Pokémon: Red Version, Green Version, and Blue Version

- Japanese release in February 1996

- North American release in September 1998

- Australian release in October 1998

- Brazilian release in 1998

- included w/ Game Boy Pocket

- European release in October 1999

- North American release in 1999

- Australian release in February 2016

- Nintendo 2DS Special Edition Bundle

- Developed by Game Freak

A Game Boy Resurrection

Before it became a perennial staple of popular culture with its card games and anime series and yearly releases, Pokémon was a world filled with mysteries. Friends would trade Pokémon monsters using the Link Cable but they would also trade legends, tall tales of dubious veracity, secret incantations of duplications, and methods to find strange and forbidden monsters.

That’s why, dear reader, I invite you to follow me starting on Route 1 throughout Kanto as I unveil the answer to the following mysteries:

- What Secret Game Probably Inspired Pokémon’s Creator?

- What Did Game Freak Publish Before Making Video Games?

- Which Surprising Pokémon Was Born First?

- What Horrible NES Game Funded the Development of Pokémon?

- Who Really Owns the Pokémon Franchise?

- Why Does the Game Have a Green Version in Japan?

- Why Did It Take Two Years for the Game to Be Localized and Released in North America?

- How Did Pokémon Teach Me About the Idiosyncratic Québec Media Landscape?

- Are There More Than 150 Pokémon?

- Is the Game Any Good?

Well, maybe that mystery about the amount of Pokémon is a bit dated, considering there are now [he looks at Bulbapedia] 901 Pokémon, and that’s without counting all those variants and gigantic versions of all the old ones. I even heard there are some Pokémon amongst the newer ones that aren’t well designed! Gasp!

Let’s forget all about those newer creations and go back to a time when everybody was wondering if there would ever be another game and Pikablu had not yet captured our imaginations.

What Secret Game Probably Inspired Pokémon’s Creator?

First let’s go back to 1989 to reveal the answer to our first mystery. Tajiri Satoshi, Pokémon’s creator, had a very fruitful first encounter with the Game Boy. While people were immediately drawn to the screen of the portable device Tajiri was inspired by a humbler element of the console; its Link Cable. He imagined little insects travelling along the wire, going from one Game Boy to the other. From this simple idea Pokémon was born. At least that’s the myth, told time and time again by Satoshi to explain the genesis of his concept.

I’m a bit skeptical of this perfect story absent of any influence from other video games. He knew video games well and I refuse to believe Satoshi wasn’t influenced by Makai Toushi SaGa. Known in the West as The Final Fantasy Legend, it’s the first role-playing game for the system coming in a mere six months after the system’s initial release. It showed that the Game Boy was a perfect system for RPGs. I covered it previously, and I marvelled at how it attempted so much, so early in the system’s life. The game features monsters in your party, that can evolve (and devolve) based on eating the meat of your defeated enemies. I’m inclined to believe that Satoshi played Makai Toushi SaGa and got some inspiration from the game. Perhaps he even dreamed not of insects travelling along the wire but of the monsters in Makai Toushi SaGa.

I don’t want to diminish the accomplishments, especially since the monster trading is a novel idea worth all the praise it has gotten, but there is this tendency with developers, and Japanese developers in particular to shy away from mentioning inspirations from other video games. All we can do is presume which is what I’m doing here.

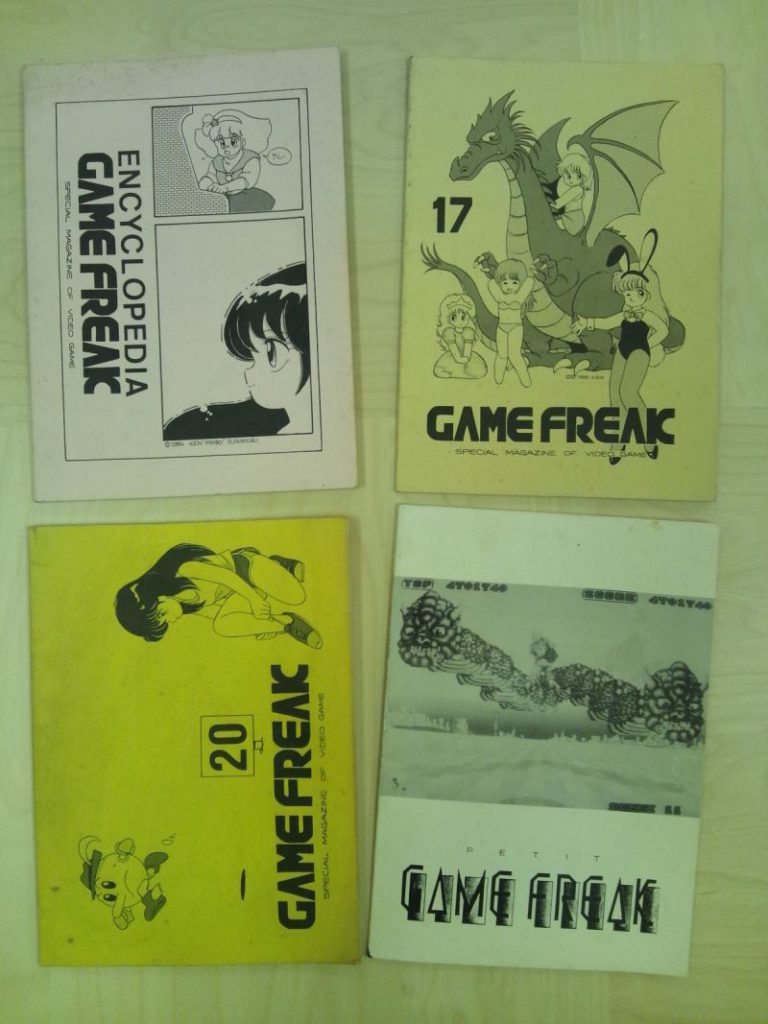

What Did Game Freak Publish Before Making Video Games?

Satoshi was a publisher of a fanzine focusing on arcade titles which he worked on alongside Ken Sugimori, the artist drawing the fanzine’s art. Ken would later become the main artist for the game.

I saw some original copies of their fanzine in a museum exhibit and they were underwhelming. There’s no magical quality to them; they were low quality Japanese fanzines made with a lot of love but still simply fanzines. Those little staples books are relevant because they birthed Game Freak and put Satoshi and Ken together allowing them to later pivot to video game development.

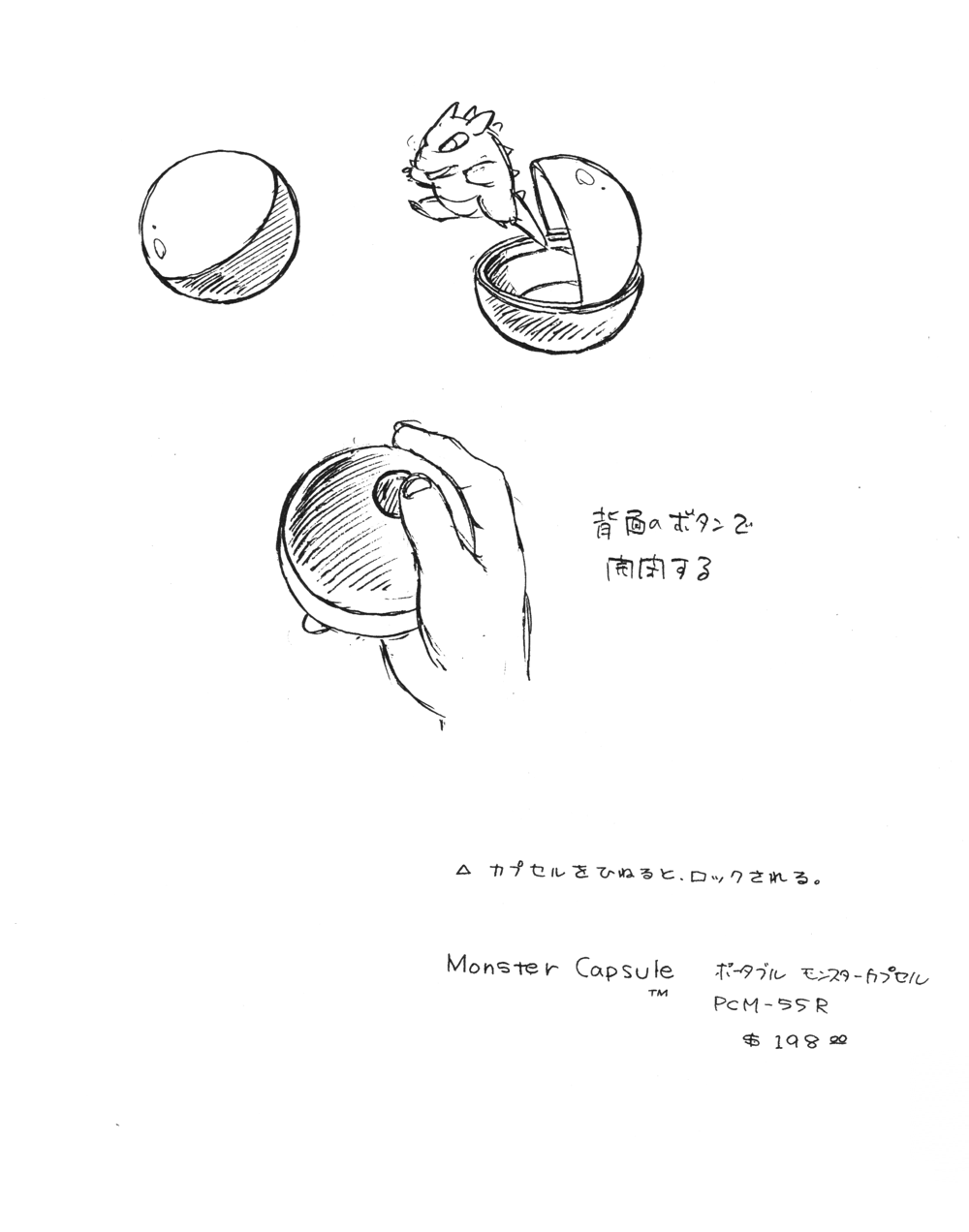

Which Surprising Pokémon Was Born First?

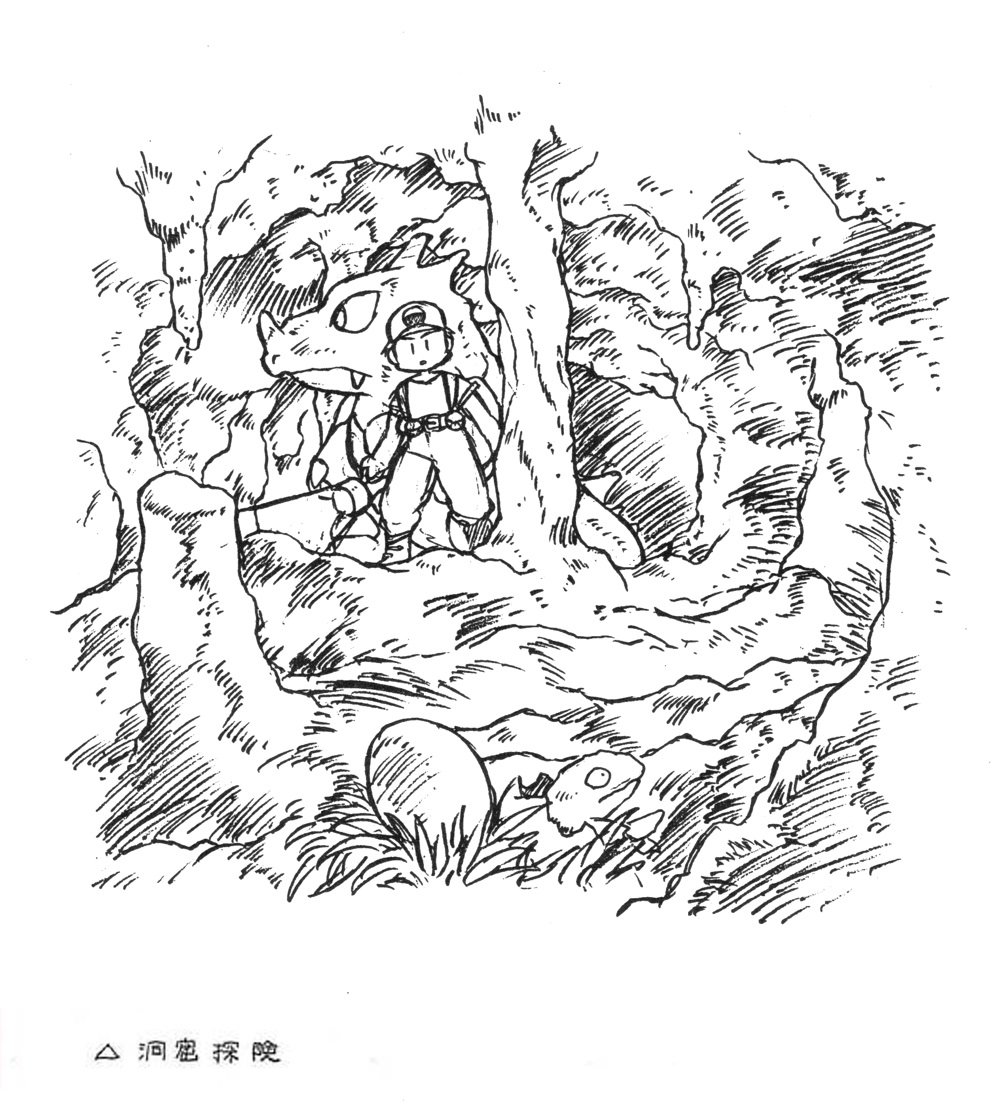

The original concept for Capsule Monsters, which would become Pocket Monsters before release, used generic creatures that looked like dragons and dinosaurs. Amongst those dinosaur-looking creatures, one has been identified as the first Pokémon, the first creature that was imagined during this early concept and survived all the way to the release of the game. Hey look who’s in the back of this very early sketch.

Hey look who’s in the back of this very early sketch.

Rhydon was the oldest design to end up in the final game. He is a very generic-looking dinosaur with a rhinoceros horn, so it makes a ton of sense that he is the oldest Pokémon, coming from the era where all the creatures were inspired by dinosaurs. More creative concepts like Electabuzz would come later.

What Horrible NES Game Funded the Development of Pokémon?

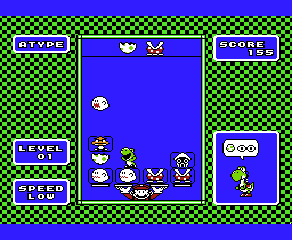

Once again I have to make a personal connection before I answer the question because I’m a narcissist. When the Super Nintendo came out, I didn’t have one. I had gotten a second-hand NES earlier in the year so of course my mother was not about to start upgrading her six-year-old son with the latest and greatest. Since I was smitten with Yoshi and dreamed of nothing but riding him in Super Mario World, I asked my mom to buy me Yoshi for NES as a birthday gift. When I started playing this is what I saw. What a giant piece of shit.

What a giant piece of shit.

It’s a shitty puzzle game. To rub even more salt in the wound, there’s a better Yoshi puzzle game, Yoshi’s Cookie, and Yoshi is not even half as good as Yoshi’s Cookie. It’s just terribly uninspired and boring.

So what’s the Pokémon connection? Game Freak was cash poor during the early ’90s, and Nintendo bailed them out because they believed in their Pocket Monsters concept. I think part of the help they got from Nintendo was to be assigned to develop Yoshi. This allowed them to make enough money on a surefire hit based on a hot new character,

and to learn the complicated details of video game development. They could keep going and maintain the development of Pokémon using the money they made from Yoshi.

Now I can sleep at night knowing that I directly financed the development of Pokémon all the way back in 1992. Well, I guess my mom financed the development of Pokémon. Be sure to thank my mom if you see her.

Who Really Owns the Pokémon Franchise?

When Pokémon Go was initially released on iOS and became the global phenomenon of the summer of 2016, Nintendo’s stock in the Tokyo stock Exchange suddenly doubled. Nintendo, unfortunately, could not enjoy this sudden excitement for their stock. Because they knew that investors would cool when they learned that Nintendo is not the master of the Pokémon franchise. They clarified their complicated relationship with Pokémon Go, and the stock went back down. It’s obvious they were scared the stock would fall harder once the game was monetized and Nintendo would make no money from the game. You see, Nintendo didn’t make Pokémon Go, and they don’t even wholly own the Pokémon franchise. In fact, they do not receive direct revenue from Pokémon. What? Nintendo doesn’t outright own Pokémon? Then who does? Three companies do, with a fourth special case, and let’s go through each one.

Game Freak

The OG gang, the company created by Tajiri Satoshi, Masuda Jun’ichi, and Sugimori Ken to publish their fanzine that later transitioned to video game development. It is at this company that Tajiri created the whole Pokémon concept and it is still to this day the birthplace of any new concept or monster. No other developer or licensee can willy-nilly create a new Pokémon called Pikatwo; Game Freak is the sole place where new Pokémon are birthed. They have stayed a small developer, even though they’re the idea factory of the largest media franchise in the world. The small size is seemingly to foster creativity and maintain a high level of control. Whenever anybody complains that the graphics in a Pokémon game are terrible, their minuscule size is the reason. They simply do not have the manpower to rival the bigger studios inside Nintendo.

Like I just mentioned, they’re the company responsible for the development of Pokémon games but only what is usually called the core games; think Pokémon Sun or Pokémon Legends: Arceus. Altough that distinction is getting muddled, with the latest remakes, Brilliant Diamond and Shining Pearl being developed by ILCA, a relatively obscure Japanese developer. Quick aside, they obviously delegated those two remakes to ILCA to work as much as possible on Pokémon Legends: Arceus, a top to bottom reinvention of the game concept. With once again terrible graphics.

Nintendo

Between the birth of the idea from the mind of Tajiri Satoshi and the release of the first game in 1996, Game Freak presented the project to Nintendo and the company became its publisher. Nintendo also acquired a stake in the franchise itself. This is particular since a publisher does not necessarily own the intellectual property of the game it publishes: you can look at Banjo-Kazooie for example, initially published by Nintendo in the ’90s but now available on Microsoft consoles. This could happen because the company that made the game, Rare, did not sell the ownership of the copyright to Nintendo even though Nintendo owned a controlling stake in Rare; they instead collaborated on the development and distribution. If I had to hazard a guess as to why Nintendo bought a stake in the Pokémon franchise itself I’d say it’s because Game Freak needed the money to finish the game.

In direct terms, Nintendo shares the Pokémon copyright with the other three companies holding it. It shares the trademark in Japan with those three companies and is the sole owner of the trademark in the rest of the world. Don’t forget to look up the difference between a copyright and a trademark kids. This share of the franchise means Nintendo considers Pokémon its own: Pikachu and the rest were in Super Smash Bros. from the first game’s release.

To most people everything related to Pokémon is made by Nintendo when the truth is far more complicated. Nintendo’s not even the sole publisher of the Pokémon games on Nintendo’s own consoles. They share that role with the Pokémon Company that they also happen to co-own with the other companies with which it shares the Pokémon copyright. I told you it was complicated.

Creatures Inc.

Who is Creatures Inc. exactly? It makes sense that Game Freak and Nintendo share the franchise, but why is there a third company in the mix? According to Masuda Junichi, a co-founder of Game Freak and the current creative overseer for the games, they were the producers of the first game. This is strange since the producer of a game is usually a person working for the company making the game, not an outside company. Thinking about the situation, I don’t think they’ll ever admit it, but I think Creatures Inc. was brought in to help Tajiri finish the game. He couldn’t do it alone since he had never produced a game before: he was a fanzine writer.

The history of Creatures Inc. also seems to confirm my thinking. Creatures Inc. is made-up of former employees of Ape Inc. who had already supported a visionary artist with no video game experience to produce a very personal RPG based on a fairy-tale version of our modern world. I’m of course not talking of Pokémon but of Itoi Shigesato and his game Mother for Famicom, which we know in the West as Earthbound Beginnings. It turns out the employees of Creatures Inc. had already helped with the same type of production job!

Since they helped finish the first Pokémon game their contract clearly gave them partial ownership of the franchise, and they went on to create the Pokémon trading card game (it wasn’t made by Wizards of the Coast who simply localized it) and other elements of the franchise. Once again if I had to guess as to why Creatures own a part of the franchise it’s because Game Freak couldn’t pay them to help them, so they paid them with a franchise stake.

The Pokémon Company

Created by all three above companies to initially manage the Pokémon Center stores popping up in Japan in the early ’90s, it quickly became the company managing the licensing of Pokémon. So if a toiletry company wants to put Pikachu on a towel, they call The Pokémon Company, not Nintendo. The question arises, though: why not let Nintendo manage the licensing?

These days, Nintendo is good at licensing its characters for interesting products. I’m particularly impressed by the Mario Lego sets, with its special Mario Lego character with screens for eyes, a small speaker and an NFC reader allowing him to emote and react to specially tagged bricks. Or Mario Kart Live, the toy that allows you to kart race in your own home. In the mid ’90s, however, Nintendo was only able to give adequate focus to the Japanese market. Licensed Nintendo products overseas like toys, cereals, books, or content like TV shows and movies were all terrible. In a recent reunion organized by the VGHF, Gail Tilden, first editor-in-chief of Nintendo Power Magazine mentioned that licensing at Nintendo throughout the ’90s was barebones and that the magazine had to produce its own marketing material.

So I don’t believe Nintendo was prepared to deal with Pokémon: they never managed to license anything worthwhile related to The Legend of Zelda, for example. They were a toy maker, not a licensing manager. So a fourth company was emboldened to manage everything related to licensed Pokémon products.

The Pokémon Company now even co-publishes the games on Nintendo consoles and has become the sort of brand manager for Pokémon in its entirety, managing tournaments, products, and announcements related to the franchise. So they have never stopped growing their importance as time went on. If one company is responsible for the successes and mistakes made with the franchise now, it’s them.

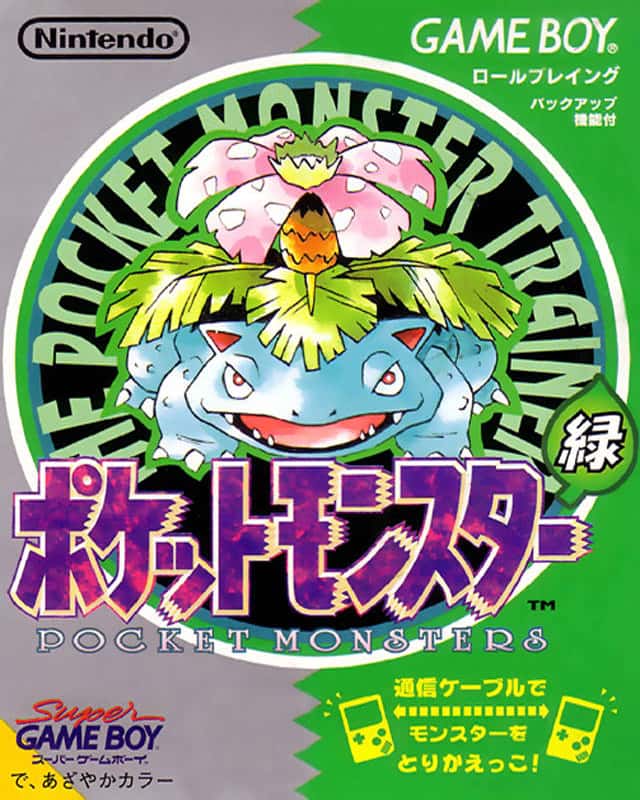

Why Does the Game Have a Green Version in Japan?

Upon its initial release in Japan the two versions of the game were the red and green versions. Most people are aware of this regional difference in versions since the remakes on Game Boy Advance feature those original colours but I still feel compelled to explain it.

One fascinating invention of Pokémon is the concept of the dual versions. To foster the trading of monsters between players, the game came in two flavours, green and red, with a specific subset of Pokémon unique to each game. This meant that to complete your Pokédex (that you owned one copy of every creature) you have to trade with someone else. Someone with a different version. There isn’t an overwhelming list of Pokémon unique to each version, just a handful, but it taught everyone that Pokémon is about trading with other players.

As the Japanese in early 1996 were going crazy over those two initial versions, Pocket Monsters: Red and Pocket Monsters: Green, players also discovered the game had some rough edges. The graphics were clunky, the monsters didn’t look exactly the same as in the manual illustrations, and the game had some unfortunate bugs. A version that featured updated graphics and fixed some of the bugs was released later in 1996. This was called Pocket Monsters: Blue. All the later localization work was based on this improved game so no one outside Japan ever saw the original graphics. They kept the original monster distribution from Japanese Red for international Red, and transposed the Green distribution into the international Blue version. At this point, why not go all the way and localize Green instead? I guess Blastoise has cannons, that’s too cool to pass up.

We’ll talk about Yellow in its own article.

Why Did It Take Two Years for the Game to Be Localized and Released in North America?

This one is easy to answer: Dragon Quest. Back in the days of the Famicom, Dragon Quest seduced the Japanese with its quirky reinvention of the role-playing game. By Dragon Quest III, the series was a societal phenomenon. Enix famously moved releases to Saturdays, to alleviate public concerns from some Diet legislators.

Pocket Monsters was obviously going in the same direction in Japan. Everybody and their mother knew about the game and anything related to the franchise was a guaranteed smash hit. But there was one major flaw with Dragon Quest: no one cared about it outside of Japan. It had its fans but Nintendo was directly stung by its poor North American reception. They published the localization in North America and had such a sale dud that they had to give the cartridges with Nintendo Power subscriptions to get rid of their unsold copies.

This failure led to years of statements by employees of Nintendo that non-Japanese players didn’t like RPGs. They weren’t wrong; RPGs sold far less in North America than in Japan, but it was a chicken or the egg situation. RPGs had a ton of text to localize, which meant a protracted localization process, and used far more memory, which all meant a more expensive product. For these reasons few Japanese RPGs were localized and brought West meaning it was much harder to build an audience for the few games that did see a release. When Nintendo tried their hands at bringing RPGs to North America they always had disappointing results. Earthbound left a particularly sour taste to everyone involved at Nintendo of America according to Pokémon translator Nob Ogasawara. It was very difficult to translate with Mother creator Itoi Shigesato getting directly involved and sold very poorly, killing any hope to reverse the trend of underperforming RPGs with Earthbound.

This illustrates how careful everyone at Nintendo was regarding Pocket Monsters. It was yet another reinvention of the role-playing game and the same lack of interest for the genre could hurt them once again, just like Dragon Quest and Mother/Earthbound.

They had to try releasing it outside Japan, it would be ridiculous not to, but they wanted to take their time to get it right. They considered redesigning the creatures to increase their western appeal but ultimately abandoned the idea. Time was ticking and on top of that the industry had started to change since the release of Dragon Warrior. We were now under the auspices of an entertainment model. In effect, the marketing challenge for game publishers had shifted. Before, you had to get a consumer to buy your game. Now, you had to get a retailer to stock your game in the first place.

Starting around 1994, the software industry transitioned to what Nina Schulyer called the entertainment model of marketing. If retail shelf space was harder to come by and lasted for a shorter time, the idea was to put more resources into generating hype in advance, raising awareness for the title before it was even released, the same way Hollywood studios promoted movies. […] It’s no coincidence that right around this time also marked the beginning of Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3), a massive game industry marketing event that was originally intended as a way to advertise directly to retailers.

Excerpt of The incredible boxes of Hock Wah Yeo from The Obscuritory.

Nintendo could not put a game on the shelves and spend months hyping it like they did in 1989 with Dragon Warrior; retailers did not have the patience for that. Considering the original Pocket Monsters in Japan became a phenomenon through word of mouth and needed months to reach its sale potential, it benefitted greatly from the old model where the game sat on shelves waiting for consumers.

So Nintendo, Game Freak and Creatures wisely prepared something special for the release of Pokémon. Nintendo internally translated most of the core concepts of the game and would then use those translated Pokémon names and concepts for the anime localization. Those two products, game and anime, would both release together in the fall of 1998. A one-two punch of Pokémon content, which would hopefully entice american children. For good measure, the surprisingly successful Trading Card Game would follow the next spring, distributed by Wizards of the Coast, the people behind Magic: The Gathering.

It took them a while to arrive at this plan, and required a lot of effort to implement. History vindicated their patience.

I was 10 in 1996 when Pocket Monsters was released in Japan. I was still playing with my Game Boy even though it felt like the rest of the world had moved on. Games were still available but the recent releases left me unimpressed. I focused my attention on playing older releases whenever I could. But I started hearing a rumour from magazines and video game TV shows, about this new Game Boy title made by Nintendo (no one ever mentioned Game Freak back then). A game where you explored a world full of monsters. You captured and befriended those monsters to fight other trainers, never fighting them yourself. I obviously knew that Nintendo and all my favourite video games were made in Japan but here was rare news about an exciting Game Boy title. The really crazy part, though, was that the game was a massive cultural phenomenon in Japan. The news and articles were saying that everyone was playing it. What? Everybody was playing a Game Boy game in 1996? It was unbelievable to my young brain. I thought I was the only person still playing the Game Boy on the planet.

You have to do a bit of mental work here, dear reader, to forget the existence of Pokémon. It’s not an easy thing to do. Pokémon is according to most metrics the most profitable media franchise ever.

You think the Marvel Cinematic Universe is bigger? Nope. They don’t have much reach outside the movies and TV shows themselves so it’s not enough revenue to compete.

Star Wars, with its forty years of associated toy sales? It’s not enough of a success outside North America, particularly in Asia, to compete. Star Wars is perhaps bigger than Pokémon in the US, but not worldwide.

Star Trek? The Pokémon trading card game alone is bigger than all of Star Trek at an estimated ten billion dollars in card revenue since its release.

Pokémon is simply the biggest media franchise ever, and it’s as relevant now all around the globe in 2022 as it has ever been. But there was a time before Pokémon was a global phenomenon. For a time, it was strictly a Japanese affair. The rest of the world could only stay outside, trying to look inside. And we’re not talking months here. Pokémon remained a Japanese phenomenon for two years. The rest of the world could only get an outside glimpse at the craze for a very long time. The trading card game, a Nintendo 64 game that allowed you to fight using the Pokémon from your Game Boy cartridge, a manga, the anime, even the first movie were all released before the Poké-phenomenom left Japan.

Pokémon was finally released in North America in the Fall of 1998, and it promptly flew over my head. I didn’t notice it was released. I was unaware that the Japanese phenomenon had finally crossed the Pacific. I didn’t even know they had decided on Pokémon as its English name. How could that be? Pokémon was released in North America along with the anime. It was everywhere. How could I completely miss this release? Before I answer that question, let’s move forward in time to early 1999, when I saw the best video game publicity ever made. Strictly based on this ad’s sense of humour, I decided to buy the game.

Strictly based on this ad’s sense of humour, I decided to buy the game.

Super Smash Bros. came out in April of 1999 and I bought it as soon as possible with my hard-earned paperboy money. Super Smash Bros. obviously features Pikachu, and even Jigglypuff, as playable characters. There’s a stage from the franchise as well, and you can even use Pokéballs. I immediately got very curious once I started playing. There’s a yellow electric rat constantly screaming his own name that’s given as much reverence as gaming Jesus, our lord and plumber, Mario. What was the deal with that? So I remembered all those rumblings about the pocket monster game, and figured that the game must be this Pokémon thing I was seeing in Smash. When I looked at the Works section in Pikachu’s character sheet, his single released game was there. That’s how old I am kids. I learned that Pokémon was released from the Super Smash Bros. character biographies.

That’s how old I am kids. I learned that Pokémon was released from the Super Smash Bros. character biographies.

I finally ended up seeing both the Red and Blue games at my local Zellers. How could I miss the media onslaught of Pokémon and being surprised at the presence of Pikachu in Super Smash Bros. ?

Because I’m Québécois. In Québec, the language barrier meant we got some stuff later than the United States and Canada. Big popular movies came out dubbed in French at basically the same time but books and especially TV shows were on a different timeframe as the rest of North America. An American TV show had to become popular enough to warrant shopping it around internationally, then it has to be licensed and dubbed by a TV network and only then can it be put on their schedule. Don’t go thinking that Québec always uses dubs made in France. A lot of French dubs for movies and TV shows are meant to be used internationally; they’ll use language understandable across la francophonie, and use a toned down Parisian accent informally called international French. These dubs are common in Québec for movies and TV shows but not all dubbing follows these constraints. Comedic and lighthearted content is better served by a local dub since it can more accurately reflect the local inflection and sense of humour.

Doing a cursory investigation tells me that Québec would usually get popular American TV shows a year later than in the US during the ’80s and ’90s, whether a French or Québec dub was used. That is if the show came to Québec at all.

But the overwhelming majority of video games were not translated at the time (publishers were finally required by law to offer French versions of their games in 2007) and would come out at the same time in both markets. This led to interesting situations in Québec. For example, the Capcom game of Chip ’n Dale: Rescue Rangers for NES was available before the cartoon was broadcast on TV. This was absolutely normal for me and all my friends back then.

As a final aside, the situation has changed considerably in recent times; I vividly remember being astonished in 2006 that the show Lost was broadcast in French on Radio-Canada only six weeks after the original version had aired on ABC in the US. Nowadays, the lead time for dubbed versions has been reduced even further. The greatest example is Game of Thrones, which was available in 170 countries on the same day during its last few seasons. On the other hand, most broadcast (ie. non-streaming) media still has some lead time before the release of its dub in Québec and other international markets. Depending on the property the French dub might be used, without a proper local Québec dub.

So why am I telling you all this? Because the Pokémon anime arrived in Québec in the fall of 1999, one year after the game’s release in 1998. I missed the media onslaught because there was no media onslaught. North America was not like Europe where companies would coordinate multiple localizations when releasing there. North America back then meant a strictly English release, with local Québec broadcasters left to fend for themselves. In the case of Pokémon, there was no anime release in the Fall of 1998. Nothing on Québec TV to convince you that Pokémon was a cool thing to like. The cable network Télétoon picked up the show and used the dubbing team from France who had their first episodes available in the Fall of 1999. Someone, probably at Télétoon, quickly realized that the French Pokémon names were inappropriate. The game and the trading cards were only available in English in Québec so we were already familiar with names like Jynx, and French names like Lippoutou were jarring. So instead of paying for a whole separate Québec dub, Télétoon had the Belgian dubbing team dub each sentence where a Pokémon name was said two times: one with the French name, and one with the English name. They would then assemble a specific version for Québec, and since the different lines were recorded during the same session, there was no difference in sound quality or anything. It was just as seamless as the version for France. I have never heard of anything like that ever being done for any other dub. It’s a thoroughly unique solution. This was particularly succesfull, so much so that in January 2000 the much larger broadcast network TQS starting showing the anime as well.

This situation made Québec the only region in the world to use the English Pokémon name in another language. Québec lost its specific dub in 2004, when the initial Pokémania was over. TV netowrks simply used the version for France. This means that Québec is also the only region in the world where the names of the creatures suddenly changed! With the now common practice of releasing games across North America in English, Spanish, and French, Lippoutou is now de rigueur.

Are There More Than 150 Pokémon?

Of course there have been more than 150 Pokémon for a long time, but were there more than the 150 Pokémon upon the initial release? And maybe more importantly, why does it even matter? It matters because there was indeed a hidden Pokémon only accessible through special events or outright cheating. This created an aura of mystery around the game. Since the original Pokémon is also riddled with bugs, causing all sorts of glitches to occur, players started seeing all sort of weird things they falsely prescribed to intended secret monsters.

That real hidden Pokémon was Mew, designed and hidden by Morimoto Shigeki the programmer of the game, as a kind of prank that only he could access and share with his colleagues. Mew was, of course, mentioned in the game (Mewtwo was in the game after all) but the creature was not meant to be seen. Once the rest of the team learned of the existence of Mew they started officially distributing the creature during events. This meant it was rare for Japanese players to receive a Mew and bred the interest in finding ways, fake or not, to catch Mew. Look up the legends surrounding the truck in Vermillion City. I remember having to hear all about that truck and feeling so bad for the people who wholeheartedly believed Mew was hidden under there.

Mixing into this desire for the real hidden monster, the game was riddled with bugs and bogus glitches allowed one to capture creatures that were the result of memory corruption. The most famous of these was MissingNo. and I remember schoolmates showing me the glitch all the way back in 1999. That sure didn’t help people differantiate truth from fiction; if you could catch a glitched Pokémon by surfing alongside a border of the map, why couldn’t you catch a Mew under a truck?

A year after the game’s release, idle theories and useful glitches, like the candy duplication trick, were already widely shared amongst players even in the depths of Lac-Saint-Jean.

Is the Game Any Good?

You’ve always had to bring your own fun into a Pokémon title. No hand-holding can change the fact that the core games have always been about deciding on your own what’s fun for you. Do you want to create an unbeatable team? What about playing through the story with a team of six Jigglypuff? Maybe you’re interested in collecting every monster? Perhaps your interest lies in the thrill of competing against your friends? Or maybe trading with your friends? Pokémon really shines when you can define an objective for yourself. I have only experienced Pokémon as a solo endeavour, with the goal of completing the game, since no one cared about it when I picked it up to help me spice things up. So it was kind of boring for me. Once the Pokémon anime hit the Québec airwaves, and a group of kids at school started playing the game during lunch, I had moved on.

If you pick it up in 2022, you’ll have a tough task ahead of you; you’ll have to figure out how to have fun with that game. It’s a difficult endeavour getting harder: I mean, Pokémon Legends: Arceus is right there, ready to entertain you effortlessly, albeit with terrible graphics.

Pokémon Legends: Arceus notwithstanding, every new adventure had been an improvement over the previous game, never a reinvention. So going back in time and playing the earlier titles is difficult. Perhaps if a feature you loved was removed there was reason to walk back the route. But nostalgia is the powerful drug that keeps people coming back to the first title. When they do, those people have to contend with so many irritants. For one, the game is excruciatingly slow. Everything takes forever. You walk slow, the menus are slow, the animations are slow, the text scrolls slowly, saving is slow. Nothing is fast, and the game feels fragile as a result. It feels like you can’t push the buttons on your Game Boy too hard or the game will break under the load. Considering the game is infamous for its buggy code it’s warranted. After all, they famously abandoned their old code base and rewrote everything when they released Pokémon Ruby & Sapphire on Game Boy Advance.

If you can get past the disrespect that game has for your time, which is a tough pill to swallow, you’ll find a quirky fun RPG with a wicked concept: no creature in the game is only an enemy. You can ultimately train and befriend your own Muk, or Lapras, or Zapdos. You can then use those monsters to trade and battle with your friends, using the connectivity afforded by the link cable. When it released, multiplayer experiences were far more niche than they are today. Online multiplayer, with services like Battle.net, were embryonic and riddled with issues and massively multiplayer online games were the purview of the committed few. The multiplayer concept was unique. No other game allowed you to trade creatures with your friends. Heck, even nowadays the concept is unique with nary a serious competitor to Game Freak in sight.

Conclusion

Only on Game Boy could Pokémon become such a large hit. The confluence of a large installed base with the ubiquity of the link cable made the gigantic hit a possibility. No other video game platform was as perfectly positioned to deliver the biggest media franchise in the world. That is what makes discussing everything around Pokémon interesting for me. I don’t believe for one second that Pokémon could have happened on Super Famicom or any other console. The core idea of trading monsters with friends would have needed a technological solution that Game Freak was incapable of developing since they were such a small studio. After seven years of Game Boy, Pokémon finally fulfilled the possibilities of the link cable. It was suddenly cool that portable consoles offered device-to-device multiplayer. Even today, the Switch is capable of playing a local game and trading monsters with another Switch next to it without any internet access needed. You can’t do that with two PlayStations or two Xboxes.

Another important aspect was the incredibly long legs of the concept. You couldn’t shake the idea that sequels were inevitable while playing the first game. Exploring Kanto, you could imagine other regions with other completely different monsters just outside the realm of your Game Boy screen. It’s not a surprise that an anime, a trading card game and other video games were easily developed once Pokémon hit it big: its concept is versatile and can be adapted to almost anything. Case in point, they made a Pokémon detective movie.

Finally, Pokémon made the Game Boy cool again, to everybody’s surprise. Game Boy hardware sales massively picked up once Pokémon was released. That meant that there was a renewed interest in the console. Around the world, old Game Boy development kits were cleaned of their cobwebs, and a massive amount of new titles started development. With the hindsight of years of experience with the platform, and the inspiration from Pokémon to innovate, the overall quality of those new games was surprising. The Game Boy went from also-ran to exciting within a year.

It also happened to be the only console where you could make a Pokémon ripoff, since no other popular system could allow trades between cartridges. All of that gave the Game Boy a renaissance that no console ever had, or ever will. The Game Boy was reborn thanks to those little insects walking up and down the link cable.

This article was first published on the .

This article was last modified on the .