Donkey Kong Land

- North American release in June 1995

- Japanese release in July 1995

- European release in August 1995

- North American release in 1997

- European release in 1997

- North American release in November 1999

- Player’s Choice Re-release

- Japanese release in March 2000

- Developed by Rare Ltd.

Monkeying Around

Donkey Kong Land is the worst case scenario. All the mistakes a team can make when adapting a concept to Game Boy, they’re all there. Dark backgrounds? Check. Overtly busy sprites? Check. Leaps of faith level design? Check. Poor physics? Check. If you want to know how not to make a Game Boy game, look no further, this game has done everything wrong!

With their SNES game, Rare was able to convince everyone that a polygonal game was running on the humble Super Nintendo hardware. With the Game Boy adaptation, they revealed their monkey antics. LOL.

I got Donkey Kong Land in 1995 when it was released, so it’s one of those games where I’m super critical because I’ve owned it for 20 years. When I was a kid, it took me days to understand what the KONG letters you collected were supposed to be. Not as a concept, I mean as an object. I didn’t know what those squares were! Were they TVs? Candy? I couldn’t decipher them. Why? Because the game is simply too hard to see on an original Game Boy. I really love the SNES Donkey Kong Country games. DKC 2 is up there in the pantheon of eternal games. The Donkey Kong Land sub-series, not so much.

But people love this game. To those people I must say I’m sorry, I kind of liked it when I was a kid despite its flaws but the only thing essential about Donkey Kong Land is its myriad of flaws. They paint a much more interesting portrait than the few things it did right.

Forgetting About the Ghosts in the Machine

Let’s talk about Donkey Kong Land by discussing first what it was displayed on, the Game Boy screen. The shortcomings of the screen usually talked about are:

- It’s unlit;

- It’s only four shades of grey with a pea-soup green background.

But people always forget about a last shortcoming: the screen suffers from severe ghosting. What is ghosting? It’s a slow time to turn off a pixel when it was displaying colour before. When the Game Boy tells its screen to turn a pixel off, if the screen is displaying an exploding bomb for example, then the time to turn off that pixel is not instantaneous. So when a character is moving, as is the case with Super Mario Land for example, he leaves a trail of blurry pixels behind. That’s fine for Mario because he is small, surrounded by pixels turned off and you’re moving in a single direction, so that leaves a trail behind him. When he gets near an enemy or a wall, anything that produces ghosting of its own, the whitespace allows you to keep making sense of what’s on the screen. So it’s never too much of an issue.

At this point remember that no screenshot I can show you can display the ghosting the Game Boy’s screen suffers. It’s a result of movement, and you can only see that movement artifact on an original screen. My screenshots serve only to show what Rare didn’t do to alleviate the problem.

You might be tempted to think that only characters can cause ghosting, but everything that moves on the screen does. So when you move forward, or jump, or swim, or swing on vines the Kongs, enemies, platforms, background elements, barrels, bananas, basically everything clashes with everything else. This causes general ghosting and turns the screen into a mess of late pixels trying to catch up to a game too complicated for the puny screen: everything’s blurry. The processor and the graphics chip are fine, mind you, the game suffering no slowdown at all. It’s the screen who never catches a break. Any moving thing will create ghosting. Thus, you have to be careful when creating a game’s environment to keep it simple. To show you what I mean, let’s compare two games released around the same time: Kirby’s Dream Land 2 and Donkey Kong Land.

Kirby’s Dream Land 2 and Donkey Kong Land.

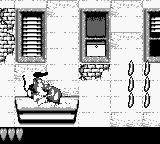

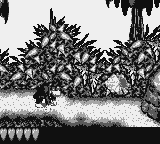

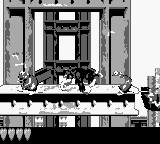

On the one hand, Kirby uses its art style and restraint to show a vibrant, dare I say colourful world while keeping a healthy dose of whitespace to keep the ghosting out of the way. Objects have shapes, but are not coloured when you can move in front of them. They have borders, but not patterns. I’ll grant you that the grass is borderline, but there the game relies on Kirby’s whiteness to prevent an excess of ghosting. Truly great developers like HAL Laboratory knew how to push the limits of a piece of hardware, but not exceed those limits. Donkey Kong Land, on the other hand, is not Rare at its best. This is the worst of early 80s Rare. When they made dubious games for ZX Spectrum. It has no sprite borders and a busy background and is thus a blurry indecipherable mess.

If you look at a picture of the game, you’ll see what I mean when I talk about an undecipherable mess. It takes you an extra moment to process what you’re looking at. Observe carefully a screenshot of Donkey Kong Land and think on what your brain has to do to decipher what you’re looking at. I don’t know about you, but I can feel the gears turning in my head trying to understand what’s happening and that’s without ghosting. Now imagine that everything is moving at 59.7 frames a second and blurry. And green. Can you spot Donkey Kong in that picture? Now try it on a Game Boy screen.

Can you spot Donkey Kong in that picture? Now try it on a Game Boy screen.

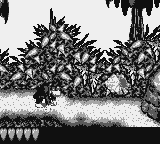

You might argue that the game features different environments and that we should also look at the other type of backgrounds. You are correct. The first set of levels uses the jungle tileset, the worst of the whole game in terms of readability, but believe me the others are not much better. Why? Because there still is no respect for what the screen can’t do right. See for yourself.

You have some breaths of fresh air in there but most of the game’s art style is simply too complicated for Game Boy. Now that we’ve completely tarnished the game’s art style, I feel I need to remind you I love Rare’s Donkey Kong games on SNES. A very appropriate art style of pre-rendered graphics for a system that could handle the load. Unless your TV was somehow a Game Boy screen. But I digress.

There is another thing we need to talk about that induces ghosting: the camera. In a 2D side-scrolling game, you need to build a movement system for the camera. You cannot just directly map camera movement to character movement. Play Super Mario Bros. and look at how the camera establishes boxes for Mario to decide whether the screen will move or not. I could go into detail about how the boxes in Donkey Kong Land work but suffice it to say they’re all screwed up! I can talk of one telling example.

There is an unnecessary camera move upward when jumping while standing still. It is one of the many ways the camera causes undue ghosting. Other games will prefer large, generous camera boxes that will allow you to reach nearly to the top of the screen before scrolling. It’s a choice with consequences (you can see less of what’s above you) but Rare chose the wrong priority here.

Bad Intentions

So what were the intentions of Rare with Donkey Kong Land? Obviously, they were on a mission to bring the CGI graphics of Donkey Kong Country, the revolutionary SNES game from 1994, on the tiny Game Boy. They did, but was it worth it? When it was released, Donkey Kong Country was a revelation. You can do 3D graphics on Super Nintendo? Of course the answer is they couldn’t. They faked it by building 3D models of everything on Silicon Graphics workstations. The developers at Rare then turned pictures of those 3D graphics into 2D sprites and tiles that worked on the SNES. When they planned and built a Game Boy version of Donkey Kong Country, they said, “let’s do the same thing!” Super Nintendo original next to the Game Boy bastard child.

Super Nintendo original next to the Game Boy bastard child.

You can see how the sprite of the Game Boy version is similar to the Super Nintendo original. They obviously started from those same 3D models built on SGI workstations and ran them through a process that made them into Game Boy sprites. While I would argue the final sprites on SNES are a tour de force, the GB sprites are a step backward. A technological process whose final result is not as good as giving every sprite a hand-drawn border. Keep in mind I’m showing you the best result of this process; the character of Donkey Kong, who was certainly given the most scrutiny. I’ve already talked about how bad the result were with the background tiles.

I’ll quickly address one other issue: screen crunch. A common complaint against Donkey Kong Land is that the sprites are too big for the tinier screen of the Game Boy. Well, the SNES has a 256 pixels horizontal resolution. The Game Boy? 160 pixels. Donkey Kong on SNES is 40 pixels wide, so to be the same proportions he should be 25 pixels wide. DK on Game Boy is 27 pixels wide. So no, the sprites are not too big. They’re similar in proportions. Rare made all the sprites size appropriate. However, when people complain about the size of the sprites they are simply pointing the finger at the wrong culprit. You see, like we discussed earlier, Rare messed up the camera system. Donkey and Diddy end up in the middle of the screen when moving or even worse, on the right side of the screen when rolling. So you never see what’s coming. You end up having to make tons of leaps of faith, not knowing if there is something on the other end of your jump, and when you’re running or rolling you have no reaction time. Your nose is too close to the action even with size appropriate sprites. Donkey Kong Country on SNES had no such problems.

A Game for Super Game Boy Perhaps?

I cannot shake from my mind the idea that after looking at all of these quirks and faults that the game was built primarily for the Super Game Boy. I do not know how development kits for the Game Boy worked in 1995, but I would bet money most testing was done on the Super Game Boy, not the original Game Boy. There’s no ghosting and the colour helps with the characters and background. But even with the Super Game Boy they bungled it. Read Christine Love’s article on Donkey Kong and Donkey Kong Land to see how even if they might have built the game with the Super Game Boy, they didn’t do anything right.

Saving

In my Tetris article, I talked about how important it is that Tetris features no saving but all the progress is in you, and how that is super cool. In Donkey Kong Land, you can’t save the game unless you gather all the KONG letters in a level. You want to save, you’d better get through a level you know well and find all those goddamn letters without losing all your lives. It’s super dumb and unfair. If the game was a masterpiece, this would be a travesty worth decrying. Here, because everything else is so wrong, I just mention it and move on.

The Music

Let’s end this on a good note. Graeme Norgate and Dave Wise made very good music for that game. They mostly use the soundtrack of DKC as a springboard to do something different that recalls the original tracks. I like it. I was playing DKL on my AGS-101 and found the music lovely. Then I switched to my original Game Boy and realized how finely tuned the music was to the speaker of the DMG-001. It’s good work worth mentioning. It really comes alive on original hardware.

Conclusion

I’m sorry if you liked Donkey Kong Land as a kid. I don’t know what kind of eyesight you have but I couldn’t see squat back then and I can’t see squat today. That’s why it’s essential. It’s what not to do when adapting a concept to Game Boy.

This article was first published on the .

This article was last modified on the .