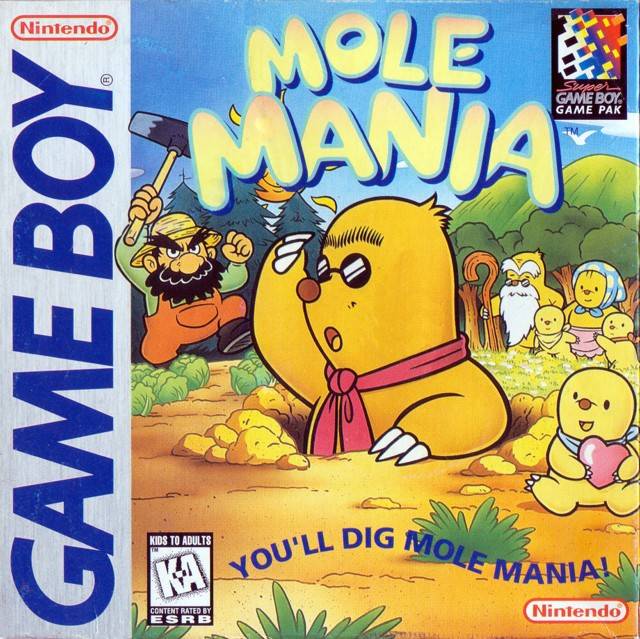

Mole Mania

- Japanese release in July 1996

- North American release in February 1997

- European release in 1997

- Japanese release in March 2000

- Developed by Pax Softonica

Buried Treasure

Gunpei Yokoi, the father of the Game Boy, was in a weird spot. He was the company’s oldest team leader at Nintendo but his reputation was shot. Inside the company he was seen as having lost his way, having spent too much of the company’s time and effort on a failed project with no appeal, the dreadful Virtual Boy. It was the epitome of his creed of using old technology in surprising ways (usually translated as Lateral Thinking with Withered Technology) but it lacked the fun factor that made Nintendo into a household name resulting in a very public failure for the company. Yokoi had planned on leaving Nintendo right after the release of the Virtual Boy. His interest in seeing the new console to release was the only thing keeping him at Nintendo. With that project a burning red failure, Yokoi stayed; he wanted to leave on a positive note, not in disgrace. To that end, he looked at the original Game Boy. It ran laps around the competition of portable consoles but all the media outlets were wondering why there was no new hardware. The answer was pure Nintendo: they were intent on maintaining the same principle that made the Game Boy a success of not compromising on battery life. Since there was no new CPU or screen tech that would provide a better experience while maintaining a reasonable battery life, Gunpei Yokoi tasked himself and his team with making a better version of the already existing Game Boy. This project would ultimately lead to the Game Boy Pocket.

While Nintendo kept the same muted, simple strategy for its portable behemoth, Game Boy games were getting rarer. To keep shelves stocked with good games Nintendo started their Players’ Choice program. The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening, Star Wars, The Bugs Bunny Crazy Castle, Mega Man: Dr. Wily’s Revenge are just some examples of games republished by Nintendo under their Players’ Choice banner. Clearly, the company was trying to put older titles of better quality on store shelves to maintain interest for the Game Boy and its new upgrade the Game Boy Pocket.

While in Japan Pokémon was out since February of ’96, the global future was uncertain. It was a truly gangbuster success locally that had given a second wind to the Game Boy but could this success be replicated outside Japan? Could Game Freak, an unproven group of young inexperienced people, provide more Pokémon games to solidify the mania? How long would people buy Game Boy systems to play Pokémon? Nothing was certain. Out of this weird middle age for the Game Boy, Game Boy Pocket was born. With that new console revision came one marquee title to coincide with the release, the fourth and final Nintendo EAD developed game for Game Boy: Mole Mania. A puzzle game pitting you as a mole that pushes and throws things while digging holes, the best way to describe it would be to compare it to the action puzzle games of the ’80s like Sokoban or Lode Runner.

I cannot say it loud enough: play this game! Mole Mania is very good. It’s a Shigeru Miyamoto masterpiece done during his golden age when his output was arguably at his summit. He was supervising classics like Yoshi’s Island and Super Mario 64 and here comes this game done in a genre that he had abandoned, and he brings all the lessons he learned since he last made an action puzzle game. It’s a true bona fide classic, and it’s absolutely forgotten.

A Hole Game

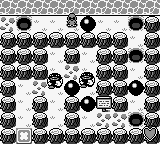

Since this is a top-of-the-line Miyamoto game all the bad things about action puzzle games are smoothed out. There are so many pitfalls the game could have fallen into but you can see they play-tested the hell out of the game to make it fun. Unlike Lode Runner, the enemies of the game stick to predictable patterns. They never run toward you, Terminator-style, making you run for your life every instant. Instead, you get in their way, because they follow a pattern.

There’s always a short way to reset a puzzle. Like Sokoban you can get objects stuck but there’s a very simple way to reset a puzzle. You just leave the screen and come back. A menu option also exists.

Every puzzle has the same solution: push the black ball against the rock blocking the path to the next screen. So you can fixate on getting that ball where it needs to go. There are multiple objects you can push but they always gravitate around getting out of the black ball’s way. However, the game often gives you more objects than you need. A pipe elbow will be pointless and irrelevant to the solution of the puzzle. Thus, puzzles are not always clean, meaning that you have more than what you need to finish it. On top of that, there are sometimes multiple methods to clear an exit. This is particularly apparent in level 4, where you have in quick succession multiple types of puzzles. So when reaching a new screen you immediately need to figure out whether there are objects that are useless to complete the level.

The game’s core gameplay is a throwback to games like Devil’s World and other early Famicom titles. Like those games it’s a single-screen affair, very interested in providing time-sensitive puzzles and filled with unbeatable enemies that need to be avoided. It’s a game that reflects back on the era when everybody was improving on the Pac-Man formula. Mole Mania should have happened in the ’80s when you look at its lineage and genre but everything else about the game is very 1996. The presentation is flawless, the game is littered with valuable secrets. It has boss battles and bonus stages and the ability to be played somewhat non-sequentially so you can come back later to a puzzle that stumps you. All elements that were common by 1996.

It feels like Miyamoto was thinking of an interesting project to do and saying I know how to do this effortlessly and he actually does. The presentation is as good as any mid 90s era SNES or N64 game with its distinct worlds, story told through the environment, and anime-inspired premise. Mole Mania is what happens when a developer goes back to older concepts and looks at those old tropes with their improved experience. Miyamoto knew how to push the contractors at Pax Softnica, with which he had already released two other Game Boy games, to refine the concepts until they were flawless, he knew how to remove anything superfluous so the game was easy to understand, and he knew how to build on his simple idea until it became delightfully hard while keeping its original core concept. Miyamoto in 1984, when he originally made games that look like Mole Mania was not that good. It might be my bias but I think Mole Mania is Miyamoto at his best. It was made in the same era as Super Mario 64, Nintendo EAD’s masterpiece. I can imagine a stressed out Miyamoto coming out of a difficult Super Mario 64 design meeting and going to speak to the people making Mole Mania afterwards to relax with something relatively simple. Something where he already knew how to solve the problems, where he wasn’t confronted with 3D problems he had no idea existed and still had to figure out. Imagine how much easier it is to work on Mole Mania when you spent the whole day trying to figure out how to control the camera in Super Mario 64.

Conclusion

The original Game Boy is at its best with this game; to me Mole Mania is a gift. I’ve adored Miyamoto’s trifecta of the late ’90s: Yoshi’s Island, which he believed to be his last 2D platformer, Super Mario 64, his success at inventing how to jump and explore a 3D world, and The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, the refinement of everything learned making those two other games. I thought I had played all his games made during that era, but here we have a fourth albeit lesser work done with the same talent by the same man and I had never played it. I can’t bring myself to finish Mole Mania; when I’m done I won’t have any games from golden age Miyamoto.

As a last aside, Mole Mania gives a great example against the concept of console generations to classify video games. Go read about video game history on Wikipedia for example or pick up any lesser book and you’ll be very quickly presented with this idea of console generations defining the whole industry. It’s everywhere, to the point where developers themselves constantly discuss their work in the context of generations. While generations can make some sense if only TV consoles existed, portable systems exist and are just as important. A game like Mole Mania and any Game Boy game released in 1996 is considered in the same goddamn generation as the Famicom released in 1983. Mole Mania was developed by Miyamoto concurrently with Super Mario 64. Both titles are brethrens, directed by the same man at the same time. No one should consider those games two generations apart. So that’s why I’m against the concept of generations, which is player-centric, while video games are made by artists. Artistic considerations and mindsets are more important than marketing categorization. Mole Mania embodies that idea perfectly.

This article was first published on the .

This article was last modified on the .