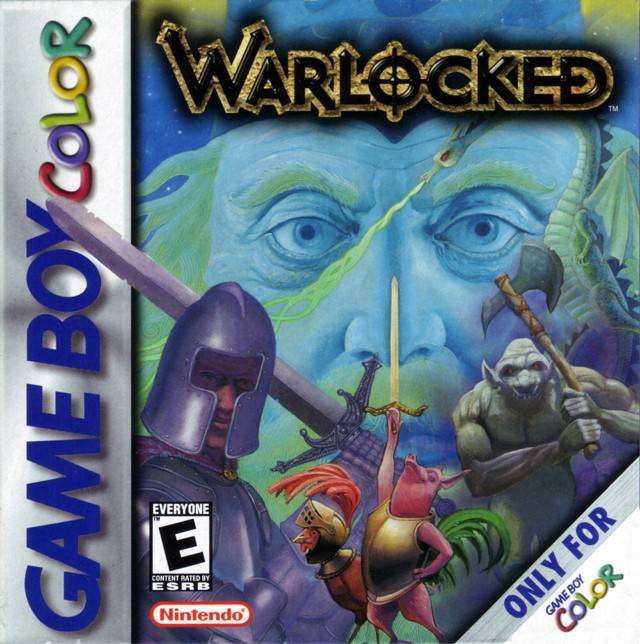

Warlocked

- North American release in July 2000

- Never released in Japan

- Never released in Europe

- Developed by Bits Studios

Portable Marvel

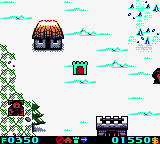

Warlocked is one of the reasons I started this whole project. I always wanted to talk about it. It’s an impossible feat; a real-time strategy (RTS) game on Game Boy Color, filled to the brim with charm and delight. The game has so much gumption to achieve so much with so little that you will be filled with awe. Warlocked is the quintessential essential game.

Let’s Describe the Game

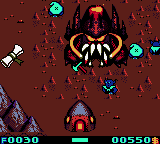

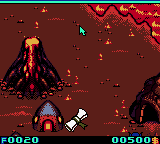

Warlocked is obviously inspired by Warcraft’s aesthetic, but it has its own artistic merit aside from its inspiration. A game clone might have some original aesthetic, but then you load a new level and everything suddenly looks like they should be sued. Warlocked is not like that; it has its own style from beginning to end without falling into the pitfalls of being a clone. They copied Warcraft’s premise of a fantasy RTS of Orcs fighting Humans but not much else. As an example, the orcs in Blizzard’s Warcraft live in round mud houses in a rustic world of mushrooms and green water. The orcs in Warlocked live in hell!

The game is a real RTS, with a top-down view and cursor controls to order your units. It has a rudimentary control scheme, a rudimentary economy, a rudimentary tactical system. You get my point. Everything is barebones, but you cannot fault the game, it’s on Game Boy Color.

I have always been a perennial RTS player, so you’ll forgive me if I speak gibberish when talking about the game. Warlocked uses the first Warcraft ruleset as a template. This means it has two artistically different factions that are nonetheless identical in terms of abilities. It also means that you mine two resources: gold and wood/mountain (?) in exactly the same way Warcraft does it. These resources are gathered and brought back to your castle by workers. The castle is your central building that can produce more workers. In a breach of the Warcraft ruleset, the central castle is already built on every map you play, and cannot be rebuilt if destroyed. It’s immediately Game Over. The fact this building cannot be built and is placed ahead of time is a limitation for the sake of simplicity. Think of every situation that cannot happen because your main building is already placed and cannot be replicated.

I’ll talk about more details later on, but just keep in mind that the game is legitimately an RTS. You choose your campaign, go through missions that slowly teach you the concepts and in just a moment, you’re training warriors in your barracks, exploring the map, achieving objectives, defending your base, all while micromanaging your resource gathering.

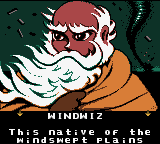

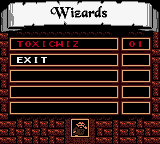

Surprisingly, it brings some fresh ideas to the RTS concept. First, you have dragons, the strongest units of the game and the only flying units available. They cannot be built. Instead, you find their eggs on the map, they hatch and you bring the baby dragon back to your base. The dragon matures after a short while, and you get the dragon. It basically is capture the flag with the reward being a wonderful flying unit to smite your enemies! During single player its impact is nothing fancy, but it brings some much needed tactical complexity to multiplayer matches. Oh yes indeed, the game has multiplayer and it works perfectly well! With two cartridges, you can have a ton of fun! The second idea is related to a second multiplayer mode, based around a kind-of deck building concept. Whenever you finish a single player mission, your remaining resources are put into a pool that you can use to create armies. Those armies can then be compared against other players, using the Game Boy Color’s IR port. I never was able to experience the feature since I never knew anyone who owned the game. The last idea of the game is wizards. Throughout the campaign, you will meet an assortment of unique units. They’re somewhat hidden in the maps, and once they are found they join your army, and they each bring a different spell to help you. Some have passive spells, like stronger armour for all your units, while others have active spells, like turning enemy units into chickens. They all have dumb names to accompany their spell that end in -wiz, like Chickenwiz and Quakewiz. You can have a maximum of two wizards out in battle at the same time, which means you have to choose the spells you want wisely. Once you complete a mission, if the wizard survived, they join your permanent list of wizards and they can be reused in future single-player missions. It’s obviously inspired by Pokémon, but be careful: if they die during a mission, they’re gone for good. You can replay missions to go and get them back, however. Which means you can actually have more than one copy of each wizard. Just like Pokémon.

The best part of the whole idea is they’re usable in multiplayer matches. So you can show off and use your wizards when playing against another player. I’ve played Warlocked multiplayer matches only once in my life (thanks, Mark Weissfelner). Clowning your adversary with your wizards was the most fun I had playing this game and I only managed to do it once. Drat!

You also need to trade your wizards if you want a full set, since you cannot acquire all the different wizards with one cartridge. The trading happens over IR, just like with the armies. I have to say, this whole IR thing is bugging me. Since the Game Boy Advance did not have this IR port, it makes it awkward to test features when you only have Game Boy Advance systems (I happen to only own one Game Boy Color at the moment). Not a fault of the game, but an unfortunate problem for me, since I’m a Game Boy Advance SP hoarder.

Learning About the Game

I have loved Warlocked from the word go. While all my friends had moved on from the Game Boy after the craze of the first Pokémon game, I stayed invested in buying and playing Game Boy titles. I had always been there, really. Between 1990 and 2001, I never stopped procuring Game Boy games. By the late ’90s, I was visiting the few websites I knew who covered Game Boy releases. One website I remember is IGN, who seemed to have assigned one person to cover the Game Boy: Craig Harris. I would connect to free ISP Juno using a bugged version of its software that meant I never saw its intrusive ads (that’s a hell of a story for another time), and going on IGN to see if they had any Game Boy-related news. From the first moment I heard about Warlocked, I knew I had to buy that game. I hoped that my local Zellers, my only source of Game Boy games, would stock the game when it was released.

IGN has slowly devolved to the point of inanity, but it still has articles from its heyday available if you use an external search engine to find them. I found two pages from 2000 mentioning Warlocked. Rereading those articles on IGN raises many questions about the development of the game. Why don’t I ask some of the developers?

Highlighting the Workers

Looking to be original on the platform is inspiring, knowing you’re breaking new ground as a developer is a key motivation, and drives you to do the hard work necessary to achieve something unique. I don’t think anyone else attempted to do what we did, the game was one of its own on the platform.

— Dylan Beale, producer of Warlocked

I gathered enough courage to reach out to Dylan Beale, the producer of the game originally from Bits Studios, to answer some of my questions. Even though we are in the midst of a pandemic unlike anything modern society has ever seen, he found the time to patiently answer my questions. I feel so elated to have talked to the producer of one of my favourite games. He even, without me ever asking, roped in Steve Clark, the programmer of the game to answer my questions too.

I was curious about how they had the idea to make an RTS on Game Boy Color. I asked Dylan Beale how the idea for the game came about:

Dylan: People were playing a lot of Warcraft 2, it was really popular amongst the staff, and naturally when you’re thinking of new game ideas you can’t help but be inspired by the games you’re loving to play at that moment.

I’m happy Dylan didn’t beat around the bush: Warlocked is unapologetically inspired by Warcraft. It has its own ideas, particularly with regards to the music and the gameplay, but the game proudly wears its inspirations on its sleeves.

Answering the same question, Steve Clark highlighted how he was convinced of working on the project by a clever technological solution.

I first heard about the idea of doing an RTS for the Game Boy Color in a meeting with Foo Katan (the owner of Bits Studios) early in 1999. I’d gone in to discuss potential Game Boy Color work and he mentioned the design Martin Wheeler had been working on. He had me completely hooked by an idea for how to get around the classic sprites on a line flicker issue when handling the sixteen by sixteen pixel sprites, which was to write them into the background map whenever they were suitably aligned.

— Steve Clark, programmer

That’s how you convince people that your idea is good: you elegantly solve difficult problems for them.

The problem he’s talking about his fatal to an RTS on Game Boy Color. The system cannot display more than 10 sprites on the same row across the screen. It’s a hardware limitation of its display chip, there’s no way around this. For those who don’t know, a sprite is an element that can freely move around the screen. The enemies and characters in Mega Man are all made of sprites, for example, while the elements that stay solidly stuck to the background grid, like platforms and ladders, are not sprites. To further complicate things sprites are only eight by eight pixels in size on Game Boy. Most games use characters much larger than eight pixels. To make larger characters developers simply put multiple sprites next to one another to assemble characters of multiple sprites. This allows them to make characters the size they want but means the sprite limit is much tighter. In a platformer like Super Mario Land, you can design your levels around the limitation. You can place enemies within your levels so the player has very few chances of encountering more than the sprite limit, amongst other things. With an RTS, you’re screwed. The player can move a large number of units wherever she likes. If the player wants to make a line full of workers that forces the console into an impossible display scenario, she can.

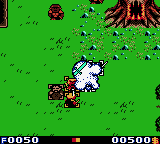

Since every unit in Warlocked is made of a grid of two sprites by two sprites, it would mean that you couldn’t display more than five units in a row. But the game is able to display five units in a row nonetheless. How is it possible? This is where Martin Wheeler’s idea comes into play. Whenever characters are immobile, they are turned into background tiles. They transform from an element that can move freely around the screen to a part of the scenery. You would not be able to see this, since there is no visual difference between a sprite and a tile. The switch from one state to the other is invisible. Your units are intrinsically connected to the background, but that’s not a problem. That’s exactly what you want anyway. You’ve ordered to stand still. You can see that when units are moving, and are therefore not tiles, you can hit the sprite limit. Here, the limit is broken and the game stops displaying the bottom half of one unit. Other games might choose to flicker the sprites. Programmers decide exactly what happens when you reach the sprite limit.

You can see that when units are moving, and are therefore not tiles, you can hit the sprite limit. Here, the limit is broken and the game stops displaying the bottom half of one unit. Other games might choose to flicker the sprites. Programmers decide exactly what happens when you reach the sprite limit.

Making a Game Boy Color title

I’ve often wondered how much time a Game Boy title took to make (I guesstimate at least six months), so I asked both of the guys what they experienced.

Steve: All told the game took a little over a year from start to finish. My projects were quite varied even then, so there was no typical length as such.

Dylan: Wow, it was a long time ago. It took longer than R-Type DX, but that was a port, although quite a challenging one. Creating a unique IP always requires more time, and Warlocked was technically challenging with its AI pathing and having many units on the screen. We would have been driven to finish by the budget, and often having a strict timeline pushes you to make creative and technical decisions, so as a function it’s positive. What the budget did do was make the team work very hard to get it out!

Their answers are very valuable. They had budgeted for a year, and that was that, because that’s what the project needed and could afford. I don’t think many Game Boy Color titles would have a very different experience from theirs, since the Game Boy was well suited to straightforward development. Dylan mentioned the challenges of bringing an RTS to Game Boy, and he gave me more insights.

Dylan: The hardest programming challenges were getting the game running speedily enough, trying to ensure the AI (whether in terms of pathfinding or defending a unit’s own position) was capable enough, and, of course, multiplayer.

So Dylan mentions several specific issues that he faced while developing the game, and he then quickly went into further details for each one.

The enemy AI was fairly simplistic, in that the units could manage to defend themselves or choose to attack, but this simplicity allowed for the game to play quickly.

I’ve talked about this before and I’ll mention it again: the Game Boy cannot do convincing AI. It just doesn’t have enough RAM and CPU speed to achieve complex enemy behaviours in real time. Warlocked met the same fate: as Dylan clearly says, the AI had to be simplistic for the game to exist. In fact, the enemy AI has only two behaviours:

- Attacking when detecting your units: When you move units within a certain range of enemy units, they will react by making a beeline to the unit who first made range and attack it.

- Spawning units and heading towards your keep: When you have been detected by specific enemy units, the pre-placed enemy barracks will start spawning units at a set rate and send them towards your keep. If they encounter one of your units or buildings, the first behaviour mentioned above will trigger. Those enemy barracks are always placed in a simple path from your keep, so the path-finding is never a problem. Speaking of pathfinding:

The pathfinding was the single biggest issue in the whole game. There are many ways to program pathfinding, but they mostly rely on both a good amount of memory to determine the best route and a fast processor to cope with the computations. The Game Boy Color’s processor simply couldn’t handle some of the best algorithms for multiple units, and so a best attempt system was used. Although far from perfect, it does manage to navigate itself away from a number of tricky situations, and allows units to move and act as a group with some success.

Be careful, dear reader, to understand the difference between enemy AI and pathfinding. While enemy AI is the behaviour of your enemy opponent, pathfinding is the movement behaviour of all the units in the game, enemy or friendly. When you click a destination on the map, it is the constant calculation of the route to take to that destination. It’s a notoriously complex computing problem, and there is no ceiling to the amount of computing power you can throw at those calculations.

Here, I have nothing but congratulations for Dylan and the rest of the team. The path-finding is constantly stumped and fails, but it does so in a very predictable manner. Units abandon when they can’t find an entrance through a wall, and the path-finding is usually OK when you give your units a destination within the same screen. It’s when you decide to traverse large distances or turn a sharp corner that the path-finding fails.

The game uses all sorts of tricks to alleviate potential path-finding issues like wood collecting. In a game like Warcraft, you have to collect wood. Workers will try to collect the wood tiles that are the closest to the lumber yard. In Warlocked, that was obviously too complex a behaviour to implement, so workers will simply collect wood in a straight line. It’s not ideal, but again it is a predictable behaviour that you can quickly understand and control.

Multiplayer was its own special sort of challenge, and ended up using a custom master/slave mechanism.

I can say that with the multiplayer, they succeeded. The game runs a bit slower, and the voice clips for the units are absent in this mode, but I’d dare say multiplayer is the greatest achievement of this game. A full-fledged multiplayer RTS on Game Boy Color. I own two copies of Warlocked just to be able to see it with my own eyes.

An interesting quirk is that the game completely stops whenever one of the two players goes to the wizard selection screen. It’s obvious they couldn’t run both the selection screen and the game at the same time.

The Control Scheme

When I asked Dylan about the challenges the game encountered, he mentioned the interface:

From the graphics and interface side, squeezing the control system into something that used just two to four buttons and the D-Pad was something that gave me a lot of pride. Without being too fiddly, it’s possible for the player to perform a vast array of actions without having to resort to cumbersome text menus, which would break the flow of the game.

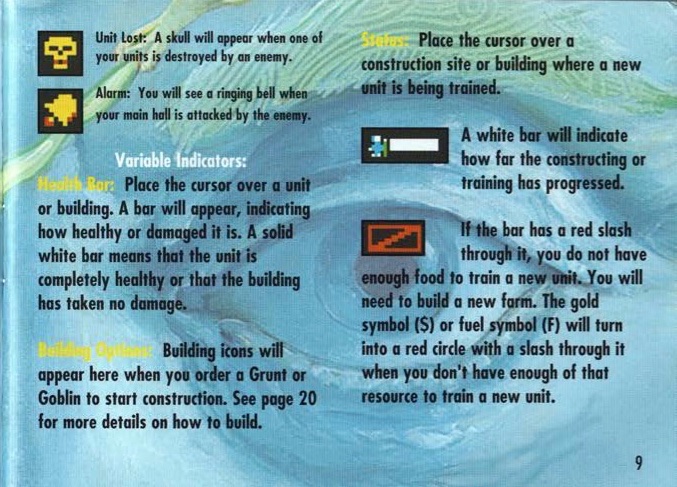

Let’s quickly address the game’s user interface. The game has a small black status bar at the bottom of the screen which has all the typical RTS information. Wood/Mountain and Gold amount are always present near the corners, and the middle of the bar features contextual information. The manual is pretty clear about the status bar’s functionalities.

The game’s controls are fascinating. The game manages to squeeze all the barebones RTS controls into a D-Pad and four buttons. It even manages to have some surprising features: guarding another unit, ordering the construction of buildings, and even unit control groups.

The controls start and end with the cursor. Managing to move it is unfortunately the clunkiest part of the interface; a mouse is much better for this purpose, but all we have is the D-Pad. You eventually learn to get by, particularly if you learn to hold the B button to speed up your cursor speed.

When you have no units selected, the cursor is a big hand. Whenever you hover over a unit, you can select it using the A button. Once you have selected the unit, you can order it on the map using the A button again. Holding the A button releases your selected unit, freeing you to select another one.

To train units, you simply bring the cursor over the building you wish to use, and you press A to start training. It’s easy as that. But wait a minute! There are two units that can be trained in the barracks: the warrior and the archer. How do you train two units with one button? You press A for a warrior, B for an archer when your cursor is over a barracks. They didn’t even need to implement a menu.

That’s the minimum amount of control systems you need for an RTS. Dune 2, the first significant RTS, has no functionality beyond that in terms of unit and building control. And in that game, you needed to select the movement action on the keyboard before performing it. Every time.

Warlocked thankfully goes beyond the bare minimum. Instead of pressing the A button, if you hold it with no units selected, you can select multiple units by drawing a rectangle with the cursor. It’s now a given that an RTS will allow you to select multiple units, so you might be surprised that I’m considering this above the bare minimum, but that shit had to be invented. Like I said previously, Dune 2 allowed only a single unit to be selected at once.

However, the unit selection comes with some caveats. There is no visual cue surrounding your box; it’s literally invisible. You also have a limited selection range. You cannot make a box larger than four units by four. This can be vexing; you can easily have fewer than 16 units, but spread over a much larger area than a perfect square four units wide. This makes it tiring to have to move each unit separately to fit within the small unit selection box. One thing that would help is a way to assign a control group, and surprise surprise, Warlocked can assign two control groups! This game has a feature that Warcraft II didn’t have at launch! Since you only have two buttons, and they’re already accounted for, what button are you meant to use? Select, of course. Pressing Select and holding the A or B button creates a group with your currently selected units. Afterwards, pressing Select will reselect your last control group, and Select with a quick press of A or B will highlight that group for you. I have to admit I never used the feature when I initially got the game as a teenager; the part where you have to hold Select to create a group always stumped me. Instead, I made units guard others in my army. That way all of my army could move together when I moved the units being guarded. It was clunkier, but that’s all I could figure out how to use.

The final order of business in the game is the worker. How do you build structures when all the buttons are so overloaded with functionality? The game reuses the B button and it works OK. Whenever you have workers selected, the game will display a construction overlay on the ground automatically. Pressing the B button will present a small menu in the status bar, where you can choose which building to build with the D-Pad.

Once that’s done, you’re good to go; your workers will take care of the rest.

The Music!

I implore you to listen to the soundtrack of Warlocked. The soundtrack is made by a composer known for his Commodore 64 work, Jeroen Tel, and it has that wonderful European composer quality that is so powerful on Game Boy. It has this interesting emotional undercurrent that really elevates the whole game. My favourite tracks are Lava 1 and Woods 1. I think I get this feeling because the game is trying something different from the usual understated Game Boy music. RTS music tends to be very preeminent; there’s a strong tradition in the genre of the music never taking a step back during gameplay. I guess we have Frank Klepacki, composer of Westwood titles, to thank for his active soundtracks. Warlocked does the same thing. It has an energetic soundtrack that draws attention to itself, by taking inspiration from Warcraft 2: Tides of Darkness. The soundtrack in that game is unforgettable and grabs your attention immediately. Warlocked goes for the same effect and I love it.

When I first bought the game as a teenager in 2000, I would start the music test on a track I liked, connect headphones to my Game Boy Color, put it in my pockets and walk to school listening to the music. I liked it that much.

Conclusion

I have to thank Dylan Beale and Steve Clark for their insights into the game. I did not feature every single quote they gave me in this article, but I learned a lot from their openness. They’re the first Game Boy developers I talked to, and I could never have hoped for a better duo. Thank you guys.

I guess I also have to thank them for making Warlocked! This game is such a wonderful curiosity, and it couldn’t have happened without all the developers’ sheer force of will. They made an RTS on Game Boy Color. And it’s not bad, far from it. You owe it to yourself to play it, it’s essential. Those guys shot for the moon and they actually succeeded!

This article was first published on the .

This article was last modified on the .