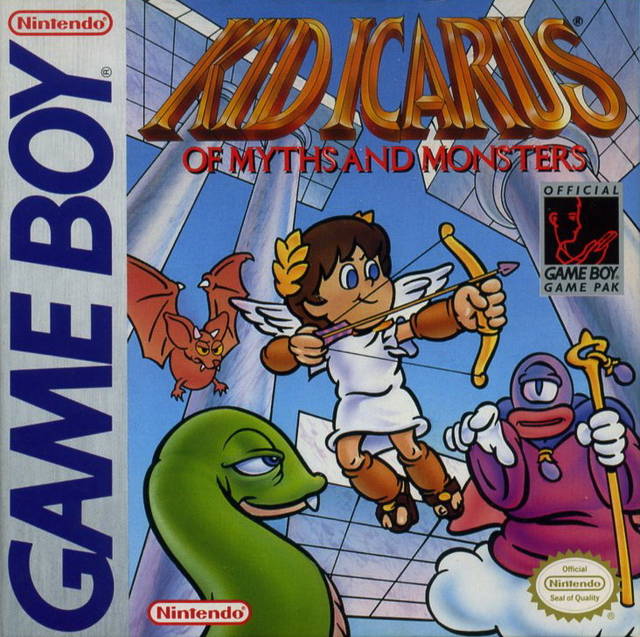

Kid Icarus: Of Myths and Monsters

- North American release in November 1991

- European release in May 1992

- Developed by TOSE

Not Kidding

Kid Icarus: Of Myth and Monsters can be a frustrating game. Bear in mind, playing it is not particularly frustrating. I’d argue Nintendo, collectively as a company, is the best video game developer stable in the world, so very few of their games are wholly frustrating. They have a strong company culture that focuses on exactly the right things. But games like Kid Icarus: Of Myth and Monsters are expertly made but lack any valuable contributions, and that’s why I’m frustrated. The choices the game makes are pedestrian; you’re left with a bittersweet taste after completing it, never reaching the greatness you hoped for. Even though it is expertly made by Nintendo with support from the shadowy TOSE.

Perhaps this development structure, of a Nintendo employee taking care of the design with TOSE delivering the programming under contract is why I feel underwhelmed. Metroid II: Return of Samus was also designed by the same person, Masafumi Sakashita, and I love that game. However, Metroid II was fully designed and programmed by Nintendo R&D1 developers with no outside work-for-hire. With both games designed at the same time Metroid II was clearly the primary project since they made it internally. This Game Boy sequel of Kid Icarus ends up a lesser work made with far less precious developer time. Let’s explore further the situations surrounding this lesser, but still essential, work.

An Angel in Context

For release in the fall of 1991, Nintendo R&D1 had two games under development that ended up released. Metroid II: Return of Samus was developed internally while they tasked Masafumi Sakashita Kid Icarus: Of Myth and Monsters with support from TOSE’s developers. Those games are interesting for how they are both different compared to R&D1’s previous Game Boy titles. After the initial games released with the Game Boy in the middle of 1989, the developers at Nintendo R&D1 made and released Dr. Mario, Radar Mission and F-1 Race in 1990. Those games clearly continue in the same vein as the earliest Game Boy titles made by R&D1. They are simpler pick-up and play titles without any save features that can be enjoyed during quick gaming sessions. By contrast, Metroid II and this second Kid Icarus game are both involved exploration games with a save function. To me, this reads as a pivot for the creators of the Game Boy. Before 1991 they developed and released tailor-made experiences for a portable console. They made a new puzzle game starring Mario (that they also released on NES), they made their take on the board game Battleship, and they made a small racing game showcasing a new four-player peripheral.

With their two 1991 games they were instead making faithful sequels to games that were made for NES but adapted for a portable context. Moving forward this would be the new normal on Game Boy. Case in point, 1990 was the year with the most puzzle game releases. Games moving forward would be more lounging on the couch waiting for dinner and less sitting in the bus waiting for your stop. In a sense this is Nintendo catching up to some prescient third-party developers who had already figured out how to make more involved games, with titles like Double Dragon, Ghostbusters 2, and Final Fantasy Legend.

Interestingly, Nintendo R&D1 would never again develop more than one Game Boy title a year after 1991. I believe their reduced output is due to their work on the Virtual Boy at the time. We know that by 1991, Gunpei Yokoi and the rest of R&D1 were already working on the Virtual Boy. Keep in mind, counting the cancelled games we are aware of, Nintendo R&D1 developers worked on at least ten games for the failed successor to the Game Boy. That’s enough to occupy a division for five years for sure. Adding on top of that the long, protracted, and complicated development on the Virtual Boy itself, it’s no wonder Yokoi and his team had little time to spare to develop Game Boy titles between 1991 and 1995. I can’t shake the feeling playing Kid Icarus: Of Myth and Monsters that I’m playing a game that R&D1 made as a side project.

Another interesting aspect of the release of this Kid Icarus is its North American exclusivity. The game never saw a Japanese release. With 1990’s Balloon Kid also never released in Japan, 1992’s Wave Race doing the same again, and Metroid II releasing in North America months before hitting Japan, it seems Nintendo was somehow uninterested in its own home market. This is a bit of a mystery to me. The hardware sales do not support Nintendo losing interest in the Japanese Game Boy market: their numbers were strong. I’ve previously talked about a similar situation happening after 1998, where Nintendo released games in the US and Europe that were never released in Japan, but around 2000 the Game Boy Color hardware was selling four times faster outside Japan. This big discrepancy explains why their focus was on their growing markets between 1999 and 2001. In 1991, however, the Game Boy had similar hardware sales numbers around the world, so I don’t have an easy answer as to why Japan saw so few releases from Nintendo themselves for two years. Maybe I’m missing something?

An Angel on Your TV

Let’s talk about the original Famicom/NES Kid Icarus. I had yet to really play the original Kid Icarus before I decided to write this article. It’s a bit shocking to be honest, how hard they made the game starring the little angel with a naked butt in Valentine’s Day cards. Why is the game so hard? Kid Icarus’s controls are difficult to master, and all its mechanics are half-baked. Let’s discuss those sins.

The biggest one is the spawning enemies that populate the levels. Instead of each enemy being placed by the designer of the game, as in Super Mario Bros., the game simply assigns an enemy wave to discrete level segments. When the screen is scrolled within that segment, the game will always spawn the same enemy wave again and again until you scroll to the next segment. Then it will start to spawn the enemy waves that corresponds to that new segment. It makes the game more difficult because you’re always stuck facing enemies without getting a break, but more than that it’s just boring. There’s no intelligent enemy placement, it’s just wave after wave of the same enemies coming from the same directions, doing the same things over and over again. You don’t experience the artistry of a deviously placed Goomba thwarting your plans.

Another issue is hammers. Throughout the game, you’re slowly gathering them. They’re hard to find, since they’re acquired through a two-step process, and feel precious. What do you ultimately gain with this precious resource? They give you shitty one-shot mooks during boss fights. Boo-urns.

Another thing: Let’s say you manage to survive one of these really tough gauntlets, that are also criminally boring, and you are rewarded with an upgrade. However, the game requires you to have a minimum level of life for the treasure to unlock and be usable. Don’t get confused, it’s not like the Master sword in The Legend of Zelda that shoots only when at full health; you only need to hit the health threshold once to permanently unlock the upgrade. Why did they implement it that way? There’s no need for it, no reason. The Game Boy sequel unfortunately features the same boring gauntlets to receive the upgrades.

The Game Boy sequel unfortunately features the same boring gauntlets to receive the upgrades.

Oh and one last thing; any acquired upgrade is temporarily removed when you are in a dungeon. No increased arrow range, no defensive crystals, no nothing during the three longest game sections. Why? I think they realized the dungeons were too easy with the upgrades so they took them away. Whatever the reason for this decision, it’s just mean.

An Angel in Your Hands

There’s a lot less egregious stuff in Kid Icarus: Of Myth and Monsters. They fixed many things to make the game enjoyable.

- The controls are much improved, with jumps being much more adjustable. The game also introduces a slowed-down descent (with Kid Icarus flapping his small wings) when you mash the A button.

- You don’t die when you touch the bottom of the screen; the game simply scrolls in all four directions.

- Your upgrades work under the same system as in The Legend of Zelda; they work only when you are above a certain health level, making the game more fun since you have to thread carefully.

- Hammers are used to acquire all sorts of stuff, making them useful to collect.

- The game features a save function instead of a password system.

- The text encountered in each room is in coherent English.

- The game is much easier.

And best of all, enemies don’t haphazardly spawn without any artistry. Most enemies still spawn, but they spawn at a far slower pace, giving you more time to react and prepare for their attacks. They do so in a much more thoughtful manner, spawning in far smaller sections that feel much better arranged with the level layouts. This enhances the challenges you’re facing.

All these small improvements highlight the important thing about Kid Icarus: Of Myth and Monsters. It is a small-scale sequel without any big change to the original game’s formula. The game still has the same number of levels, the exact same structure, the same collectable upgrades, the same way to collect those upgrades. It’s commendable that they were able to adequately design the game to be brought forward to the Game Boy, but outside of this good work of translating the design of the game for a portable system while designing a sequel, the game has no inventive idea. It’s just a sequel. Let’s compare it once again to Metroid II, which decided to bring forward the premise and gameplay of the first game, but focused the whole game on the devious idea that Samus Aran was hunting down Metroids to eradicate the species. They implemented new concepts to go with their premise, with a counter to indicate how many are left to kill, the creatures transforming before your very eyes, and fun twists on the game’s formula during the game’s last act.

Conclusion

On Game Boy Essentials, I have tried again and again and again and again to stop people from considering a Game Boy version just a port of a game. The resolution, limited colours and portable nature of the Game Boy made it difficult to simply port a title to the console. The overwhelming majority of Game Boy games usually called ports are not, since they make fundamental changes to the original game. Kid Icarus: Of Myth and Monsters is no different, but boy oh boy does it make my job more difficult. An undiscerning person might quickly conclude that both games are but two sides of the same coin. Don’t make that mistake. Just play the game and see how an attentive developer with a good subcontractor can make a reasonably good game out of what was already an old-fashioned Famicom title by 1991.

Let’s give a final shootout to TOSE, the chameleon of game development; they’ll adapt to whatever is required, always staying invisible. In this case I don’t think they are at fault for the slight problems of Kid Icarus: Of Myth and Monsters. The people at Nintendo wanted two sprawling games for the Game Boy in 1991 that would particularly please the North American market. It’s just that this game was far less important than Metroid II: Return of Samus. TOSE simply provided what was asked of them. They once again played the role of the chameleon.

For my next article, I want to talk about Wave Race, Shigeru Miyamoto’s first foray into Game Boy development that happened the year after this game got released. That game started Miyamoto’s EAD division also releasing around one title a year for Game Boy. Damn eggplant wizards.

Damn eggplant wizards.

This article was first published on the .

This article was last modified on the .