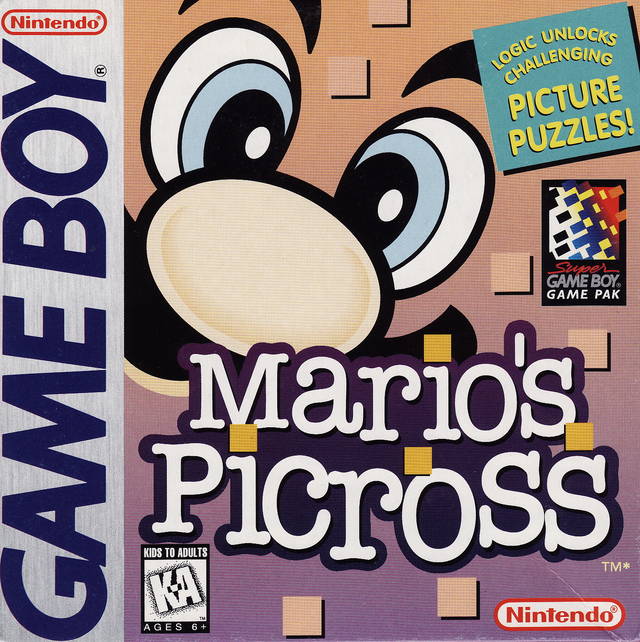

Mario’s Picross

- Japanese release in March 1995

- North American release in March 1995

- European release in July 1995

- Australian release in 1995

- Japanese release in March 2000

- Developed by Jupiter Corporation

Nono

I have a list of Game Boy games I want to check out and feature on Game Boy Essentials. With over 2000 titles released across the original Game Boy and Game Boy Color, I have looked at multiple sources to winnow the list into a reasonable amount of games to research further. I have yet to fire up every single game in an emulator, so I rely on a lot of common sense to figure out what is potentially essential. Initially, Mario’s Picross flew under the radar for most people, me included. I came upon it by chance, only knowing Mario’s Picross as an adaptation of nonograms by Nintendo. It was popular in Japan but nobody cared in North America, so Jupiter promptly stopped bringing their Picross games here. So knowing only this I decided to play the game for a minute and I fell in love. I went through the tutorial to learn the rules and liked it so much I immediately bought a book to try nonograms on paper. That’s how essential this game is; it will make you buy books!

A Primer on Nonograms

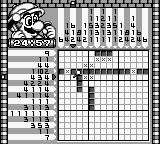

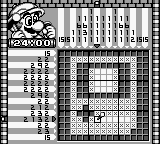

So what are nonograms anyway? A nonogram is a grid with numbers on its side indicating how many squares need to be pencilled in on each row and column. You apply logic to figure out which ones can be safely filled in and which ones can be safely discarded. When you’re done, you have a picture of an umbrella or a race car or something. To me nonograms are particularly soothing; you’re painting with logic instead of artistry, and I am way better at logic than artistry! It’s not that dissimilar to a Sudoku, but I’d argue it’s a more varied experience. It’s got more legs to get you to play just. One. More. Grid.

It’s-a-Me, Market Buster!

The question that fascinates me with nonograms is: why are they so utterly unpopular? Sudoku is everywhere, tends to be well-known, is the golden standard of book you buy at the cash register next to an Archie omnibus. Why aren’t nonograms, which are ostensibly the same thing as Sudoku (fidgeting around with numbers and squares) not more popular? I’ve thought about it and I think it comes down to two things. First of, Picross is one of those rare paper game that’s better on a computer.

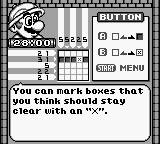

On paper, Picross is ostensibly about not making mistakes. If you make a mistake, it can easily propagate all over your nonogram like a virus and you’ve lost all your effort, since what you do has an impact on everything around it. So a one square mistake can propagate for dozens of squares before you realize you’ve messed up. So it’s a game about focus, about making sure your work is perfect at all times. When you screw up a nonogram on paper, you might as well throw the whole thing in the trash. It is stupidly difficult to figure out your mistake and walk it back. Mario’s Picross, on the other hand, will always tell you when you make a mistake, completely changing the focus of the game from perfection to quick execution. You see, if the developers only warned you of mistakes without any consequence the game would be meaningless, you could just bash at random until you had found all the black squares. But the developers at Jupiter put a timer on every puzzle. And when you make a mistake, you lose time. Only two minutes at first, but you lose four and then eight minutes per mistake. When you have thirty minutes to complete the puzzle that means you could quickly lose all your progress. Then you’re thrown back at the puzzle select screen and you can start the same puzzle over from scratch, with a leg-up because you remember what you already did, but now you have to do it all over again. So Mario’s Picross is a game about being as perfect as possible and properly managing your mistakes. I’d argue this is a more fun proposition than keeping perfect focus on paper.

Even though they are more fun as a video game, why are they absent from the books you buy at the grocery store? Beats me. I will obsess to an unreasonable degree about Game Boy games and their business prospects but I’m not going to start obsessing about the grocery store puzzle market. I’m not that much of a nerd.

The second reason I think nonograms are so unpopular is Nintendo will support something so well they steal all the oxygen from a genre. Since the Jupiter implementation of nonograms is more fun than doing it on paper, I don’t think anybody really saw the appeal beyond what Jupiter was offering. This would not be the first time they would do this to a genre. Look at the Mario Kart or Legend of Zelda franchises; two of the most popular game franchises ever. There are clones and adaptations to be sure, but never in enough quantity to really move the genre forward. Nintendo has the market cornered for vehicular mascot combat and action-adventure games strong on puzzles. They will bring you a version of those experiences every four years and capture a majority of sales. Why bother with imitations then? The same thing happened with monster-collecting, where Pokémon snuffed out all its competitors to extinction by just being so much more streamlined. I think ultimately the same thing happened with Mario’s Picross but on a much smaller scale: Jupiter did it well enough in a small enough market that nobody else bothered. Even though Nintendo quickly figured out the market wasn’t there for them in North America, no small developer gave nonograms a chance when they might have been able to turn a profit.

The Game Itself

There’s not much to say specifically about the game. It’s interesting to note that some puzzles are different from the Japanese version, which uses Japanese characters and objects (and also alcool) for its solutions. So Jupiter replaced some puzzles.

The controls are perfect for your intended purpose. I thought nonograms would have better controls on paper but they really don’t. Doing it on paper is time-consuming compared to the zippy dashes you can do on Game Boy. It’s a testament to how natural those controls are that when I tried the 3DS version I did not use the stylus but stuck to the D-Pad. It was just faster that way. The game nicely introduces the concept of nonograms to beginners.

The game nicely introduces the concept of nonograms to beginners.

One negative aspect is that the hard puzzles are accessible only after you complete all the easy puzzles. They’re so easy and brain-dead that it turns completing them into a chore and so I haven’t even bothered unlocking those harder puzzles. That’s a shame.

Competition From Strange Places

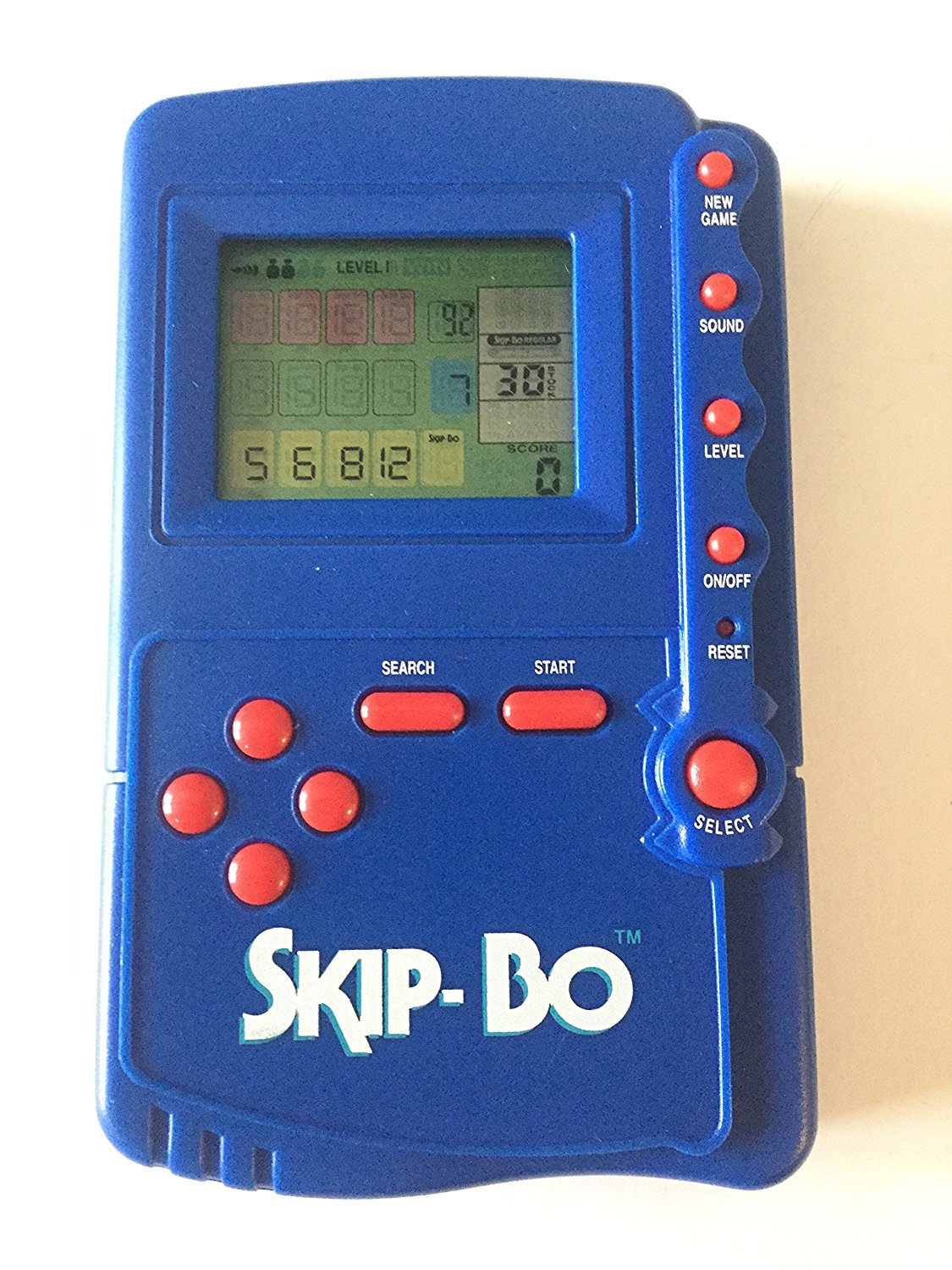

So Jupiter made a very nice version of Picross but it didn’t catch on in North America. Why? Mario’s Picross was not only competing against other Game Boy games when it was released; I remember that by the mid-90s electronic card games were ubiquitous and were competing against the Game Boy for the general population’s attention. My aunt had an electronic Skip-Bo and that thing was beloved at family parties. It was a smorgasbord of middle-aged ladies arguing about who would play next. They would play one game and then proudly declare they needed to buy one; the appeal for them was not that you could play the machine at a family gathering. The appeal was that you could play the thing alone at home. No need for those pesky in-laws to play with. They would never have thought to buy a video game on their own but once they were introduced to the little dedicated machine by peers who vouched for it, they could immediately see the benefit of such a machine.

When I instead brought my Game Boy that was a thing we kids would fawn over but adults would not give it a second look. It served no purpose, replaced no family members for them. I guess my adult family members were not enthralled by The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening like my nephews were. But that little Skip-Bo machine was the shit to them. Even though it had an unlit screen, like the Game Boy. Even though it needed more batteries than felt reasonable. Even if it could only play one game, goddamn Skip-Bo of all things. It was ultimately cheap with a veneer of adult respectability, since it was sold in the toy section but next to the playing cards. They are great examples of what adults thought a portable game was in the mid-90s. My aunts are still playing games today, going on Facebook for social games and buying iPads for Candy Crush. You didn’t even need the manual; the back had all the instructions you needed.

You didn’t even need the manual; the back had all the instructions you needed.

In 1989 Nintendo could bring out a new puzzle concept with Tetris and seduce the whole planet. By the release of Mario’s Picross in 1995, dedicated electronic puzzles had muddied Nintendo’s lock on the mindshare for portable puzzles. In a sense it was the revenge of the LCD games I talked about in my Super Mario Land article. While there wasn’t much left to do artistically with LCD screens in terms of games for kids, you could still make an interesting product for adults. All of that to say that adults were no longer a solid market for the Game Boy in 1995. I don’t want you to get the wrong idea: I don’t think adults completely stopped playing Game Boy. I just think the initial awe over the machine’s uniqueness had subsided. The Game Boy in 1989 was the next Japanese wunderkind after the Sony Walkman. Everybody wanted one. By 1995, it was still the best portable system by begrudging acceptance that nothing better had surfaced. You would constantly hear on TV, from friends, from everybody that this portable system was finally going to displace the old crusty Game Boy. I remember watching a kids show about technology that spent thirty minutes showing off the Sega Nomad and trying to convince you that this was finally going to be the system to kill the Game Boy. It took Nintendo until 1998 to finally kill their baby themselves with the Game Boy Color and it was merely an improved iteration.

2017: The Future

Nintendo ultimately gave Picross another go in North America with the DS, to more success since the DS had a lot of appeal with a more varied audience. On DS and 3DS, they released great versions of Picross, but they also pushed the genre forward with versions where you interact with a 3D puzzle. Those felt ho-hum. They made Pokémon Picross more recently, a free-to-pay title for 3DS even though Picross does not gel with micro transactions at all. It’s an attempt at emulating the crass games on iPhone and Jupiter did not push that further: their next game, Picross S for Switch, is a conservative paid release.

Conclusion

Mario’s Picross shows that Nintendo never stopped trying to chase the next big puzzle game. The next Tetris, so to speak. Throughout the ’90s they released many puzzle games, and they’ve all but stopped searching nowadays because they figured out that their adult audience that bought Tetris to play puzzle games had moved on to cheaper, dedicated, game machines and we now play puzzle games on our phones. The people at Nintendo eventually got their next big mainstream breakthrough. Just not with a puzzle game, but with Pokémon.

This article was first published on the .

This article was last modified on the .