Tetris Blast

- Japanese release in March 1995

- North American release in January 1996

- European release in June 1996

- Australian release in 1996

- Developed by TOSE

A Blast Without a Bang

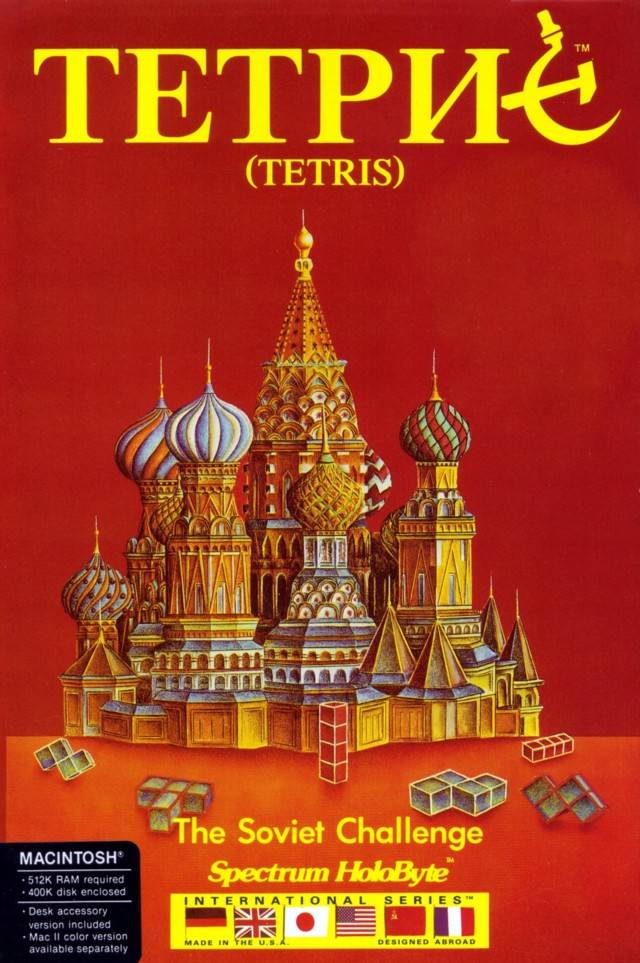

To get to 1995’s Tetris Blast, we need to go back half a decade. It is the summer of 1989, and the Soviet Union is clearly falling apart. Stretched to its limits by incessant military spending and its stagnant managed economy, what was supposed to be a reasonable political realignment finally broke the Communist Party’s ability to maintain power. Called Perestroika (Restructuring) and Glasnost (Openness), once these policies begin implementation, independence movements across the Warsaw Pact will start organizing. By the summer of 1989, a veritable wellspring of revolutions will start in just a couple of months across Eastern Europe, and the Polish people have already been allowed to vote in a free election, leading independent union Solidarność to enter the political sphere and to start breaking Communist rule in Poland. Tetris for Macintosh, released in 1988.

Tetris for Macintosh, released in 1988.

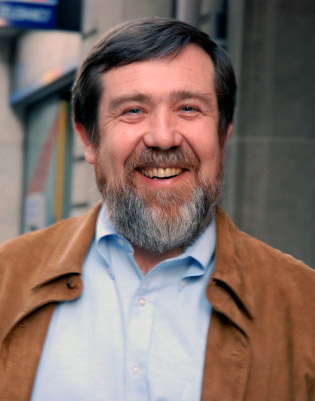

During this troubling era, Game Boy is released in North America and no one bats an eye that it comes with a Russian-themed game; it’s in vogue. The once evil Soviet populace is now seen as a group of oppressed nations yearning for freedom. Nintendo’s Tetris for Game Boy fits into this new narrative, with its imagery of the Orthodox Church, Russian folklore and Russian rocketry including the Buran spaceplane while not focusing on the CCCP regime. Less than six months after the release of the Game Boy the Berlin Wall has fallen and the Communists are undeniably on the way out. So there’s no reason to complain about a game with Russian iconography. They’re no longer the villains, they’ll soon be our friends. Ouf. Alexei Pajitnov. Credit Eunice Szpillman.

Alexei Pajitnov. Credit Eunice Szpillman.

The jovial Russian mathematician who created the tetrominoes game, Alexei Pajitnov, is making a new puzzle game about hats while this is happening. This is how he makes money in the video game industry, since he receives nothing from the licensing deals of Tetris. His former employer, the Soviet state, is cashing in all the dough and they are not redistributing the wealth his way. However, Pajitnov is already very well known for having created Tetris, which has quickly become a famous video game. So his new puzzle games are promoted with his name. It has a certain appeal; a puzzle game from the creator of Tetris must be fun! Welltris is being developed at the company that will become Spectrum Holobyte. He also starts working on Hatris and Faces… Tris III at his Dutch buddy Henk Roger’s company, Bullet-Proof Software. Just a year after the release of Hatris, Pajitnov leaves Russia to work for Sprectrum Holobyte in the United States. His credited work takes a nosedive, and he ends up joining Microsoft in 1996 to work on puzzle games there. Super Tetris

Super Tetris

During this time, licensees are making their own improvements on the Tetris formula but they don’t include classic modes in their games. While players have always enjoyed improvements on the classic formula and variants that spice things up, there is a fundamental quality with the original version of the game. Tetris has this magical feeling when played in its classic form. It’s visceral. It’s vital. It vibrates. Introducing bombs or weirdly shaped blocks changes its nature. It makes it into something else and if you just want regular Tetris a game like Super Tetris on PC and Macintosh is unsatisfying. It’s a problem because it can confuse consumers. Imagine you’re in a store, and the only Tetris version on shelves is Welltris. You’re stuck buying a heavily modified version of the original game. It might sour you on Tetris altogether.

This is a problem The Tetris Company has addressed since 1996. Since its creation, they have forced licensees to make sure a classic mode is always included. If you want to understand the magical qualities of a good bog-standard game of Tetris look no further than The Tetris Company’s own free online version of the game. It’s the reference version they show licensees to highlight their strict rules on gameplay and presentation, and Alexei Pajitnov has called it his favourite version of Tetris, hammering the point home that to him this is the correct one. Super Tetris 2 + Bombliss

Super Tetris 2 + Bombliss

Back in the early ’90s, Elorg, the original owner of Tetris’ copyright, is not concerned by any of this. They’re probably more focused on the survival of their state institution in this era of Soviet implosion. One licensee gets it though; Bullet-Proof Software. Remember, this is Henk Rogers’ company. He is a Dutch game developer living in Japan with the exclusive Tetris console licence in Japan. He publishes a series of games in Japan called Tetris 2 + BomBliss (for Famicom), Super Tetris 2 + BomBliss (for Super Famicom, PC-98, Windows, and Macintosh), and Super Tetris 3 (for Super Famicom). Those games all include variations on the classic Tetris formula but most importantly they also include classic Tetris modes as well. They’re also a hodge-podge in terms of development credits. The first Famicom game gives SEDIC the credit for the concept of BomBliss (later games credit APE, which must have bought them), Chun Soft is credited with the programming, and Japanese war crimes denier Sugiyama Koichi is credited for the music. Clearly, Henk Rogers knew how to make deals, his games have too many!

You might wonder why Henk Rogers has the exclusive console licence to Tetris in Japan, and Japan only? His genius dealmaking is responsible and if you have the time I would recommend watching the hour-long documentary Tetris: From Russia With Love from the BBC (it’s free on YouTube, don’t tell anyone!). You will learn the convoluted story that led us there. Let me try to give the short version:

- Robert Stein, a British software publisher, got a loose Tetris licence in 1988 that he sub-licensed to hell and back.

- Henk Rogers got the console rights for Japan from him, and when Hiroshi Yamauchi, Nintendo’s genius CEO, asked Rogers to get them the worldwide portable console rights, Henk Rogers got fed up with Stein’s stalling and flew to Moscow.

- He finagled his way to a meeting with Nikoli Belikov, the Elorg employee assigned to the Tetris licence. He showed him that Stein had sub-licensed Tetris for consoles, while Belikov believed Stein’s licence only covered computers.

- Belikov then had Stein sign a tighter deal clearly limiting his licence to computers with screens and keyboards. Because Stein was also in Moscow, by happenstance, at the same time.

- Belikov afterwards hitched his wagon to Henk Rogers. Belikov maintained Rogers’ exclusive Japanese console rights, and gave Bullet-Proof Software portable rights, which was then sub-licensed to Nintendo.

- Rogers also got Nintendo of America the console rights in North America for good measure.

Alexei Pajitnov, Henk Rogers, and Hiroshi Yamauchi. Credit Henk Rogers.

Alexei Pajitnov, Henk Rogers, and Hiroshi Yamauchi. Credit Henk Rogers.Henk Rogers made friends with everybody important. He was a personal friend of Hiroshi Yamauchi, probably the only westerner to ever befriend the genius Nintendo CEO renown for his stern personality. Henk Rogers made friends with Tetris creator Alexei Pajitnov and later went into business with him. Without a doubt though, his greatest accomplishment in friendship-making is with Nikoli Belikov. He was the taciturn Soviet technocrat Elorg tasked with reviewing the licensing agreement they had with Robert Stein. They were never chummy, but they were seeing eye-to-eye and trusted one another. Faces… Tris III

Faces… Tris III

The traditional story of how Henk Rogers outmanoeuvred Robert Stein always disregards the most powerful tool in Henk Rogers arsenal; cold hard cash. A Tetris computer licensee can expect to sell from 10,000 to 100,000 units of their computer Tetris version for 40 to 50 bucks. Generously, that’s in the ballpark of 5 million dollars in revenue, not profit. You need to pay for development of the game. Then you need to pay for production of the disquettes (or tapes) and the box with all the printed material. You’re not done! You need to distribute the game. It’s expensive to truck carboard boxes across the world. You finally need to pay for advertising and marketing to let people know you have a game. Licensees could expect to give the Soviet state maybe half a million dollars for a gangbuster success if their deal was for 10% of profits, and I’m extremely aggressive on the terms. It makes no sense that Robert Stein signed a deal worth 10% of profits. I would presume he had something more generous than what Nintendo ultimately signed.

In the console world, Henk Rogers’ negotiating hand was full of unbeatable cards dealt by Yamauchi. He, and his card company turned toymaker, had already bet on selling millions of Game Boy consoles. The Famicom was a global success, Nintendo was very confident in its ability to market and sell Game Boy so they were willing to commit a lot of money upfront. The plan was already conceived to ship Tetris with every single Game Boy outside Japan. That’s probably why they sent Rogers instead of going the usual corporate route; they very quickly needed the rights and were willing to pay Rogers handsomely if he could make the deal happen quickly. For the North American console rights (according to the BBC documentary From Russia with Love) Nintendo of America paid $500,000 upfront and committed to 50 cents per cartridge sold. For the 8 million copies of Tetris on NES sold, that’s 4 million US dollars they sent to Elorg. I can’t find the exact terms for Tetris on Game Boy, but it’s very possible Nintendo paid a million or two upfront and the same 50 cents a copy. With a reported 29.72 million manufactured copies of Tetris on Game Boy including bundles and separate sales, that’s potentially 15 million US dollars for Elorg for the Game Boy version of the game. Maybe the deal was for less than 50 cents per copy, but I don’t know why Elorg would have agreed to lower terms for Game Boy. If anything the fee might have been higher. I don’t see how Robert Stein, with all his useless British bravado and futile attempts to get Gorbachev to intervene, could rival the millions of dollars Yamauchi was able to guarantee.

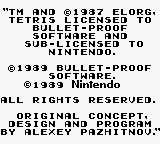

And through all of that, when starting every Game Boy copy of Tetris, the first words you see are: Tetris licensed to Bullet-Proof Software and sub-licensed to Nintendo. Henk Rogers was making some money with every copy of Tetris. Not bad for one trip to Moscow on Yamauchi’s request. Henk Rogers’ work as a matchmaker, credited on every copy of Tetris for Game Boy.

Henk Rogers’ work as a matchmaker, credited on every copy of Tetris for Game Boy.

Henk Rogers & Nintendo

Henk, like I said, uses his Japanese licence in the ’90s, after his return from Moscow, to make a series of improved games. They’re called Tetris 2 + Bombliss, Super Tetris 2 + Bombliss and finally Super Bombliss 3. But there’s one company who fundamentally does not get the need to offer a classic Tetris mode.

Nintendo.

That’s right. They immediately understood that Tetris would make Game Boy a global smash hit. But they didn’t understand that all copies of anything called Tetris should offer a classic mode. With Tetris 2 and Tetris Attack, Nintendo treated the word Tetris like it simply means falling-block puzzle. They commissioned completely new falling-block puzzle concepts and called them Tetris something. It’s also indicative of Nintendo’s development strategy. Every Game Boy already has a very good copy of Tetris. Outside of Japan, everybody who bought a Game Boy already owns Tetris. Why spend so much time and effort to redo the same thing twice? That’s Nintendo’s approach for you. They’re a smaller software company than you think. Managing their small amount of resources is vital. If Tetris is already available on Game Boy, they don’t want to reimplement what they’ve already done. They need to provide new experiences to stay relevant with their small headcount. A great example is the Nintendo developed Tetris DS. It was Nintendo coming back to Tetris in 2006 after leaving the franchise to other companies for 8 years. It’s the most impressive Tetris game due to its inventive game modes: it’s chock full of new twists on the good old Tetris formula making it a great game to buy and play. You’re getting a ton of new stuff and a great classic mode taking you on a tour of NES nostalgia. That’s how Nintendo develops and markets their games. They made Tetris DS because there was no version of Tetris playable on DS, and they worked really hard on creating new experiences to convince everyone to buy Tetris all over again. It also had a classic mode mandated by Pajitnov and Rogers’ The Tetris Company and it follows the Tetris guidelines to the letter.

But back when Nintendo held the Tetris licence in the ’90s, there was no standardized licensing rules. They had the US console licence so they used it with unrelated puzzle games to gin up their marketing. Tetris Blast to me is the final nail in the coffin; it’s a portable version of the BomBliss concept from the nice people at Bullet-Proof Software but without the accompanying classic mode they put in all their other releases. That stings.

Blast Off

Clearly, there was value in bringing the successful Tetris + BomBliss franchise from Bullet-Proof Software (BPS) to Game Boy. A Game Boy is a perfect, dare I say magical device for puzzle titles. There’s just one little problem; while BPS technically owns the portable Tetris licence, they had sub-licensed it to Nintendo. So it’s really Nintendo that owns the worldwide portable licence for Tetris. This next part is a guess but I bet I’m right about this. Bullet-Proof Software released Super BomBliss on Game Boy in Japan without any Tetris intellectual property. The name and the original Tetris concept is not on the cartridge. You can play Bombliss, but not Tetris. The tetrominoes, the blocks themselves, and the falling-block puzzle idea are not copyrightable concepts so it’s ok. It’s very much a sequel to Super Tetris 3 for Super Famicom. Only the original creation of BomBliss was on the cartridge, bypassing the need for the portable Tetris licence. Nintendo of America then liked Super BomBliss enough to bring it over to North America without major changes. They picked it up for publishing and just like they had done with Tetris 2, they slapped the Tetris brand name on the game for good measure. So that’s my theory of how we ended up with Super BomBliss in Japan without Tetris, and the same game in North America with Tetris in name only. How infuriating, and confusing!

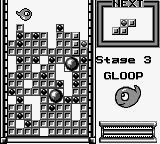

Since a puzzle game lives and dies by its gameplay, how is Tetris Blast/Super Bombliss? It’s OK. It offers a different take on the tetromino game, with a focus on bomb blocks. Completing a line detonates the bomb blocks within that line. If you don’t have a bomb block, completing a line does absolutely nothing. All the blocks just stay there.

Since you’re forced to focus on bomb blocks, their detonation range becomes vital to success. Joining multiple bomb blocks together multiplies the range of the later blast, so you work hard to create the largest pile of explosives possible. Unfortunately for me, I’m never sure what size a blast will have. I still don’t get the compounding rules when multiple bomb blocks detonate together. It’s too complicated for my simple tastes.

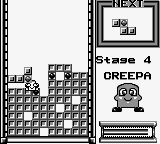

On the options side, the game has a two-player link cable mode that no one ever played because you need two cartridges, and three single-player options. A strangely named Training mode, which ends up being the endless chase for a high score we all know and love. A Fight mode, where characters appear above your play field and do all sorts of aggravating things. They push blocks, make them fall faster, spawn even more, etc. Once you’ve completely cleared the playfield of blocks, they are defeated and you move on to the next fight with a different creature.

Finally, we have the meat of the game, and the first mode on offer: Contest. Providing a large list of stages to clear, each is a pre-populated screen of blocks with a difficult setup. You have to simply clear the whole screen of all the blocks, but the challenge comes from the sometimes vicious way the initial blocks are placed. You can play this mode for a long time, and it uses passwords to restore your progress.

Tetris 2 2: The Sequel to the Fourth Tetris 2

Before we finish this article, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention Super Bombliss DX, the Japanese-only sequel to Super Bombliss. It’s not much of a sequel, featuring a simple colorized version of the original Game Boy title. To juice up the offering the game now includes a puzzle mode, featuring screens you have to clear with only a limited set of predetermined falling blocks.

Conclusion

Tetris Blast is fine. My only complaint about the game is its North American title: they should have released it as Super BomBliss over here. A final interesting element is that Henk Rogers and Nintendo had already signed a very similar deal for another game in 1992, three years prior. It had a similar-ish story: BPS wanted to bring to consoles a puzzle concept they had bought from someone else, and Nintendo liked the concept enough to put one of its brands on it. Unlike Tetris Blast, the marketing was better cooked. We’ll look at it next.

This article was first published on the .

This article was last modified on the .