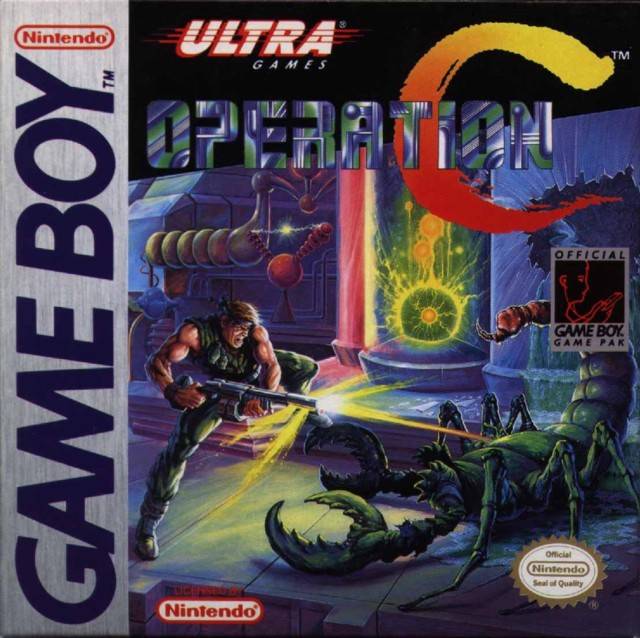

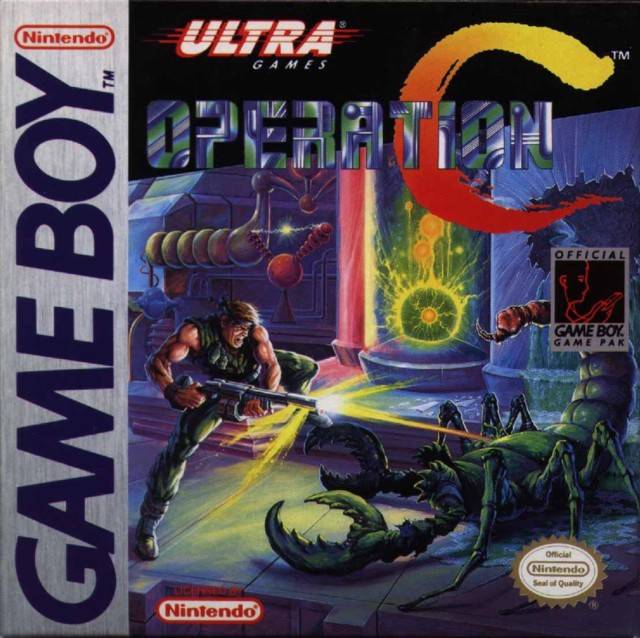

Operation C

- Japanese release in January 1991

- North American release in February 1991

- European release in May 1992

- Developed by Konami

Baby Contra

Making a competent adaptation for Game Boy is not an exact science. In my previous article, I argued that Biox’s Mega Man II has the basic concepts done properly, but that they just mangled the execution. The skeleton is OK but the rest of the body is too weird.

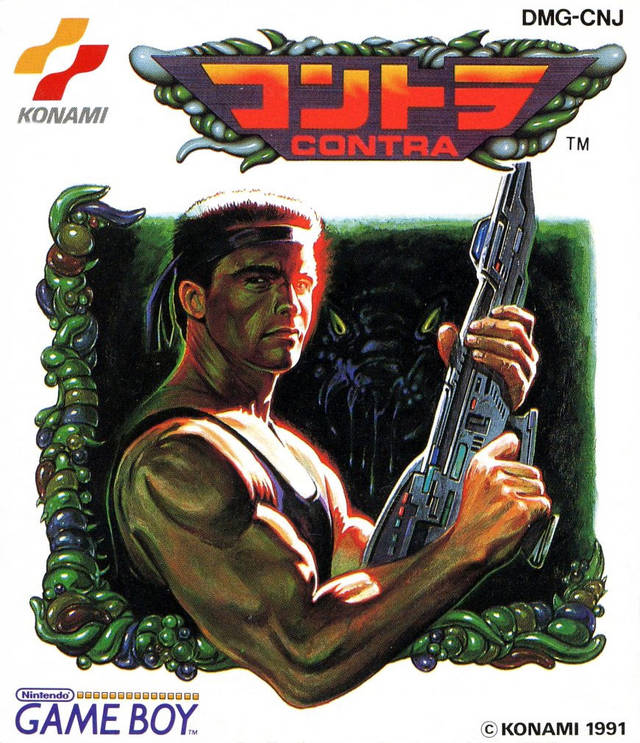

On the other hand, Konami’s Operation C, known in Japan as simply Contra and in Europe as Probotector, is the real deal. The sprite size, walking and jumping speed, level of detail, everything is well tuned, so the skeleton of the game is great. Then they went ahead and added all the trimmings. Levels, weapon selection, game length, enemy types, difficulty. All those details fit perfectly too. Konami really got it right, just like with their previous game I covered, Nemesis. Once again, the fine people at Konami made an essential game. I still remember to this day the joy of playing this game when I was a kid. And I played this game late, since a friend first lent it to me around 1998.

Collect S to Win

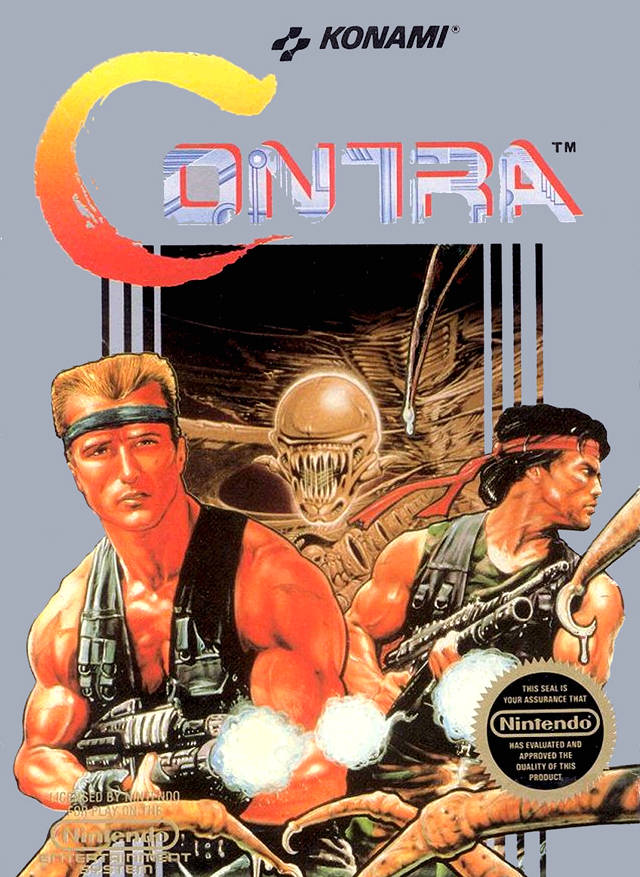

Close your eyes and think of the Contra games. What images come to mind? For me, it’s mostly Contra III: The Alien Wars on SNES and its hyperactive attitude. I think of explosions, frenetic jumping from missile to missile while flying through the air, and more explosions. That’s the later Contra series’ attitude, having evolved its own style based on explosions and insane situations. But Operation C came out earlier, when the games were action-packed to be sure but they were a bit more sedate. Their marketing and situations were clearly trying to bank on the love of Predator, Alien and Rambo with a good measure of Commando thrown in. I’m being nice here, they weren’t just going for the style of those movies, they were literally tracing promotional pictures for those movies to put on the game covers. It’s Rambo and Matrix fighting against the Xenomorph! No wonder everybody loved Contra.

It’s Rambo and Matrix fighting against the Xenomorph! No wonder everybody loved Contra.

Within those traced packages where games that were a bit more . . . subdued than what would suddenly burst through with 1992’s Contra III. What we have with Operation C is the last hurrah of that classic Contra era. The Japanese cover has a blatant mix of Michael Biehn and Arnold on its cover but the American game’s box is clearly not trying to sell us on a Stallone/Schwarzenegger video game, it’s forging a new unique identity for Contra (fun fact: the artist for this cover, Tom DuBois, is now a hardcore Christian artist). The game itself is a Game Boy adaptation of the NES adaptation of the arcade Super Contra. These three-step adaptations are way more common in video games than you might think and here we have one of my favourite ones. This little game is just awesome.

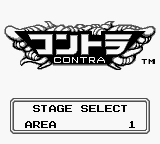

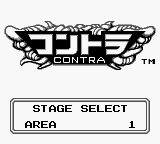

I often hear commentators, youtubers, podcasters start talking about a Game Boy game with: Even though it’s on Game Boy, it’s still good. How surprising! These are benign comments not given much thought, a reflex to think that portable systems are somehow a lesser thing, that somehow the natural state of a portable game is to be bad. But there is no surprise that Operation C is an extraordinary game. It was made by a company with a stellar reputation for quality in 1991, a small group of four internal developers used to the Game Boy. Of course it’s good even though it’s on Game Boy! The Japanese version allows you to select any of the first four levels.

The Japanese version allows you to select any of the first four levels.

Remember, Sully, When I Promised to Kill You Last?

Let’s talk about the story. Actually let’s not because I don’t care! When I go on websites online to read about Contra games there’s always this undue attention paid to the story and the timeline and how the American games are not set in the same period as the Japanese ones. It’s all useless hogwash! Nobody has ever played a Contra game to continue exploring the rich story of the Contra universe. You just want to walk right and kill stuff from 80s movies! The ad copy is clear that it only has single-player. It was important to warn people it did not have Contra’s greatest feature: simultaneous coop.

The ad copy is clear that it only has single-player. It was important to warn people it did not have Contra’s greatest feature: simultaneous coop.

I Lied.

The game is one Megabit (not byte), so it’s a very small program. This does not mean anything without context, so let’s bring it to something you will understand. Operation C is twice as big as Super Mario Land in size. That’s not big! Super Mario Land is minuscule, with its small levels and very limited tileset. So Operation C has more room in the cartridge for enemy types, for longer levels and more detailed tiles, but twice the size is not a panacea. We’re still talking about 131 kilobytes (not bits), a laughably small amount of space for a complete program with music and graphics. A small programmable space like that means the programmers and designers could not do everything they wanted. They could not draw and program too many enemies, meaning they had to reuse enemy types and their projectiles. They could not draw too many tiles, meaning the levels could not be too detailed. They had to get wise with the tiles they could fit on the cart to make interesting environments. Those are big limits to what you can do.

As the Contra series got older, you had more and more unique situations that you faced that correlated directly with an increase in cartridge size. With Contra: Hard Corps on Genesis, the series reached the apex of this evolution with a constant boss rush, with barely any reused enemy or environment to be seen. Contra went from an intelligent repetition of enemies and patterns to a series of custom-built set pieces.

And Operation C is the most repetitive of the Contra games. The fourth level, one of the game’s two overhead level, has only two enemy types and one environmental hazard. Yet it manages to stay frantic and surprising. Even the boss reuses the same projectile as one of the enemy types in the level but its new projectile patterns make it fresh. They really stretched every little concept they built. It’s really surprising to see how much of the game is recycled while staying surprising and vibrant. They pull every trick in the book to make you forget the recycling.

Again in level four, you have those weird invincible protrusions that come out of walls to try and hit you. They use every permutation of pattern I can think of to give you a different challenge every time you encounter them, and they place enemies in varying places to make it more complicated to navigate around them. I urge you to play the game and look for the tricks the developers used to maximize their assets. It’s fun!

The Size of Scene Elements

The developers have applied the same lesson here as in Nemesis. Everything in the game is a bit smaller than on NES, but not too small. You still don’t see as high or as far. They’ve made your character literally a head smaller. Literally a head smaller.

Literally a head smaller.

So your character is smaller but he’s not small enough to take the same amount of space as on a TV; he’s still so big that he eats up more space. That’s fine, as we’ve seen with Nemesis and The Bugs Bunny Crazy Castle. You adapt the gameplay to fit the screen resolution, and that’s what they did here. They were helped in this by how the series works. You see, the Contra dude (I steadfastly refuse to remember his name) is slower to move than Mega Man or most other characters in platform games. He’s not zipping around as fast and jumping as much. You move slower, have fewer jumps to clear and spend much more time aiming at enemies coming from all directions. Those concepts were much more suited to the smaller resolution of the Game Boy. You don’t need to redesign everything around your main character to make the game work; you just have to be looser with enemy aggressiveness and placement. They also limited the amount of flying enemies you see and kept the two overhead levels on a tight leash in terms of bullet hell. That makes Operation C easier than the console or arcade versions because you can’t have enemies pop out on the screen at the same rate as on those; the screen is smaller and you’d be swamped. So enemies telegraph their moves a bit more, move a bit slower, shoot a bit less bullets. No enemies in Operation C are as fast as the dogs in the first level of Contra III.

Small Quality-of-Life Improvements

The game introduces auto-fire to the series, meaning you can hold the A button to keep firing. That way you don’t have to mash the A button all the damn time. It’s a different approach that changes the game a lot, reducing the amount of time you spend aiming and it turns you into a firehose of bullets. You need to be challenged in different, less interesting ways because of that. It was a necessary change in hindsight to keep the series approachable and save our thumbs.

All subsequent games would use the same system, with Contra 4 having the genius idea of allowing both shooting methods. In Contra 4, made by the fine folks of WayForward Technologies, holding the button gives you a satisfying, steady stream of bullets but mashing the button makes even more bullets appear, giving you that small edge you so often need. So you can rest your thumb on the button most of the time and mash when you get in a tight spot. It’s so intelligent as to be maddening. Why did nobody else thought about it before? Oh WayForward, how I like thee!

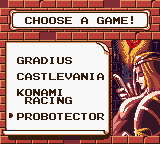

Don’t worry, I haven’t forgotten to talk about the Konami code too. On the North American (Operation C) and European (Probotector) releases, punching in the code allows you to access the level select from the original Japanese version. The Japanese (Contra) version instead uses it to give you nine lives. Look up the GameFAQs description of what each code does for more details.

Let Off Some Steam, Bennett.

We need to talk about censorship, kids. First off, it’s not what you think. If a country has a legally binding review board that deems cultural content inappropriate for minors and thus enforces that the material only be sold to adults, that’s not exactly censorship. Nobody’s harshly censored, you’re just deemed inappropriate for sale to children. An adult will have to make the call on whether or not their children can play those games.

So if a company then looks at its video game, thinks there might be a chance its clear pastiche of all the movies glorifying war in the ’80s might be deemed inappropriate for children and then voluntarily modifies its game to make sure its product can be sold directly to children, that’s again not exactly censorship. So why am I talking about this? Because Contra has a complicated history with European classification boards, that’s why. When the time came to bring the original Contra arcade game to Europe, I guess the political heat on the Iran-Contra affair meant the name was deemed inappropriate: the arcade game was called Gryzor in Europe. The sequel Super Contra did not change its title in Europe, probably because by 1988 the whole political catastrophe was no longer in the news. Still, the series, ostensibly about shooting aliens and robots in the face, has forever been attached with the illegal smuggling of cash from secret Iranian arms deals to fund a brutal antigovernment rebel group in Nicaragua by the United States. And Konami did not innocently fall into this controversy. Contra and Super Contra start with jungle levels, which, of course, forces you to connect the game with the Contras themselves, and the original arcade title has a music track called Sandinista, after the socialist government the Contras were fighting against! So the people at Konami knew what they were doing. Even in North America they somewhat retired the Contra name for a while, using Super C and Operation C to obfuscate the connection.

Now that’s just the entrée in the long history of Contra and controversy; with the console version of Contra in Europe, the German Protection of Young Persons Act reared its head. It’s a law meant to protect children and teenagers from being exposed to material deemed inappropriate for them. While most countries are content with having industry-regulated classification boards giving ratings to games, the German went one step ahead and made it a government-controlled board. Couple that with the fact that it is very clear that media carrying content glorifying war is not to be sold to minors, and you have a skittish Konami. Let’s be honest here: Contra is totally glorifying war. So Konami did the sensible corporate thing; they completely reskinned Contra with robots instead of humans and changed the name for good measure to Probotector. They then released this version for all of Europe. They self-censored.

They did this of their own volition, since they seemed to have never submitted Contra in its original form for any classification in Europe. They only submitted the modified robot version. So every subsequent game, including Operation C, replaced all the humans with robots. I kind of like it, the robots look rad. It’s a nice change of pace. I don’t think Europeans missed out on anything by having robot-on-robot action.

Standard Collection Reissue

Just like Nemesis and most of the early Konami Game Boy titles, it was rereleased with the four-volume Konami GB Collection in 1997 in Japan and in 2000 in the UK. The same comments I gave to Nemesis apply for Operation C. The colour palette of the UK GBC version is woefully inappropriate, really giving credence to all the negative comments you get about the Game Boy Color’s pastel colours. You can often see the jagged edges where the tiles change colour palettes; it’s not a good job. What is interesting is that the European release keeps the unique title for the European market, Probotector, but skips the replacement of the characters with robots. With the arrival of the current German classification board in 1994, what is and isn’t fair to release to minors in Germany had obviously changed. Oh and the Konami GB Collection was never released in Germany anyway, just in the UK. All of this makes it the last game to use the Probotector title (on consoles, Konami had stopped renaming their European versions after Contra: Hard Corps on Genesis in 1994). They clearly just took the easy way out: the game still uses the Japanese version, since it features the level select absent from the North American and European original releases.

Conclusion

Operation C is an essential step in the Game Boy story of Konami. It again shows that Nemesis was not a fluke. The fine people at Konami seem to have understood the Game Boy right away. I have not talked so far about all of Konami’s output on Game Boy in the early days, with games like Motocross Maniacs, Twin Bee, the first TMNT game and particularly Castlevania: The Adventure showing other attempts by Konami that were not always successful. I’ll get to those in due time but I can say with confidence that Konami had a very good at-bat on Game Boy.

Compared with their compadres at Capcom who stumbled twice with their mascot Mega Man and the subcontractors they entrusted him with, Konami was on point from the get go on Game Boy by doing the job themselves.

This article was first published on the .

This article was last modified on the .