkaidou, Portopia or the myriad adventure games that followed in their footstep on Famicom Disk System but this is because localizing them was never envisioned, not because those games are unimportant. Horii would use the lessons learned with Portopia for his next project: the seminal role-playing game Dragon Quest, a game of dizzying influence. With Dragon Quest, he basically did the same thing he did with Portopia again: he simplified the gameplay systems of a western genre, this time the role-playing game. Before Dragon Quest, RPGs were usually a complicated, text-heavy affair. Think of a video game spreadsheet. Horii and his team got rid of anything that wasn’t absolutely necessary and made it easy for the player to understand what was happening. He also gave the player only a slight setback when they died; you only lose half of your money, and you’re brought back to the starting point of the game. This style of RPG referred to as the Japanese RPG or console RPG, is fundamentally the same to this day.

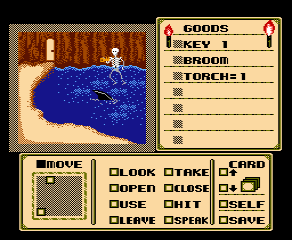

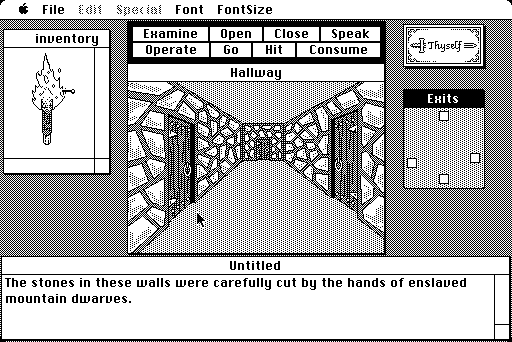

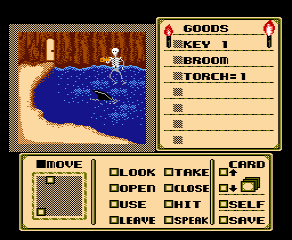

Amongst these exciting times of new genres being born and iterated on, we have Kemco Sekai who was carving its own slice of the Famicom adventure genre by porting the so-called MacVenture games starting in 1988. Released by ICOM innovations on the Macintosh starting in 1985, Déjà Vu, Uninvited and Shadowgate were some of the most innovative adventure games of their time. They used the Macintosh’s mouse, which meant you dragged the items in your inventory, clicked on your selected actions, and used a minimap to travel around: they were very forward-looking games with a lot of tactile feedback that took Yuji Horii’s innovation another step forward.

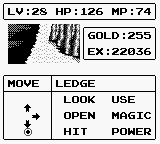

They were also incredibly unfair, killing you for the slightest of mistakes. This is not a joke, if you forget to relight your torch in Shadowgate, when it extinguishes, you’ll break your neck in the dark and die! It is obvious that The Sword of Hope owes a great deal to the Kemco port of Shadowgate on NES, the fantasy game in the series. It has the same minimap concept, the same vibe, and a very similar interface. It just has a Dragon Quest clone bolted on top of it.

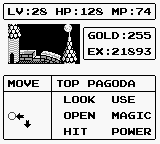

RPG Through and Through

I’ve talked a lot about The Sword of Hope’s adventure lineage but you really spend three quarters of the game playing an RPG, not an adventure game. Its adventure game lineage might be somewhat convoluted but its RPG roots are dead simple to understand; it’s just a copy of the first Dragon Quest. I could go on and on about the spell list or the statistics but there’s nothing to say. They took Dragon Quest, added more redundant spells and allowed you to fight more than one enemy at a time. Its close proximity to Dragon Quest brings me to one of my pet peeves with the Game Boy library: I can’t find an original mainline RPG. I don’t mean that RPGs on the system are bad but they all have something eccentric about them. When I mean mainline, I’m thinking classic Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest or Final Fantasy IV on SNES. Very R-P-G. High-fantasy setting, straightforward combat systems. On Game Boy, I can’t find anything original of that exact style. I’ve previously talked about the madness of The Final Fantasy Legend (the sequels are just as crazy). Lufia has procedural dungeons that kind of spoil the fun. Pokémon is Pokémon. You have the first three Dragon Quest titles, but they’re not original Game Boy games. And Great Greed, oh boy, let’s not even broach Great Greed. Does this look like the work of a team that finished the artwork?

Does this look like the work of a team that finished the artwork?

I was surprised to find that there’s a normo RPG hiding underneath the adventure game veneer of The Sword of Hope. But there’s an adventure game veneer, so I’m still not satisfied in my desire for a mainline RPG on Game Boy; the search persists.

But the RPG that The Sword of Hope offers is terribly boring. I guess that’s the problem with an RPG with so few choices to make; when your options are attacking or a spell that basically amounts to the same thing, without any variation in enemy type, battles have no meaning and turn into a numbers game. Can you get to where you need to go before you run out of HP, MP, and recovery items? If you grind long enough, you invariably always can. There’s no agency, you’re just pressing the A button until you’re bored. The question becomes whether you can suffer through all the grinding. As I’m getting older, the answer becomes no more often than not. I do not have the energy and time to waste on this. I can’t grind and grind and grind because someone in 1989 decided that was how an RPG worked. So I’ve decided halfway through the game to just punch in an end-of-game password and try my luck from there: Salvation?

Salvation?

But it’s not very helpful; while you don’t have to worry about fights and you one-shot all the enemies, you still lose an inordinate amount of time in battles. Enemies are represented with dots on your minimap and if there’s a dot in the direction you want to go, you will have no choice but to fight a battle instead of moving. So you could be stuck for 5–6 battles on the same screen trying to go north. Had they simply changed it to forcing a battle after your move it would have made it completely fine. So even starting from a fully decked-out save and walking to the end boss, knowing what you need to do to get there is still an unbearable chore.

Which I guess teaches me (and you) a very important lesson about games: don’t stop the player from doing what they want to do. Punish the player if you must but putting a randomized roadblock in front of your audience only serves to disengage them. You lose any interest quickly when you try six times in a row to go south but you end up in a battle instead, however easy the battles are. Imagine the developers knew their battles were boring; could they have simply removed them and shipped an adventure game? No, the game would have been too simple. There’s no real puzzle in the game, nothing much to do except figuring out the routes and what thing to interact with. So the RPG elements are an essential part of the game, no matter how boring they are. I can imagine the developers knowing they didn’t have a champion on their hands but still pushing forward, knowing that this early in the life of the Game Boy, a subpar title could still be very successful. They had done exactly that a couple months before with Mickey Mouse/The Bugs Bunny Crazy Castle.

What?

To top off how boring the RPG part of the game is, the text is poorly translated from Japanese. I definitely believe that the translation was made by a non-native speaker. Sentence structures are weird, word choices are sometimes strange but this could all be explained by limited character space. The thing that confirms we have a second-language translator are the jokes. They’re obviously the work of someone with a limited grasp of how English humour functions. For once with the Game Boy Essentials project, I can say something as a true professional: I have a degree in Second Language Acquisition, specifically English. And this game is at the language level of one of my first year student trying their best. Definitely not on the level of a professional translator, even on their worst day.

Conclusion

Maybe someday in the future I’ll forget the brain-dead battles, revisit it and finish it. For the time being, I’m happy saying it is essential without saying you need to finish it. You just need to try it out a bit to understand its flaws and why they make it so boring to play for more than a couple of minutes.

This article was first published on the .

This article was last modified on the .