Donkey Kong Land 2

- North American release in September 1996

- Japanese release in November 1996

- European release in November 1996

- European release in 1996

- Australian release in 1996

- North American release in 1997

- North American release in 1998

- North American release in November 1999

- Player’s Choice Re-release

- Japanese release in March 2000

- Developed by Rare Ltd.

Ape Escape

My article on Donkey Kong Land is by far my most popular. It’s the one that has received the most feedback; from book reviews on Amazon, from Reddit’s /r/gameboy, from talking to my friends. With that in mind, I should feel a certain responsibility discussing Donkey Kong Land 2. Since they barely changed anything, I don’t. it’s just talking about the same core mistakes all over again.

With the first game, I had decades of experience to share; I owned the game has a kid. This time, I bought the game as an adult, specifically for this project. Since I have never played the game before, it means my opinions are fresh. The game features only minuscule improvements on the issues I had with the first game, so I am disappointed to say I do not like this sequel. It stings particularly because this game tries to reproduce Donkey Kong Country 2: Diddy’s Kong Quest for the Game Boy, and I simply adore Donkey Kong Country 2. I have fond memories of playing the game with my best friend from primary school, slowly inching our way, level by level, through this difficult Super Nintendo classic. Donkey Kong Land 2 attempts to ape this seminal game and fails miserably. At least the first Land game had original levels. Essentially, we’re faced here with the harsh fact that a bad adaptation of a great game is worse than a bad but original work.

Slightly Better on the Eyes

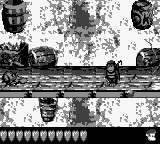

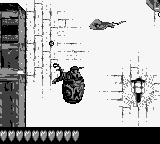

The biggest issue with the first Donkey Kong Land is its inscrutable backgrounds that make everything blurry. The developers of Donkey Kong Land 2 thought so too; the second game has somewhat cleaner backgrounds.

They evidently tried to alleviate the problem by using more whitespace but I think they were trying to improve a fundamentally flawed concept. There is no way to make 3D designs work flawlessly on the original Game Boy screen, no matter how much whitespace you’re leaving in the background. They did not fully commit to the improvements; you still have many decorative elements that crush visibility throughout the game. You can better discern the position of the dark blobs that populate the screen, but you’ll have a hard time figuring out what those blobs are supposed to be.

Is this a background element or an enemy? It threw what looks like a barrel, so I guess it’s an enemy? Oh, it wasn’t a barrel, it was a cannonball so now I’m dead. Why don’t I play some Kirby’s Dream Land 2 instead of this crap?

You need the clean lines of hand-drawn pixel art to give you a game you’ll be able to see without issues. Since the whole marketing angle of the Donkey Kong Country series was its use of 3D graphics, they chose to use the same underlying technique on Game Boy. To hell with the game’s quality.

Pocket Reinvention

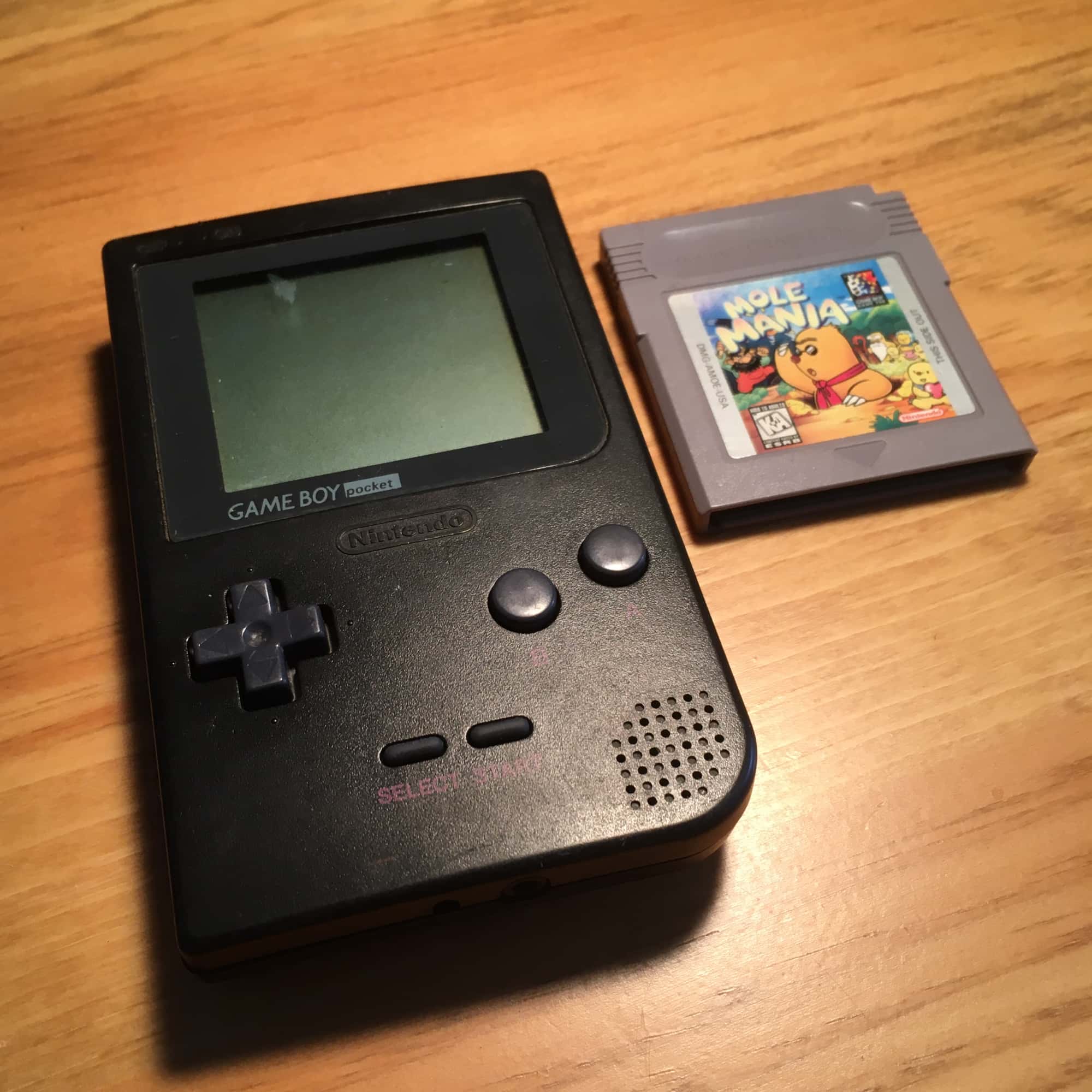

Just like Donkey Kong Land was released to coincide with the arrival of the Super Game Boy on store shelves, Donkey Kong Land 2 was released on the same day as the Game Boy Pocket. If we are supposed to understand that this game was made with the Game Boy Pocket in mind, I guess it solves its more egregious graphical issues, but we still must acknowledge all the poor players who did not own a Game Boy Pocket to play this bad game. I had to contend with my trusty grey brick until I bought a Game Boy Color in 2000, and I was not alone. For seven years the Game Boy had been sold to most everyone who wanted a Game Boy when the Game Boy Pocket was introduced in 1996. The Pocket did not sell particularly well nor change the Game Boy market significantly. It also raised the sale price of the Game Boy by $10 USD upon release. How come Nintendo improved their initial design only by 1996? Because during four of those seven years, Gunpei Yokoi and R&D1 were busy working on the Virtual Boy. Once they finally abandoned it on the market in 1995, Yokoi finally tasked his team with building a better Game Boy.

That the Game Boy Pocket came as the amends for the sins of Virtual Boy makes sense. Since their previous creation was too much of an overreach, they went in the opposite direction and the Game Boy Pocket is the safest redesign possible. Its marquee feature is the improved display, finally breaking from the shackles of the iconic green screen. The Game Boy Pocket still uses a super-twisted nematic LCD with all its faults, but it is much improved, with far less ghosting and true shades of grey. They also made the screen slightly bigger in physical size while keeping the same resolution. The screen has no light source, but that was still par for the course for a device sold for $70 USD in 1996. The overall device size is smaller, with a fresh, timeless design.

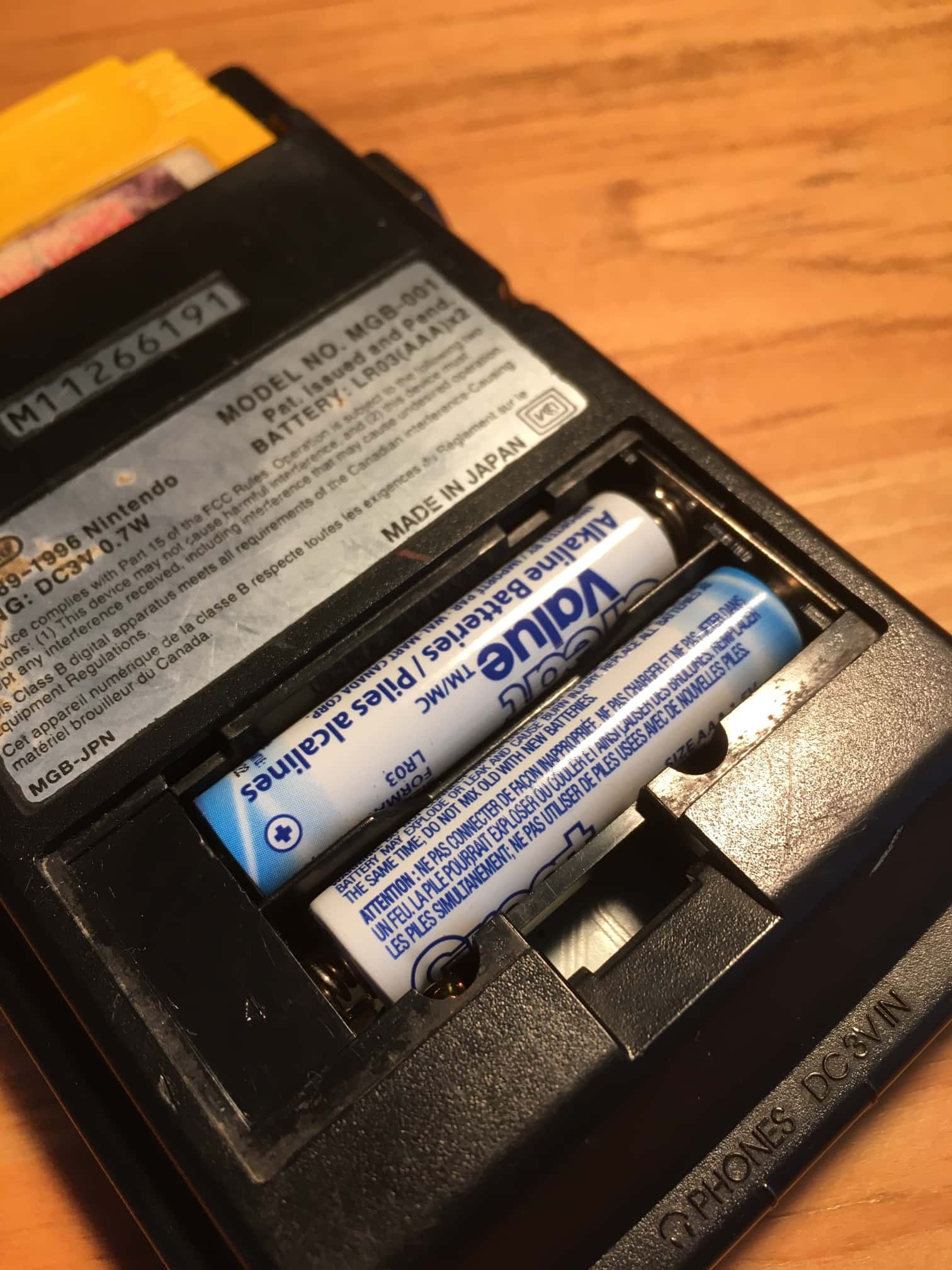

They were also able to only require two batteries, since between the release of the DMG in 1989 and the Pocket in 1996, a small revolution happened in the world of consumer electronics: the move from 5 V to 3 V. The crew at Nintendo R&D1 were able to make the Pocket work with 3 V, meaning that instead of the four batteries needed to reach 5 V (a single AA battery provides a nominal 1.5 V), you only needed two batteries to reach 3 V. On the negative side, they chose to use AAA batteries, which dropped the battery life of the Pocket to the 10-hour mark, while the original DMG usually gave you 20 hours of gameplay with its AAs. No other Game Boy would ever use the diminutive AAA batteries again, and they would all offer more than 10 hours of battery life. All that to say that Donkey Kong Land 2 had at its disposal a device better suited for its visuals, but it still doesn’t make the game good.

Bad as a Portable Donkey Kong Country 2

You might be tempted to say: “Pierre-Luc, the first game was just a bizarre adaptation with original levels and areas. This time, they just ported Donkey Kong Country 2, so it must be good?” Before I tell you that you’re unfortunately wrong, I wish to define one word in your sentence, the word port. What is a port? Let’s define it by peeling the onion of DKL2.

The first layer, the marketing of the game, is indeed different from the Super Nintendo game. It has a different name, uses different images to promote itself. But it is irrelevant, since a port is not defined by its appearance outside the software that makes the game. We already established previously that Heroes of Might & Magic on Game Boy Color was not a port simply because it reused the same name.

The second layer, once the game is played, is the world map. It is strikingly similar to the original game. The second and third areas have been merged, inside each area you have small changes here and there, and the world map is for some reason mirrored, but we do not have something that would disqualify this game as a port.

On the third layer, once you play a level, the game style and controls are nearly the same. We have a platform game with the same overall controls, with some concessions made for the four-button difference between both consoles. Gone is the team-up move, which allowed a Kong to stand on the shoulder of the other one to reach higher platforms.

It’s at the fourth layer, the level layouts, that we reach the unequivocal truth that we are not playing a port, since every single level is different from the SNES game. They usually have the same theme as their SNES versions. One level is about using barrels to navigate vines, another level features jumping on reeds in a swamp. But every level is different; they’re dumbed-down echoes of the SNES levels. They’re meant to confuse you by looking like the Super Nintendo original levels. This highlights a fundamental truth that applies to so many Game Boy games: unless the original environmental resolution is maintained, a game cannot be a port. Puzzle games like Tetris, Mario’s Picross or Dr. Mario require fewer pixels to function than the Game Boy has, so they can be ports. Turn-based games like Game Boy Wars and Dragon Warrior I & II can scroll and offer menus to display the same amount of data, so they can be ports (the Game Boy Wars games were original titles but it’s just an example). Point-and-click adventure games like Shadowgate redraw their environments, but change nothing about their original structure so they also work. Super Mario Bros. Deluxe is indeed a port, since they didn’t change the levels or Mario’s jumping to fit within the screen. Finally, a great example is DuckTales. Most mentions of the Game Boy version call it a port, but it is not. It looks awfully similar to the NES game, but a lot has been changed in the levels to make the game possible on the portable system. This is the same with DKL2. Most people will call it a port, but it is definitely not a port because of the irreconcilable level differences.

So now that we’ve established that it is not a straight port, but a reimagining of DKC2, I can tell you the decisions they made to reimagine the classic SNES game are horrible. I won’t go into too much detail, but suffice it to say they made an easier, shorter and way less interesting game. Levels in DKC2 have this delicious forward momentum. You always want to unfold the next challenge. For example, in Kannon’s Klaim, the second level of the second world is filled with Krocs that shoot barrels or cannonballs. You’re climbing up the mine shaft, and you’re constantly bombarded by new challenges using those same enemies. It’s fun to discover the designers’ next idea. On Game Boy, they’ve all been taken out. The adaptation of this level is just a repetition of Auto Fire Barrels over and over until the end of the level where you have one crocodile with a cannon. They only put one signature enemy of the level! I think they removed those enemies because they were too hard to see on the Game Boy screen, which meant they took out all the fun out of the level.

The whole game is like that. The first world on SNES, the pirate boat, is this fun, easy world with lots of secrets hidden all over the place. They took out the exploration and fun secrets on Game Boy. The third world is this swamp with interesting jumping challenges on SNES. The levels that survived the transition to Game Boy are just boring.

The most exciting section of Donkey Kong Country 2 is Kremland, a deadly amusement park interspersed with beehives. It’s this tough area with most levels featuring exciting new play styles. There are two similar roller coaster levels and they went so far has to give them two different control styles; one has the Kong jump from the cart and the other has the cart itself jump. On the other hand, the Game Boy’s Kremland area is just boring. I stopped playing as I reached the Kremland area on Game Boy. I cannot believe that the developers at Rare suddenly became good at porting their own game. Their first two levels were simply too bad for me to warrant any more of my time.

Once Again Saddled With a Terrible Camera

My limited time with the game allowed me to confirm that the camera is still problematic. The game features the same twitchy camera that I hated so much with the first game. My camera experimentation also allowed me to discover another issue I have with this game. The second level of DKC2, Mainbrace Mayhem, is actually a personal favourite. It’s set on the pirate ship’s sails and I love it because you never get confused about where to go next in this vertical level that you navigate in a seesaw pattern. It does this by locking the camera’s vertical scrolling; you can’t make it scroll any higher by jumping when there is another section of the level above you. You can sometimes break that mechanism by jumping much higher than you normally would, but it is surprisingly effective at guiding you towards your destination without confusing you. It’s not perfect, but it works surprisingly well.

DKL2 works the same way, but the level structure is more cramped, so you often jump and see level elements to the sides. You start wondering where you are supposed to go, and can easily skip whole sections of the level simply because you saw a space much later in the level you could reach. It’s great if you want to quickly get through a level, but terrible in a design sense. This is a common occurrence with this game: it tries to ape the SNES game but does it in a bad way which causes confusion.

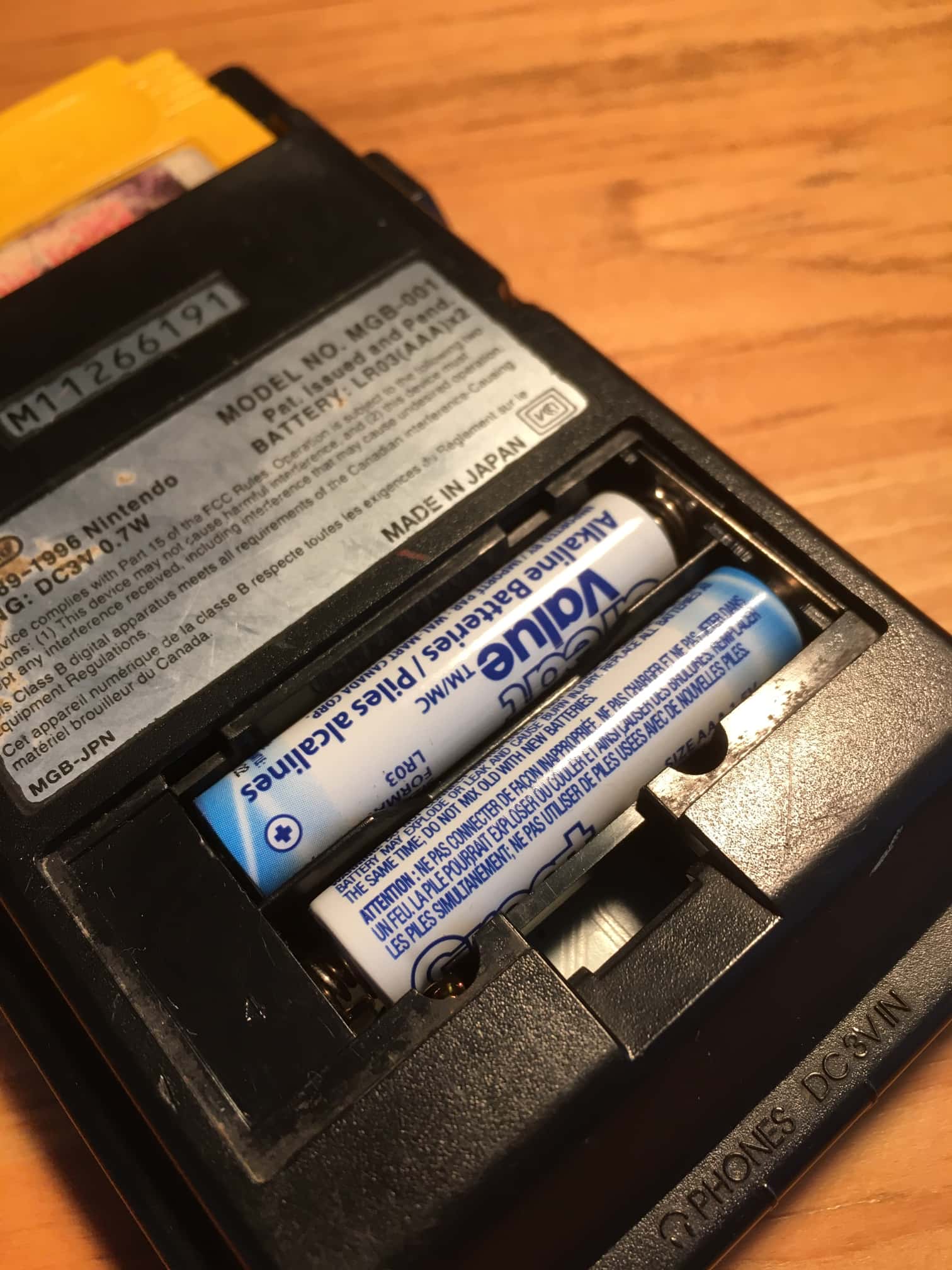

Saving & Batteries

Let’s take a final moment to discuss something tangentially related to this game: batteries. My cartridge of Donkey Kong Land 2 had a dead battery, so I had to change it. The way to know a battery is dead is your save gets deleted the second you turn off your Game Boy.

Saves on cartridge games work with a watch battery hidden inside the cartridge that keeps a small dedicated section of RAM powered without interruption for decades. If this small RAM section is without electricity, your saves are gone. It sounds crazy but it works. The battery is not getting recharged while the console is powered on either; watch batteries are non-rechargeable. It just works for decades without issues. It can stay powered on for so long because a watch battery can last a very long time if it only needs to power some small circuitry without a display.

If you buy original Game Boy cartridges in this day and age, you will eventually encounter a cartridge that no longer keeps your saves. However, if you decide to change a game’s battery yourself, here are some pieces of advice:

- Buy the specific screwdriver you need to open a Game Boy cart. Do not fall for that melted pen trick, it’s a terrible idea that always ends in a mess.

- You don’t necessarily need to de-solder the battery connectors. I use a box cutter and patience to cut the very little bit of solder on the battery.

- Don’t hesitate to use a slightly bigger battery. I use CR2032 batteries since they’re so easy to find, and they also help with my final tip.

- Use electric tape to hold the battery snugly between the original connectors. Since I use bigger batteries, the cartridge’s plastic housing also squeezes the battery in place.

However, don’t repeat my rookie mistake; don’t put the battery on backward and then think the cartridge itself is broken. I had done that and was convinced my cartridge was screwed. I finally realized my mistake after an embarrassing amount of time.

Conclusion

I feel like I talked about everything around Donkey Kong Land 2 instead of talking about this forsaken game. Have you read my last paragraph? I talked about batteries! Jeez.

I did all that for good reasons, since there is not a lot to talk about. The game is slightly better than the first one, but it still is fundamentally broken. The people at Rare could have easily redesigned the core concept, but they instead just made the same mistakes again. They probably believed that adapting SNES levels and lowering the number of details in the backgrounds would be enough to improve their concept. They were wrong.

I guess it proves that the developers at Rare never lost their roots as developers of flawed games. They made interesting games before Donkey Kong Country when they were originally Ultimate Play the Game and afterwards as Rare. Their games usually had some sort of fatal flaw that made them impossible to love. Battletoads like most of their games was way too hard. A Nightmare on Elm Street was too complicated for its own sake. Wizards & Warriors had floaty controls ill-suited for the levels in the game. When they started collaborating directly with Nintendo, however, they started making flawless titles. They also severely slowed down and stopped releasing a dizzying number of games. They still had it in them to make a bunch of clunkers, it seems.

This article was first published on the .

This article was last modified on the .