Game Boy Camera

- Japanese release in February 1998

- Japanese release in February 1998

- North American release in June 1998

- European release in 1998

- Developed by Nintendo

A Camera in Your Pocket

Where is the closest camera you own right now? In your pockets? If you’re reading this on your phone, you have a camera looking at you right now, and a whole family of high-quality sensors on the back of the very device with which you’re reading this article. The ubiquity of cameras has thoroughly changed our society, from personal communications to police oversight. The Game Boy Camera came out at a time well before that revolution when a photograph was still an event. The closest peer to this accessory in terms of size and price in 1998 were disposable cameras. Costing $10 or lower, disposable cameras were a democratizing force for the camera world. They allowed you to enjoy photography for a very small initial investment. However, they did not change the fundamentals of film cameras; you needed to pay for film development for all the pictures you took, even for duds you were going to throw away.

Digital cameras were already available in 1998. With their rewritable media, they allowed you to take and delete an infinite number of pictures. You were limited only by your digital storage space. In 1998 most cameras saved their pictures on 3 & 1/2-inch diskettes, which meant you could carry a stack of them with you. However, the Sony Mavicas sold for around USD $800 at that time; an expensive sum for very low-resolution pictures. The Game Boy Camera is a peer of those early digital cameras. It was unique amongst digital cameras for its very low price, which came with absurd limitations that severely limited its appeal. We’ll discuss this fascinating Nintendo device in detail, and together we’ll discover what motivated the employees at Nintendo to make the Game Boy Camera.

A Greyscale Camera

When Gunpei Yokoi left Nintendo, Hirokazu Tanaka felt betrayed by his departure, and wanted to prove that people at Nintendo could still apply his lessons to create inventive products. The Game Boy Camera and its printer were born of this desire to show the creativity of the developers who stayed with Nintendo. Yokoi accidentally died before the camera was released, and his thanked in the credits.—Translated from L’histoire de Nintendo Volume 4, P. 153.

Gunpei Yokoi is best remembered as the father of the Game Boy, since he was the leader of R&D1 where the device was developed. When Yokoi left Nintendo in the mid ’90s, Hirokazu Hip Tanaka, a music composer inside the company, saw the Game Boy Camera project as a way to prove his and his colleagues’ worth. They had the engineers to develop future iterations of the Game Boy, but they had lost their superstar toymaker. Yokoi was famous for his work at Nintendo; a rare privilege only bestowed back then upon him and Shigeru Miyamoto. Miyamoto was a video game developer but Yokoi was something else entirely. He was an engineer and an inveterate tinkerer. Ultimately, he was Nintendo’s star toymaker. Yokoi had started at Nintendo when it was still a playing card company, and his wonderful designs gave Nintendo a solid footing when it diverted in toymaking. The stories around Yokoi’s mechanical creations were legend. With Yokoi’s departure, the R&D1 division was further divided into a hardware and a software section. Okada Satoru was put in charge of the hardware, and no one internally could doubt his ability to deliver good products, since he was the person who defined all the important details of the Game Boy. An engineer who started at R&D1 working for Yokoi, he went against his boss during the Game Boy’s development. Yokoi wanted the Game Boy to be similar to a Game & Watch that would be popular for a season. Perhaps a machine that could only play a limited set of predetermined games. Yokoi had the mentality of a toy-maker; he focused on building toys that would grab children’s attention for a moment before they moved on to something else. It was Okada that wanted a hardware platform that developers could fully program. Something where our waning attention is focused on the cartridges, not on the hardware. Simply put, a portable Famicom. Yokoi relented and let Okada build the Game Boy his way. This highlights the trustworthiness and competence of Okada; he would continue to deliver portable success after portable success until his retirement from Nintendo in 2012. Back in 1998, he had not yet proven himself, and was certainly not known for his toymaker mentality. Making a digital camera for the Game Boy might prove that Nintendo R&D1 could still make interesting toy-like accessories without Yokoi.

Limited Hardware

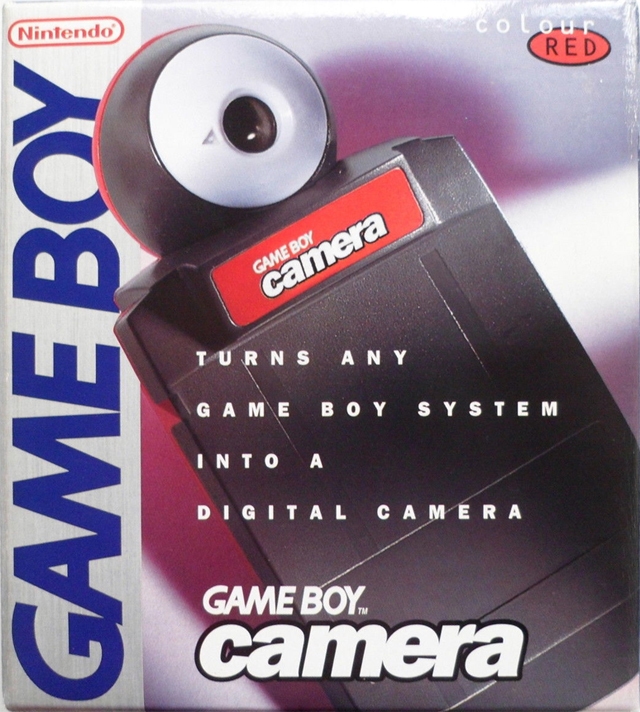

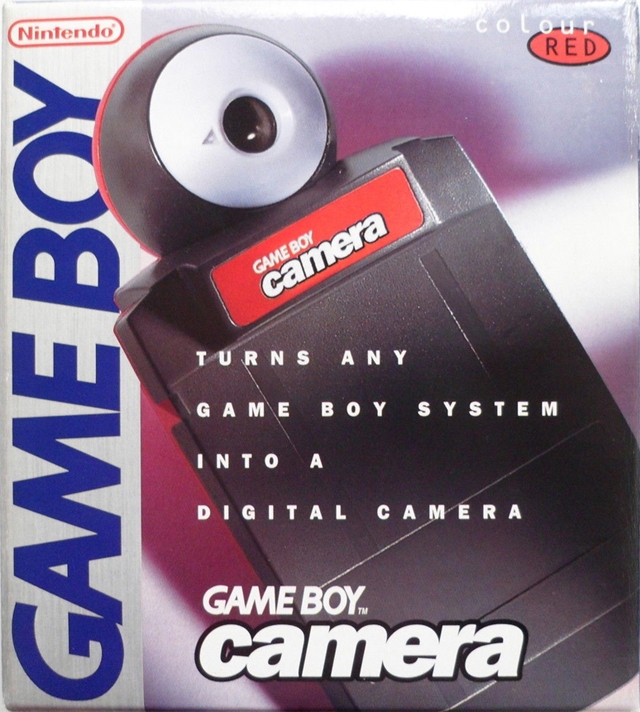

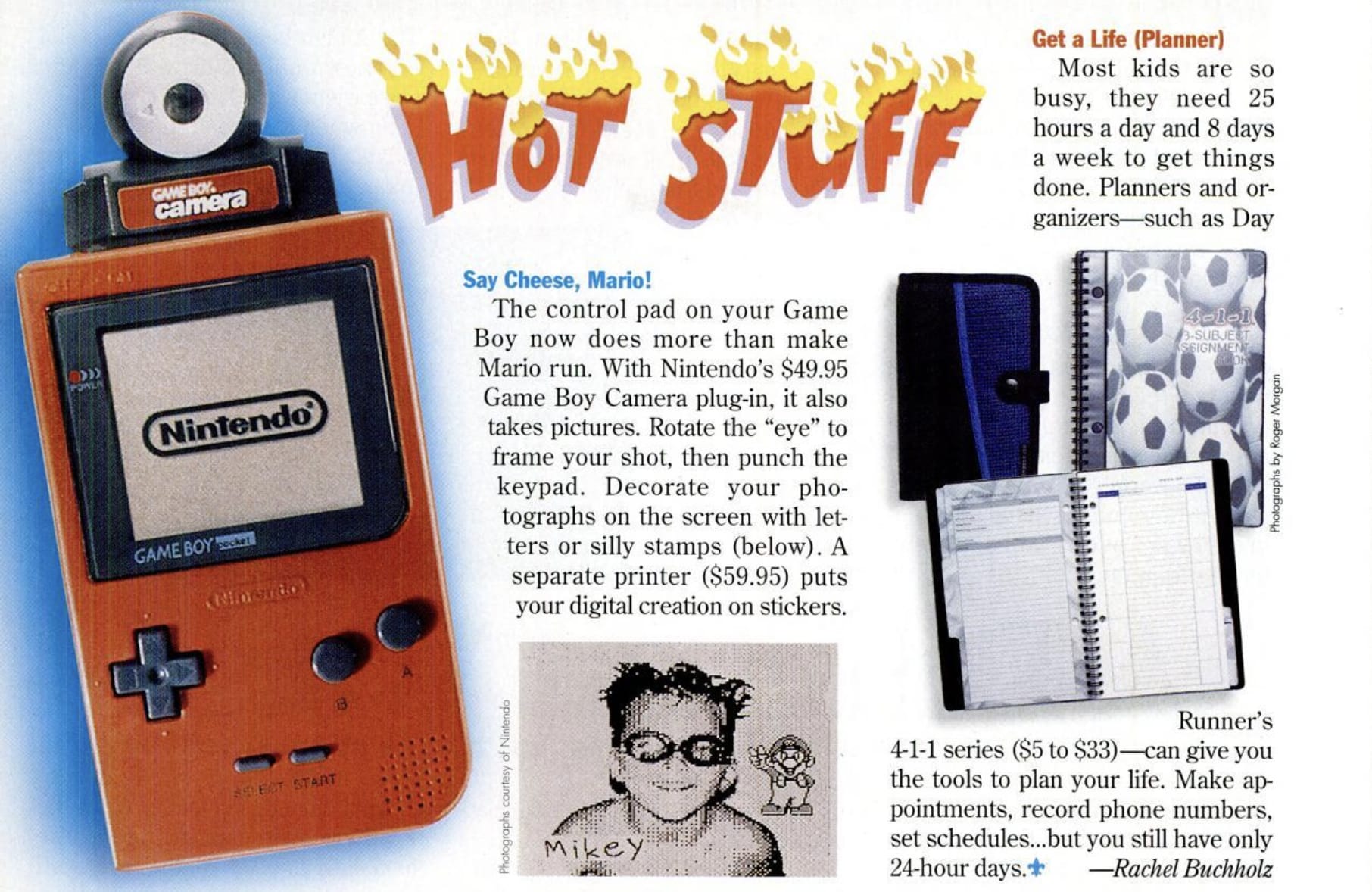

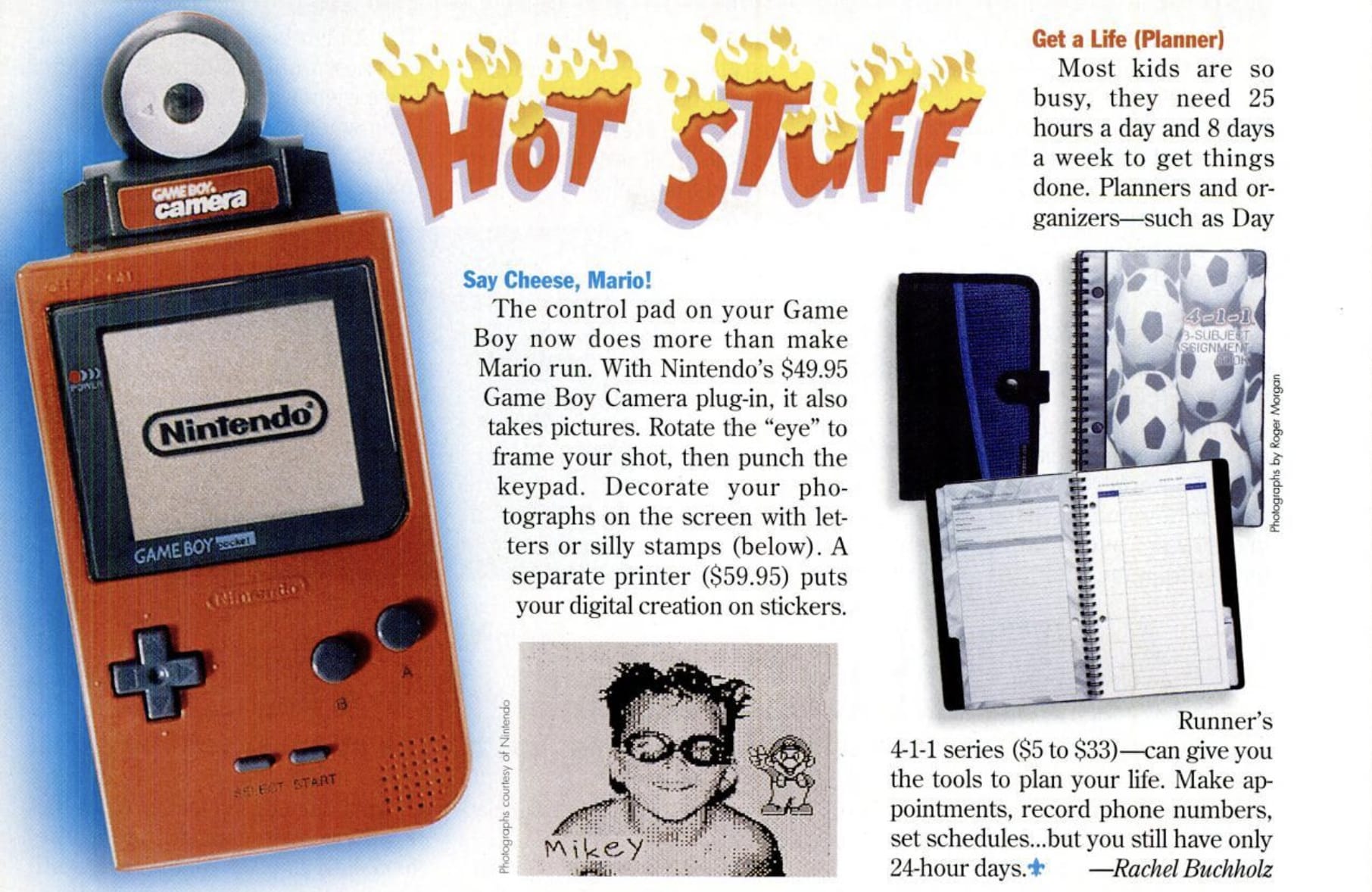

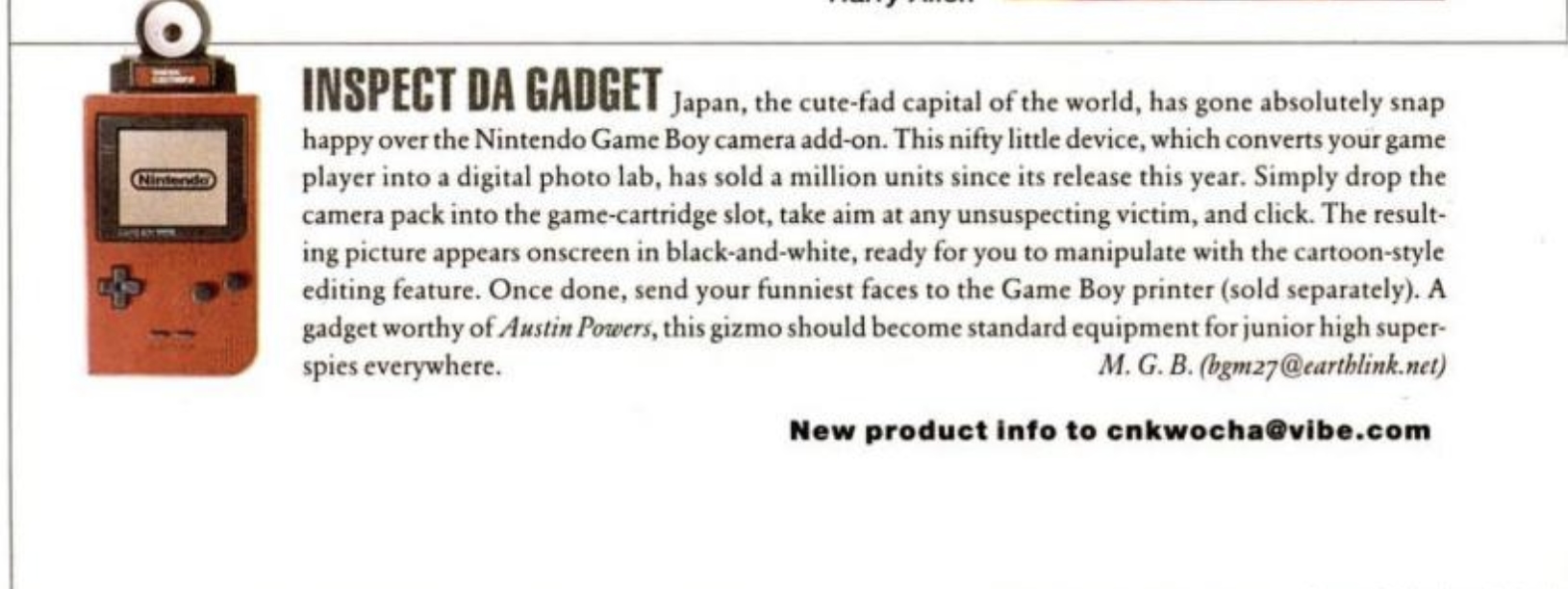

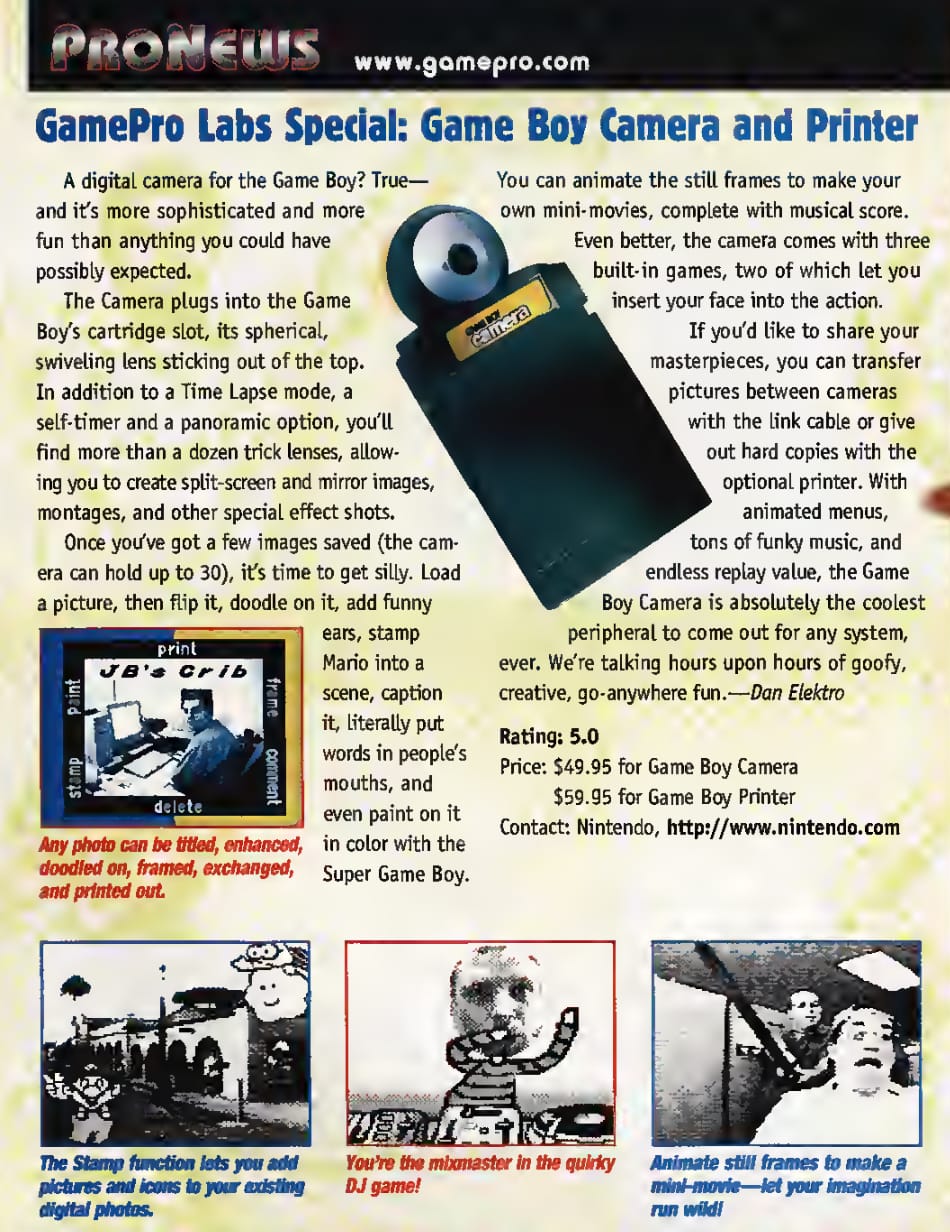

With our modern point of view, Game Boy Camera is a complete joke. It can seem like no one could tolerate its low image quality and that it must have been a monumental flop. The reality is far from that. Looking back at the Game Boy Camera’s release in 1998, the device enjoyed a somewhat warm reception. Popular Science, July 1998, p. 12

Popular Science, July 1998, p. 12 Boys’ Life, September 1998, p. 11

Boys’ Life, September 1998, p. 11 Vibe, August 1998, p. 148

Vibe, August 1998, p. 148 GamePro, August 1998, p. 30

GamePro, August 1998, p. 30

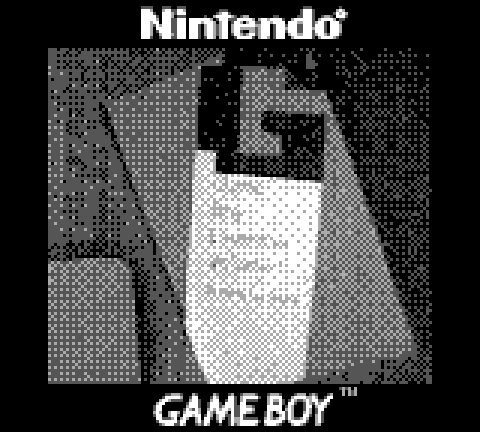

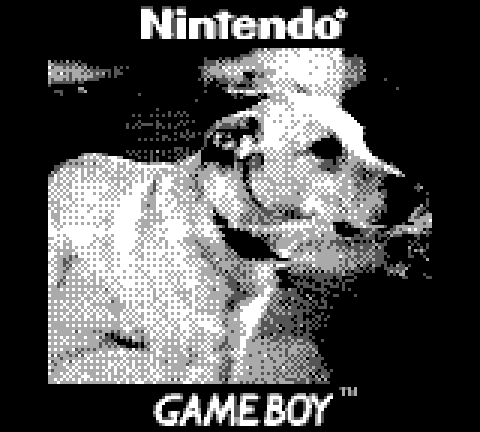

Yes, the pictures it takes are laughably bad, with a ridiculously low 128 by 112-pixel resolution. The thing is only good at taking pictures of large things (like a head or a dog) from way up close. Don’t even try to take a picture of a distant landscape view. To top off the mediocrity, pictures have no colour, being only available in the same four shades as your Game Boy. However, you have to look at what digital cameras were capable of doing and at what price to understand the device’s appeal in 1998. Of course, something like the Canon EOS D2000 existed, but this 1728 by 1152 resolution professional device retailed for over $15,000 USD. It was also a bleeding edge trailblazer; it was the first digital camera somewhat respected by professionals. We have to look downmarket to find peers of our little puny Game Boy Camera. For example, Minton made a crappy OEM camera that was re-badged by countless companies. It came with a 640 x 480 pixel sensor and sold for around $149 USD. It’s a much better device at three times the price but it is still a terrible camera compared to modern standards.

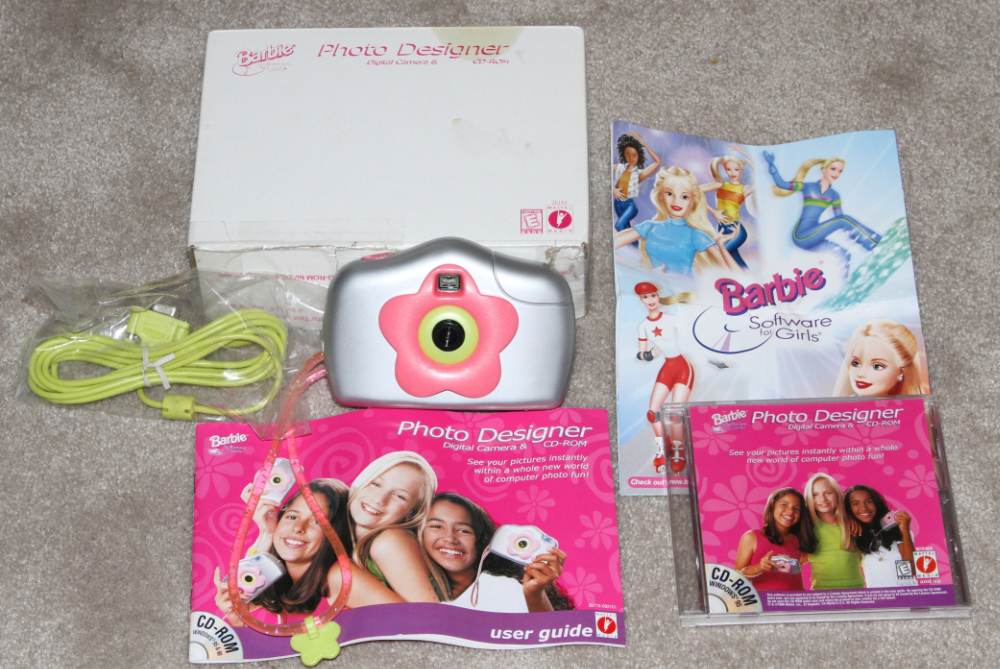

When you look at it, the Game Boy Camera is more akin to a toy than a digital camera. We’re lucky, we have a new camera toy from 1998 to compare it against. BarbieCam!

BarbieCam!

Barbie Photo Designer was announced in September of 1998, obviously for the upcoming Holiday season and was a package consisting of the digital camera and its accompanying PC software. It retailed for $69.99, a shockingly low price at first glance for a digital camera and PC software. Upon closer examination the device is not too good to be true. Although it took colour photos, it is very close to the Game Boy Camera in terms of resolution: 160 by 120 pixels. That’s minuscule. An example of a BarbieCam photo. This photo was taken with the later Nickelodeon model, which is the same camera. Photo courtesy of Superkids.com.

An example of a BarbieCam photo. This photo was taken with the later Nickelodeon model, which is the same camera. Photo courtesy of Superkids.com.

It was a severely limited device. It’s a digital camera but it doesn’t have a screen or removable media. All the beautiful benefits of digital photography come from those two things. Without a screen you can’t know if the picture you took is any good and without removable media you can’t keep taking pictures by swapping SD cards or whatnot. You’re stuck with the six pictures it can keep in its internal memory.

The device’s only options are taking pictures or deleting all the meagre six pictures without ever looking at them. Once you connect to a PC, you can very slowly transfer your pictures and finally see them for the first time. I imagine most kids ended up using the device in their home fairly close to their PC due to those extreme limitations.

Moving on to the software, both companies chose to focus on offering games with the pictures you took to complement their low-resolution cameras. I guess there aren’t many ways to make a bad quality camera fun. When you compare the disadvantages of Barbie Photo Designer and Game Boy Camera, that’s where you understand that the portability, viewfinder and memory for 30 pictures make the Game Boy Camera a competitive package in this brand new toy camera category. This category was hotter than you think as well: Barbie Photo Designer sold 300,000 copies in the US in its first year on the market and the Game Boy Camera sold a million copies in Japan. However, the market would quickly get saturated with copycats, and by the mid-2000s digital cameras had come down in price enough that a toy digital camera became a niche item. Parents seemingly bought their kids cheap full-fledged cameras instead.

Terrible Software

I’ll say it upfront; I don’t like the Game Boy Camera software. It’s a mess. It features so many baffling interface decisions. People have called it quirky. I have a different word for it: bad. The Nintendo Game Boy Camera Funtography Guide provides a full map of the software.

The Nintendo Game Boy Camera Funtography Guide provides a full map of the software.

You can immediately see that there are a lot of things you can do. Outside of Mario Paint, I can’t think Nintendo had ever made a user interface this complex before.

Upon starting the device, you’re presented with a start screen with photos of someone in a Mario costume. This shows one conceit of the software; that it will sometimes use real photos taken with a Game Boy Camera. It’s not a full design choice. Large sections of the interface use drawn art to represent characters. If you get an idea like that, I’d expect them to use it fully.

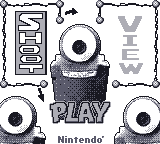

We get a complete rookie mistake on the main screen of the interface: they never indicate you can press the Start button to access settings. So on a screen with three clearly written choices, you actually have four. Let’s jump into the worst segment of the device; Play. When you go into this segment, a game of Space Fever II immediately begins. Two enemies drop down from the top of the screen, with letters written on them. Now, those enemies are actually the selection method for the other games you can play. So if you shoot those lettered enemies, you start another completely different game. However, if you shoot none of them, or miss your shot, Space Fever II will begin. Imagine that; a selection menu with a time limit. Upon starting those other games, you get astoundingly different screens to navigate their respective options. There is no general logic. The whole UI is a mad house.

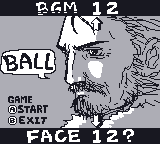

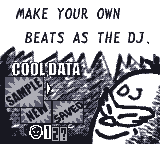

The first game is a copy of the first Game & Watch title, Ball. We’ve discussed it previously when talking about Game Boy Gallery. This version is using different sprites for the body, and allows you to use pictures for the face. The second game is a small DJ toy that I cannot understand for the life of me. The final game, which you unlock upon completing Space Fever II, is a running game where you mash buttons. Once again, you can put your face on the character you play. The Shoot menu

The Shoot menu

Upon going to the Shoot segment, you get what is supposed to be a parody of an RPG’s battle screen, with pixel art of people standing in as your enemies. Since you just came from a screen where someone in a Mario suit was dancing about, the joke falls flat immediately. The battle screen includes a run command, leading to an infamous joke played on the user. What are you running away from? BAD UI!

What are you running away from? BAD UI!

That jokey screen is meant to tell the player that they can’t run away, this isn’t an RPG, just a parody of one. But the very real face has those hideous drawings added on them. It’s just so out of place.

The two most sedate and reasonable segments of the software are the viewfinder screens and the photo album under View. The picture taking features all the controls around the viewfinder, arranged in an intelligent manner that focuses on quick adjustments. The photo album navigation is pretty straightforward, and once you reach the single picture view, all the options are also arranged around the picture. If you dig deep enough, you can find drawing tools that provide you with a barebones Mario Paint. You could take a picture of a white wall and just draw on your Game Boy. You don’t get the benefit of a mouse, but it’s a fun, well designed little drawing utility in a sea of terrible UI.

The camera has far more tricks up its sleeve, and they are all bespoke tools that are hard to grasp because their user interface is not standardized. All in all I think part of the mess is explained by the number of companies who worked on the project. Employees from Creatures (formerly Ape), Game Freak, and R&D1 are all credited. This is a complete guess, but I think employees completed different segments of the software alone and those were added together with no regards for consistency. Even Jupiter, the company mostly known for Picross, is thanked in the credits but they might have supported in other ways like Quality Assurance. None of the craziness in the software was featured on the box; the box is very sedate, even in Japanese. The ads themselves, in both Japan and the US, focus heavily on the power of easy photography (duh) and the fun that can be had with the stamps implemented in the painting tools of the photo album.

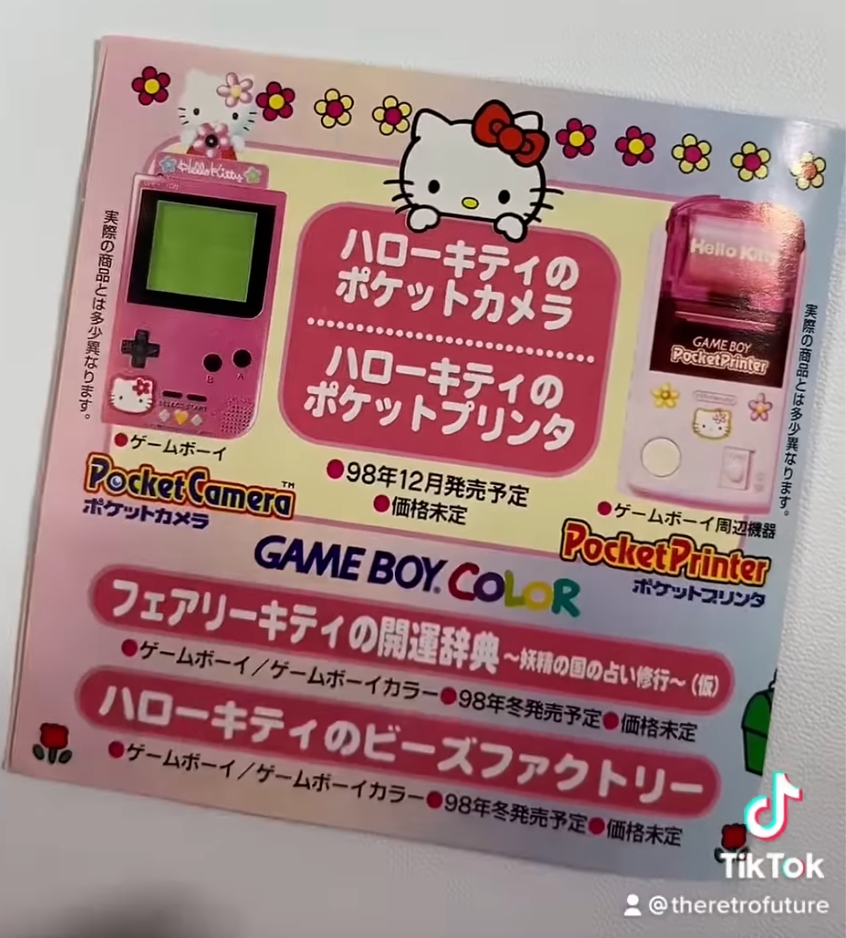

We got a surprising revelation just recently in 2020 that highlights the poor user interface design. As a part of the Gigaleak, a massive lotcheck of Game Boy titles was uncovered. Lotchecks, in internal Nintendo parlance, are lists of ROM ready for use in cartridges. They’re the golden masters. Amongst this lotcheck was Hello Kitty Pocket Camera, a special version of the camera dedicated to whom else but Hello Kitty. This whole special version of the Game Boy Camera is 100% complete, yet was never released. No one outside Nintendo had seen this software before 2020. When you load up this golden master in an emulator you can see all the beautiful differences. While all the camera functionality from the released version is present, nothing from the released Game Boy Camera user interface was reused. I’m not versed enough in Japanese to explore the interface in detail but my cursory look revealed a much improved UI. For example, if pressing Start sends you to another screen, you see a mention from the Hello Kitty UI. All the creepy pictures and inscrutable in-jokes have been removed. It’s clear the Hello Kitty UI was their second attempt at a Game Boy Camera interface, and this second crack at the problem gave them enough time to finally make a workable interface. It’s just a shame they never released it. We know what the hardware could have looked like from a Pocket Hello Kitty flyer.

We know what the hardware could have looked like from a Pocket Hello Kitty flyer.

Game Boy Camera Gets a Receipt Printer

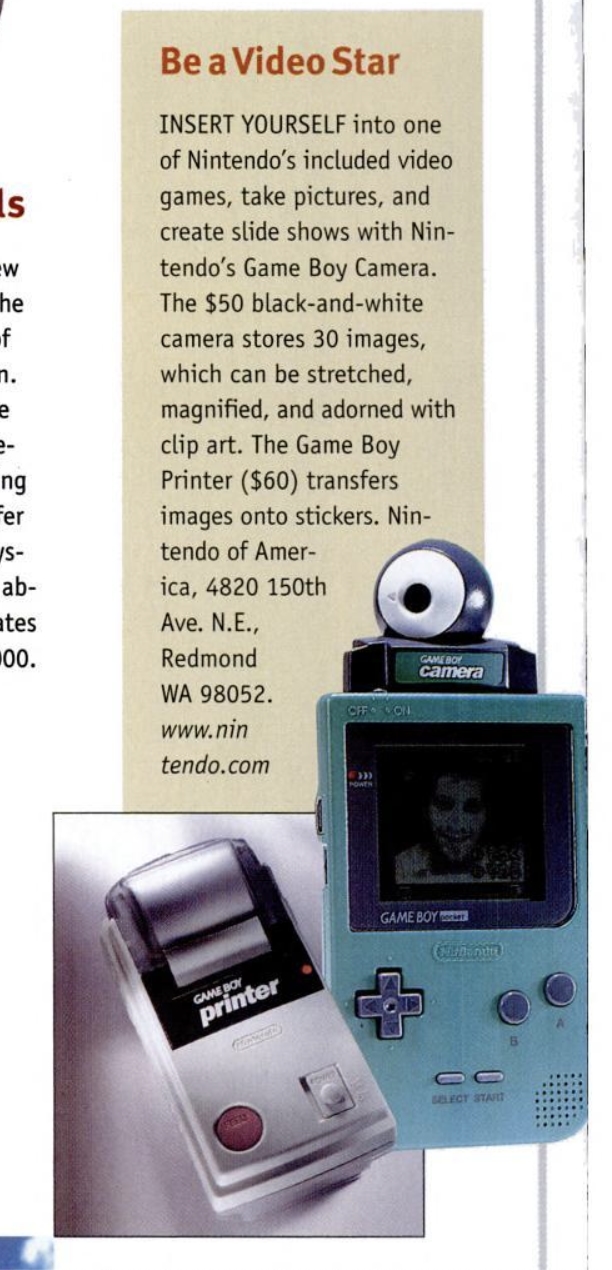

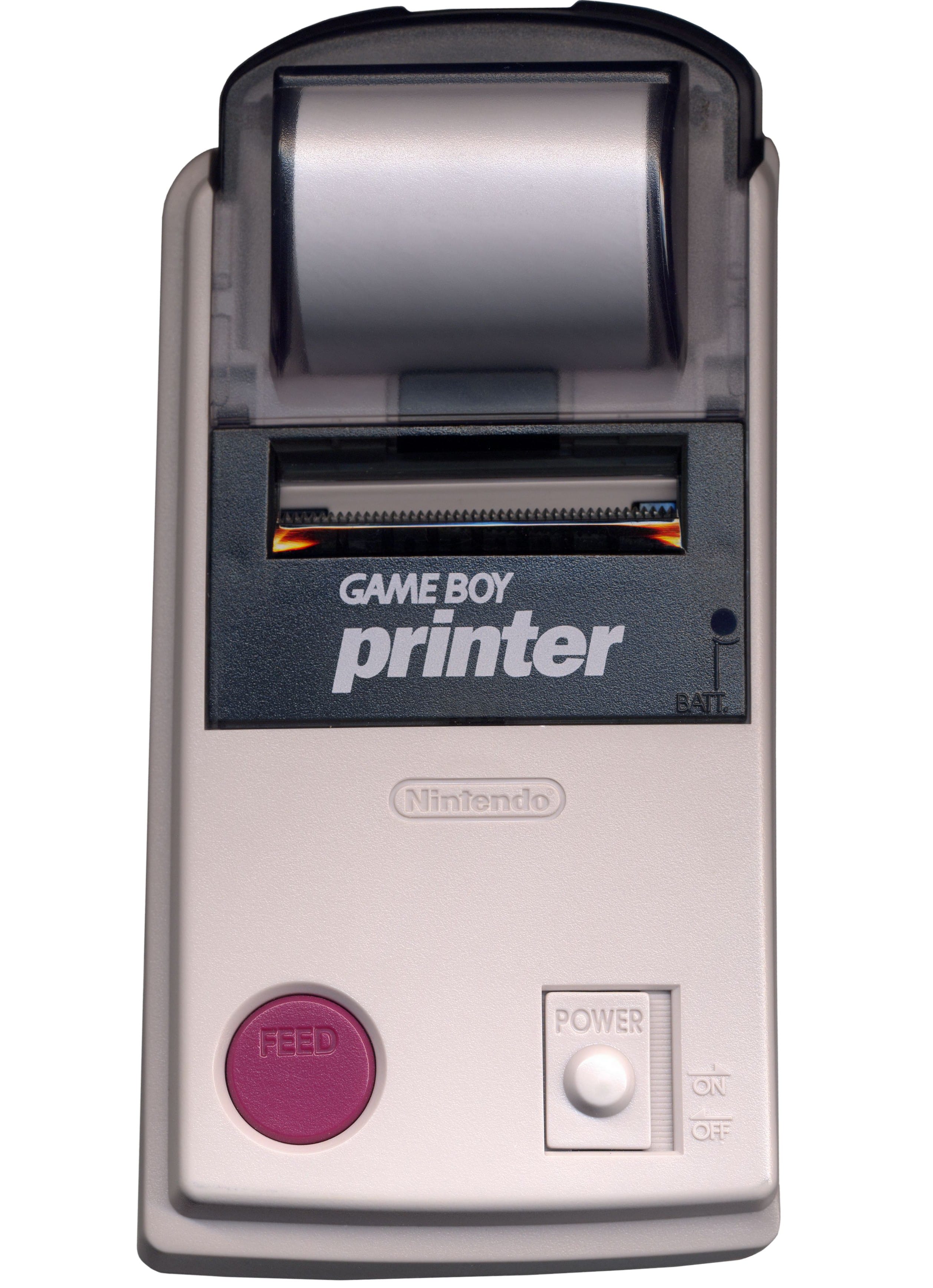

Nowadays, people are satisfied that their photos live online, but in 1998, everybody expected to get printed copies of every picture they took. You could trade pictures with another Game Boy Camera using a Link Cable, but keeping your pictures imprisoned inside a Game Boy Camera was a non-starter; Nintendo wanted to provide printing capabilities. While Nintendo could have answered with a stereotypically Japanese solution by putting printing kiosks in combinis all over Japan, leaving the rest of the world to fend for itself, they instead developed a portable printer one could easily buy alongside the camera. This was a great idea in practice, and a marked improvement over Mario Paint. I feel like Mario Paint never reached its full potential because it never had any print capabilities outside of record your art on a VHS tape and figure something out from there. The Game Boy Printer.

The Game Boy Printer.

So as with the camera came the Game Boy Printer. Connected through the link cable port, running with a whopping six AA batteries and retailing for the relatively high price of $60 upon release in 1998, the device uses thermal paper just like your receipt at the grocery store. Just like we discussed earlier with the camera, Nintendo knew they had to compensate for their bargain bin technology, so they wisely included thermal paper with a sticking back. This turned bad pictures into collectable pictures. You could stick your pictures in a book, collect pictures of different plants or animals, stick pictures of people on their books, etc. Selling paper with a sticky back was a genius idea to compensate for a poor printing quality; and the printing quality was indeed bad. No one goes to a thermal printer for a beautiful, detailed print. It’s a cheap way to get something on paper fast. It will work fine for fun prints to share in the moment, but you’re not going to preserve your pictures long-term with those prints. Just like your receipts the prints fade with time. So if you have any old printed pictures from way back, they’ll be very faded now, due to the thermal paper technology.

The Game Boy Printer enjoyed a life outside its release with the Game Boy Camera. A few games included the ability to print some stuff; banners, high scores, medals. Pokémon Yellow allowed you to print the content of your PC boxes for example, providing potential relief from all the box shuffling needed to manage your captured Pokémons. When I look at an exhaustive list of what can be printed, I find nothing impressive. Add the high price of the printer coupled with its large appetite for batteries and I feel like anyone who bought the printer was disappointed by its usage outside of Game Boy Camera. I didn’t buy it, and still do not own one; when I bought my Game Boy Camera, I did so for $20, a year after its release in the fall of 1999. I skipped the printer, which still retailed for its full price somehow. I don’t feel like I’m missing anything, especially since the Game Boy Printer is basically a repurposed receipt printer mechanism.

Accessing Your Pictures

If you’re like me, you own a Game Boy Camera with pictures that are decades old at this point. You might even have pictures that you consider valuable stuck on there. My sister had taken pictures of our family dog when he was a puppy. I wanted a way to extract them and get copies on my Mac. Having already explained how a Game Boy Printer is a poor fit for preservation, other options were needed.

Five or ten years ago, limited options existed but we now have a plethora of methods to extract pictures from a Game Boy, from the handmade low-run device like the BitBoy to the exquisite FPGA high-quality device like the Analogue Pocket. You also have the Epilogue GB Operator a cartridge port you somehow plug into your computer to play those games, and something like the Game Boy Camera Fast Wifi Adapter a project you assemble yourself using a bunch of parts that you fit inside a 3D printed case. Basically it’s a GBxCart RW coupled with a Raspberry Pi Zero. There are even more options if you want to do a bit of research. To solve the problem for me, I used something I already owned. Since I’m cheap, and didn’t want to spend money on a bespoke solution I’ll use once, I decided to use the little Arduino board I already own to transfer my pictures. This meant cutting up a Game Boy link cable and identifying each wire with continuity. Not the easiest thing, but it was a reasonable task for an amateur tinkerer like me. I was able to adequately mark the required wires, make new ends (always be sure to plug the ground wire in the right spot) and follow the instructions to load the software correctly and extract the data from the serial monitor. It was immediately successful, with my only issue being the extremely crappy software for the Arduino IDE. They should be ashamed of how many interface bugs they have in their software. Anyway, I encourage you to get your pictures extracted if you have any of sentimental value. That cell battery in there won’t last forever.

Never the Smallest

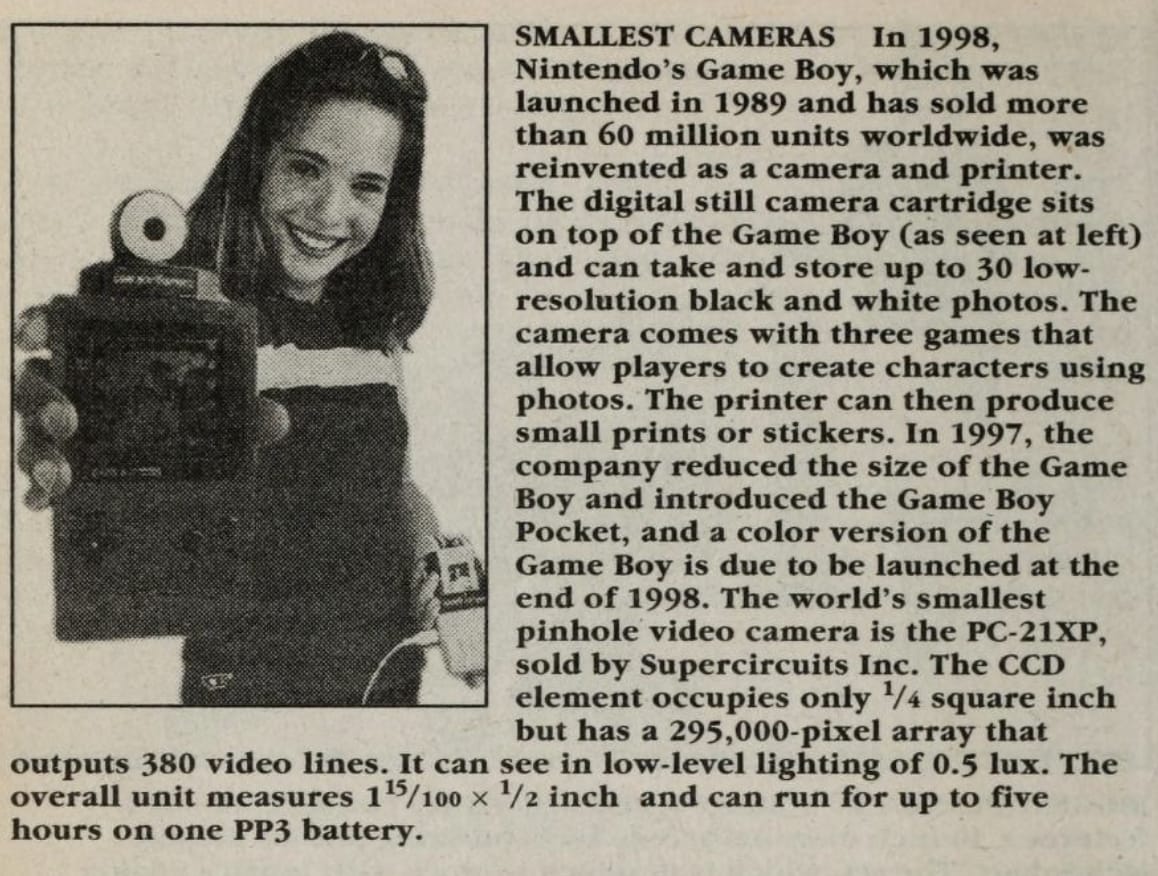

I had read on Wikipedia that the 1999 edition of the Guinness Book of World Records deemed the Game Boy Camera the world’s smallest digital camera. I wanted to read this mention in Guinness directly, so I headed to the Internet Archive’s controversial book rental system to read the 1999 Guinness book. Here is the paragraph talking about the Game Boy Camera on page 294.

SMALLEST CAMERAS In 1998, Nintendo’s Game Boy, which was launched in 1989 and has sold more than 60 million units worldwide, was reinvented as a camera and printer. The digital still camera cartridge sits on top of the Game Boy (as seen at left) and can take and store up to 30 low-resolution black and white photos. The camera comes with three games that allow players to create characters using photos. The printer can then produce small prints or stickers. In 1997, the company reduced the size of the Game Boy and introduced the Game Boy Pocket, and a color version of the Game Boy is due to be launched at the end of 1998. The world’s smallest pinhole video camera is the PC-21XP, sold by Supercircuits Inc. The CCD element occupies only ¼ square inch but has a 295,000-pixel array that outputs 380 video lines. It can see in low-level lighting of 0.5 lux. The overall unit measures 115/100 × ½ inch and can run for up to five hours on one PP3 battery.

As you can see reading it, no mention is made of the Game Boy being the smallest of anything. You could perhaps read the description of the PC-21XP described as the world’s smallest pinhole video camera and think this applies to the Game Boy Camera. Unfortunately, the cartridge does not use a PC-21XP as its camera element. The camera uses a Mitsubishi M64282FP CMOS image sensor. So the book actually mixes two subject matters into one paragraph, and uses the confusing title Smallest Cameras. You could still read the paragraph and believe they simply did not directly write it, but the book actually names the Panasonic NV-DCF2B as the world’s smallest digital camera with a viewfinder just one page before. Reading the rest of the section on gadgets, it’s clear the paragraph is just meant to describe an interesting device. Two other devices which are not record-holders of anything are later mentioned in the same manner as the Game Boy Camera: a lollipop that plays music and a 360-degree television.

To be 100% sure, I contacted Guinness by email and they confirmed that the Game Boy Camera was never assigned any record. Case closed: the Game Boy Camera was never the world’s smallest anything. Any mention of a Guinness record, even when properly transcribing what is written by Guinness, should be questioned. It’s always been a book of factoids and weird trivia instead of a serious reference. Reading anything related to technology feels like you’re reading a collection of statements pulled straight out from press releases. How can anyone validate the record for the most recyclable car beyond the car company’s own statement? Couple that with the broken relationship between the speed running community and Guinness, and it shows a company incapable of understanding video games. Case in point, Guinness removed Billy Mitchell’s gaming records the year after his cheating was revealed. So far so good, but they somehow reinstated those same records two years later, after he had been unequivocally proven to have lied about his achievements. He had already been banned from both serious Donkey Kong score-keeping organizations. This puts Guinness under a very bad light; they have no qualms crediting records to a cheater. They also assigned ultra-specific records to Tommy Tallarico in a clear example of their pay-for-play record scheme. I’m not going to mention Guinness ever again without some heavy research.

The wrong information about the Game Boy Camera record has been on Wikipedia since it was added by an anonymous contributor in June 2008. You can now find this fake fact mentioned in tons of articles online, on Wikia, probably in a bunch of books. Look at Digicam History and Digitalkameramuseum for example, two old websites cataloguing the pre-1999 history of digital cameras who both mention the non-existent record. I’ve emailed both to have them remove it, but I predict I will see this false information until I die.

Conclusion

When I was in high school, I would bring my Game Boy to play between classes or to show my closest friends the latest games I was playing. No one really gave a second thought that I brought my old Game Boy to school. When I ended up buying a Game Boy Camera, it felt natural to show it to my friends. I was in for a rude lesson. When I brought the Game Boy Camera to school, it immediately caused a ruckus. When they discovered that my Game Boy could take a picture and immediately show it on its screen, my whole class congregated around my Game Boy, rudely taking it from me. People were suddenly taking selfies, way before the concept was attached to a word, and fighting over who was going to take a picture next. It turned into a pandemonium of excited teenagers screaming at one another to have the camera. A classmate even shoved the camera down her shirt to take a picture of her cleavage. With hindsight, I saw in those five minutes the natural excitement for all the social sharing of pictures we now have in the era of the smartphone. I saw selfies before the word had left Australia, the pouty lips people make when taking those selfies, the incessant sharing of inane pictures you now see on stuff like Snapchat, and even the burgeoning concept of sexting, all with my Game Boy!

That’s how starved for cameras my generation was.

I vividly remember not being allowed to touch the family camera; I was told I would probably break it. Everyone I knew had more or less the same experience, where a camera was an expensive tool reserved for adults. Remember, it cost money every time you pressed the shutter button. You also had to send the film to be developed, which meant that a stranger looked at every picture you took. It was common to talk about the weirdness of technicians looking at your pictures. That put social pressure on what you could shoot. I totally understand that classmate realizing she could snap her cleavage with abandon now that she knew no stranger would see the picture. The appeal of a cheap camera you could play around with without worry was hella powerful.

With class about to start, the teacher getting angsty, and me wanting to get my beloved Game Boy back, I ended up in a tussle and pushed a classmate trying to get it back. Falling down, he dropped his glasses and they broke on the ground. That’s right kids; Game Boy Camera led me to violence and got me in trouble with my school principal! I was so ashamed I hid the whole thing from my parents and paid for the repair of his glasses with my own money.

I wouldn’t blame you if you never want to read anything from me again due to this Game Boy transgression.

This article was first published on the .

This article was last modified on the .